How virtual reality is helping create real change in cities

Amelia Winger-Bearskin has been watching a lot of video lately — footage of public planning meetings in New Rochelle, N.Y., where she runs a lab for interactive visual arts. And she’s started to notice a few patterns: Most meetings are attended by the same group of citizens; they get only a minute or two to speak their minds about proposed developments; and their comments are almost always negative.

There’s lots wrong with this, Winger-Bearskin said — from the lack of useful feedback to the inconvenient meeting times that make it difficult for a broader mix of residents to have their say. But the biggest problem is that development proposals are almost fully cooked before they even make it to the public meeting. “By this point, it’s already pretty late in the game,” she said. “How much is the city or a developer really going to weigh public feedback this late in the process?”

Winger-Bearskin is leading an effort in New Rochelle to make citizens more integral in the development process. And she and a team of city and business leaders are using virtual reality to do so. They believe that the same technologies powering today’s cutting-edge video games can also give residents an immersive perspective on proposed developments.

There’s profound potential here, Winger-Bearskin said. With development booming in this New York City suburb of 75,000, the vision is to have citizens proactively shape the change going on around them, rather than simply reacting as it happens. “Developers and architects already have access to really advanced super-sexy visualization tools,” she said. “But if the mayor’s office has that same kind of tool — along with the city planning team, the head of development, and citizens — you can actually start getting citizens to co-design their city.”

[Get the latest innovation news from Bloomberg Cities! Subscribe to SPARK.]

New Rochelle is currently prototyping this idea as part of the Bloomberg Philanthropies Mayors Challenge. It’s one of 35 “Champion Cities” that received $100,000 to test out bold ideas for solving tough urban problems — and to adapt those ideas based on what they learn from all the testing. In October, four cities will win $1 million to implement their ideas; one will win $5 million.

In New Rochelle, a recent round of prototyping took place at a farmers market. About 60 people took a break from their shopping to try out three different immersive technologies. Each was intended to spark ideas about how to improve the same public park where the farmers market takes place.

At one station, citizens used an “augmented reality” app that allowed them to see on their smartphones what the park would look like with various new kinds of street furniture. At another station, they used Streetmix, an interactive desktop tool that lets users design their own street. A third station offered a full virtual-reality experience with goggles, allowing users to see versions of the park and respond what they did and didn’t like.

Citizens offered useful feedback right away. One person noted that there’s no recycling bins in the park, even though farmers market customers generate a lot of recyclable trash. A new bin is on its way. (New Rochelle is chronicling its prototyping experience on Medium here.)

“What we’re trying to do is think about how we can have a constant measurement of our citizens’ needs and wants,” Winger-Bearskin said, pointing to the Saturday-morning farmers market as a more accessible sort of venue than the public meetings she watched. “And you can get that feedback long before those final development decisions are made.”

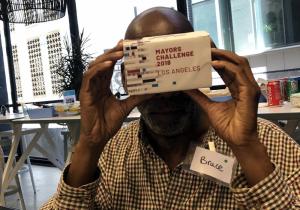

New Rochelle isn’t the only city where virtual reality has come into play during the testing phase of the Mayors Challenge. Los Angeles found a bare-bones version of the technology helpful in prototyping a proposal to tackle homelessness.

The idea is part of L.A.’s ongoing effort to address its housing shortage by encouraging homeowners to build backyard apartments or “granny flats.” Through the Mayors Challenge, L.A. is testing whether these tiny homes could be part of the solution to the city’s growing homelessness problem.

[Read: Prototyping city solutions and launching a revolution]

One assumption L.A. is testing is the notion that people would want to live in these houses in the first place. The L.A. team wanted to get feedback from people who had experienced homelessness, and when logistical and time constraints made that difficult, virtual reality was the solution.

Helen Rigg, a project manager with the city’s Innovation and Transformation Division, was already familiar with quick and easy ways of turning 360-degree smartphone photos into immersive experiences using a cardboard viewer — she does it with vacation photos. Why not try that with tiny houses? It wouldn’t be a full-on virtual reality experience with a headset, but it would get the job done.

“We didn’t want to intimidate people with the technology, so we tried to do it in as low-fidelity and approachable a way as possible,” she said. “That’s something we learned from prototyping —giving people something that doesn’t look totally finished helps them to give truer feedback.” They also paired the virtual experience with a 3D paper model of the backyard homes in relation to other houses, as a way of connecting it to something that felt tangible.

And the feedback was indeed useful. As they looked through the cardboard viewer, several people said they would look forward to making such a space their own. Others noted that the space might be too small for them — they wondered if it would be large enough to have friends over, or whether it would be isolating to live in someone’s backyard. “It’s not for everyone,” Rigg said.

Likewise, virtual reality won’t be a solution for everyone. “You’ve got to understand who your audience is and what purpose you’re trying to achieve,” Rigg said. “The reason we used it is because we had a need and it seemed like a really good way to fill that needed. We wanted people to give us feedback on something and have them experience it in the most effective way we could do that within our limited time and budget.”