The Mayors Challenge—and the skills-building that comes with participating

The Bloomberg Philanthropies Mayors Challenge asks city leaders to put forward bold ideas for solving their toughest problems. Winning cities receive up to $1 million to implement their plans, along with expert coaching and technical support. The latest round of the competition is open to all cities globally with populations greater than 100,000.

The Mayors Challenge isn’t just about big ideas, however. It’s also a process, one that helps cities build their innovation muscles by giving mayors and their staffs a chance to try new ways of problem solving that put residents in the center of solutions. Along the way, teams learn skills they can apply to other issues they’re working on. It’s a big reason why even cities that don’t get the prize money still come out winners.

Here are four of the skills city leaders learned in the last Mayors Challenge:

Defining a problem

One of the toughest things for city leaders to do is identify exactly what aspects of a problem they want to address. That’s because so many of the challenges they face—say, tackling the impacts of COVID-19 or building an equitable economy—are big, complicated, and urgent. Another difficulty: Leaders sometimes come to the table with assumptions that may not be accurate, or with pre-baked notions about what solutions are needed.

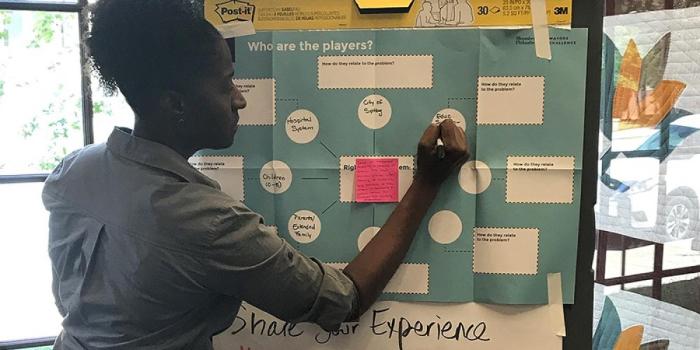

The Mayors Challenge prompts city leaders to start with questions rather than answers. They learn to use data to understand the scale of the problem and engage community stakeholders to identify different dimensions and root causes of the problem. Often, this process leads cities to shift or narrow their focus, said Sania Salman, an innovation and design expert who led more than a dozen “idea accelerator” workshops with U.S. cities as part of the 2018 Mayors Challenge. “The most fascinating part,” Salman said, is “the way the curriculum showed city leaders how to take something that might, at first, be a broad, urgent problem and then whittle it down into a much more concrete and targeted aspect of that problem.”

Read more:

On the ground in 300-plus U.S. city halls

Report on the first phase of the 2018 U.S. Mayors Challenge

Co-creating ideas with residents

City leaders design solutions with—not for—their residents. That’s a critical idea in the Mayors Challenge. An expectation of deep engagement with residents is woven into every step, from identifying the problems cities are working on to developing, testing, and implementing solutions.

In the last Mayors Challenge, city leaders went beyond the usual town-hall meeting to engage with residents on social media, in one-on-one interviews, and in group settings like focus groups and facilitated workshops. In New Rochelle, N.Y., they set up at a Saturday-morning farmers market to get feedback from residents. In Los Angeles, they worked directly with residents experiencing homelessness to develop a housing solution involving small backyard dwellings.

As Results for America’s Jennifer Park, who coached a number of cities through the early stages of the last Mayors Challenge, put it, “Cities are most successful...when they bring the right folks to the table—and this includes both the naysayers and people directly affected by the problem.

Read more:

How citizen input supercharged three energy-saving ideas

Using virtual reality to engage residents

Testing, learning, and adapting

In the last Mayors Challenge, city leaders learned how to use a tool that was new to many of them: prototyping. By breaking down their solutions into small pieces that could be tested out with residents, they were able to quickly gain insights they could use to refine and improve their ideas.

For example, Philadelphia officials had an idea to create a juvenile justice hub for young people who get arrested, as a more humane and “trauma-informed” alternative to adult jails. They prototyped the idea by building a mock-up of the space, complete with comfortable furniture and plants, and having teenagers, police officers, and social workers role-play their interactions. Through multiple rounds of play-acting, they were able to fine-tune how the hub would work, long before investing much time or money into the idea.

What cities learned is that prototyping reduces risk and saves money, said Stephanie Wade of Bloomberg Philanthropies. “It helps you get to the right answer faster and cheaper,” she added, “so that by the time you’re investing a large amount of capital into a new program or policy with far-reaching implications, you know you’ll have the impact you hope to have.”

Read more:

The Mayors Challenge: Unleashing the power of public prototyping

Explainer: What is prototyping?

Pivoting with purpose

Sometimes, testing an idea with residents helps city leaders to recognize that they are on the wrong track with an idea. While that can be a difficult conclusion to reach, they’ve also found through the Mayors Challenge that it’s OK to take what they’ve learned and pivot in a different direction.

That’s what happened in Charleston, S.C. In the last Mayors Challenge, the city pursued the idea of building an app to help residents navigate the increasingly frequent menace of street flooding. At first, city leaders were certain that residents would want to see live video feeds of flooding as part of this offering. But when they tested the idea with users, hardly anybody said they wanted video. Instead, they wanted maps showing where streets were flooded and directions to get around the waters. City leaders went back and reworked their idea substantially.

“Don’t ever do anything like this unless you’re going to spend the time engaging the community, finding out what’s important to them, and then building it with them,” said Mark Wilbert, the city’s chief resilience officer. “At times you think you know what the people want. But there’s great value in really interacting with them, listening to them, and responding to them.”

Read more:

How residents can help cities stand up to extreme weather

Pivoting with purpose: How to change course and keep innovating