Philadelphia’s ‘trauma-informed’ approach to youth justice gives kids a lift

“Hope” is not a word typically associated with juvenile arrests. Dr. Meagan Corrado thinks it should be.

Corrado is a licensed clinical social worker who specializes in trauma treatment for children and teenagers. She’s also an adviser to a Philadelphia initiative aimed at changing the ways the criminal justice system works with young people — a prize-winning idea in the 2018 Bloomberg Philanthropies Mayors Challenge. Launched in 2012 by Mike Bloomberg, the Mayors Challenge is an ideas competition inspired by Bloomberg’s experience as a three-term mayor of New York City and funded by his pioneering philanthropic effort to spur and support a public-sector innovation in other cities around the world.

Corrado’s goal in Philadelphia is to build a “trauma-informed” approach to how everyone from police to social workers interact with youth in the arrest process. Historically, that’s not been a high priority. Most youth, no matter the level of their charged offense, have been handled more or less like adults — put in the same concrete cells, sometimes for many hours, without much communication about whether a parent or guardian has been notified or what to expect. This is a moment when the system begins writing many of these children off, Corrado says. “I’ve had people tell me: ‘Good luck getting anything out of this one.’ Or: ‘They’ll never change.’”

That’s where hope comes in. “When we treat people as if there is no hope for them, they feel that,” Corrado says. “But when we treat people as if there is opportunity for change and growth, they feel that, too. It helps the individuals feel a little bit more hopeful and optimistic about the future they can build for themselves.”

Hope is one of four principles in Philadelphia’s trauma-informed approach. The model is part of a national push to create best practices for how cities assess youth after an arrest. It’s also a model that Corrado, who teaches at Bryn Mawr College, believes cities could put to work outside of law enforcement to inform homeless services, courts, fire and rescue, or virtually any interaction where residents must pay taxes or fines.

And it’s especially relevant during a year when so many people are experiencing new traumas and resurfacing old ones, as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and a national reckoning over racial injustice. “A trauma-informed approach,” she says, “could be used in every facet of local government.”\

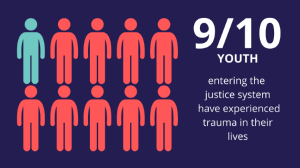

But what does “trauma-informed” mean? In Philadelphia’s project, it means dealing directly but sensitively with a troubling fact: About nine in ten youth entering the justice system have experienced trauma in their lives — such as physical abuse, sexual abuse, or violence — and often several of them. The idea is to identify ways to help these young people feel safe and supported on a path to recovery, and to make sure they’re not re-traumatized by the stress of a police encounter or a degrading arrest procedure.

Eventually, Philadelphia expects to build a separate intake center for juveniles, to create a more child-friendly environment than is typically found at police stations. There, youth will interact with social workers who are trained to support youth in times of crisis, in a setting that young people played an active role in prototyping and testing.

[Read: Philadelphia prototypes its concept for a juvenile justice hub]

The idea for this “Juvenile Assessment Center” initially came from two Philadelphia police officers who thought there must be a better path for young people entering the justice system. Until it can be built, Philadelphia’s trauma-informed approach will happen mostly through training police officers using a curriculum that Corrado is developing. That training will help officers understand how trauma impacts youth development and integrate that knowledge into their interactions with young people.

All of it is guided by four principles which Corrado and her Philadelphia colleagues curated from a growing literature on trauma-informed approaches. The Philadelphia principles are:

Safety. People who’ve been through trauma have had their basic sense of safety compromised, Corrado says, and that can result in agitation, anxiety, or aggression when put under the stress of a police encounter. “It’s important to create an environment where the youth are physically, emotionally, and psychologically safe,” she says.

Respect. Whether because of their age or the offenses they’ve been charged with, youth often aren’t shown much respect when interacting with the juvenile justice system, Corrado says. That has to change. “Showing respect to youth means staff use healthy communication skills, are responsive to basic needs, and implement deescalation strategies when youth are feeling stressed out and tense,” Corrado says.

Communication. When young people experience the stress of an arrest stacked on top of an earlier trauma, it can be difficult for them to take in what’s happening, Corrado says. That makes clear communication critical. “Whenever possible, staff should communicate with youth about each step in the arrest process,” she says. “Letting youth know what’s happening can reduce anxiety and acting-out behaviors. Communication should be simple, clear, and direct. Sometimes, staff may need to repeat information multiple times. This is normal. When their brain and body are in a state of stress, it can be difficult for youth to process and retain new information.”

Hope. In juvenile settings, Corrado says, it’s important to remember that youth are not simply the mistakes they may have made before getting arrested. “Instead of defining people by their worst moment, we can support them in identifying their strengths and sources of resilience, so that they know they can be so much more than that mistake,” Corrado says. “Neuroscience tells us that every person has the ability to change destructive patterns and create healthier patterns in the future. This knowledge should impact the tone and attitude with which staff approach their interactions with youth.”

Corrado believes that these principles should apply not only to how city staff interact with youth but with how staff deal with each other. In this way, she says, the benefits of trauma-informed approaches can trickle down into the culture and morale of first responders and other frontline local workers who deal daily with stressful situations and carry traumas of their own.

“The lesson for local governments is that a trauma-informed approach is not just for therapists,” Corrado says. “It’s for all of us. Most of us have encountered and experienced at least one trauma throughout the course of our lives. And whether we admit it or not, those traumas have an impact on us. And we have to take a systemic approach in order to address it.”

Photo courtesy of Shutterstock