Prototyping city solutions and launching a revolution

Take an innovative idea (for improving school readiness, slashing energy bills, or fighting drug addiction, for example). Add a dash of hard work, creativity, and — of all things — art supplies. And come away with a stronger sense of how to tackle some of the most critical issues facing U.S. cities today.

That was the challenge teams from 35 U.S. cities accepted earlier this week as they came together in New York City for an unprecedented experiment in prototyping. Armed with scissors, tape, and Sharpies, groups of four city hall staff and their partners built rough representations of smartphone apps, communications materials, and even a car. Then, using their imagination, they tested out each other’s prototypes, offered quick feedback, and revised their work.

These quick-and-dirty trials were the first of many these cities are undergoing over the next six months. As Champion Cities in this year’s Mayors Challenge, they’re each receiving up to $100,000 from Bloomberg Philanthropies to test their proposal for solving one of the most pressing concerns cities are facing today. When this testing phase wraps up, one city will win a grand prize of $5 million to execute its idea, while four others each will win $1 million. Winners will be announced in October.

While their prototypes will get more sophisticated over the coming months, imperfection was the point at this week’s Ideas Camp — to get a jump start on testing, learning, and adapting their ideas. Even simple “low-fidelity” mockups made of cardboard, pipe cleaners, and stickers, can give residents something concrete to interact with that helps them understand the real-life implications of an idea so they can provide helpful feedback for improvement before city hall spends money developing it.

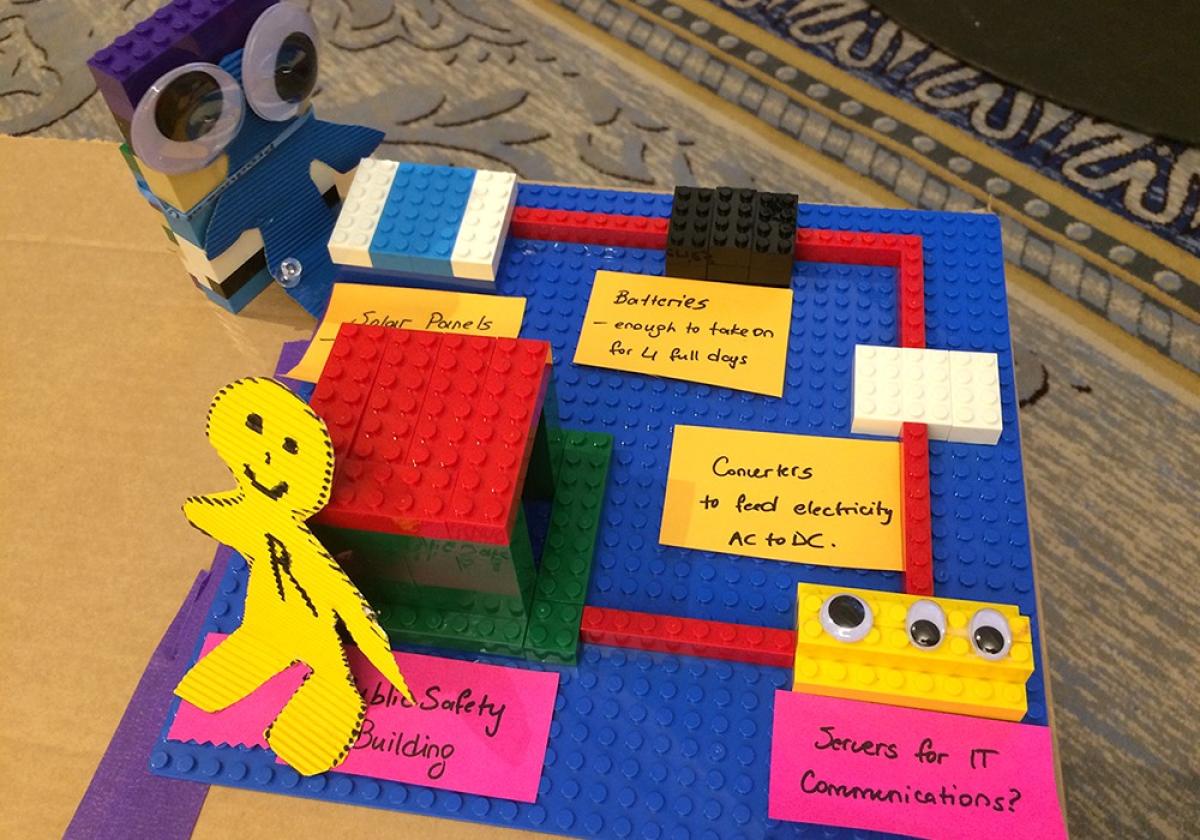

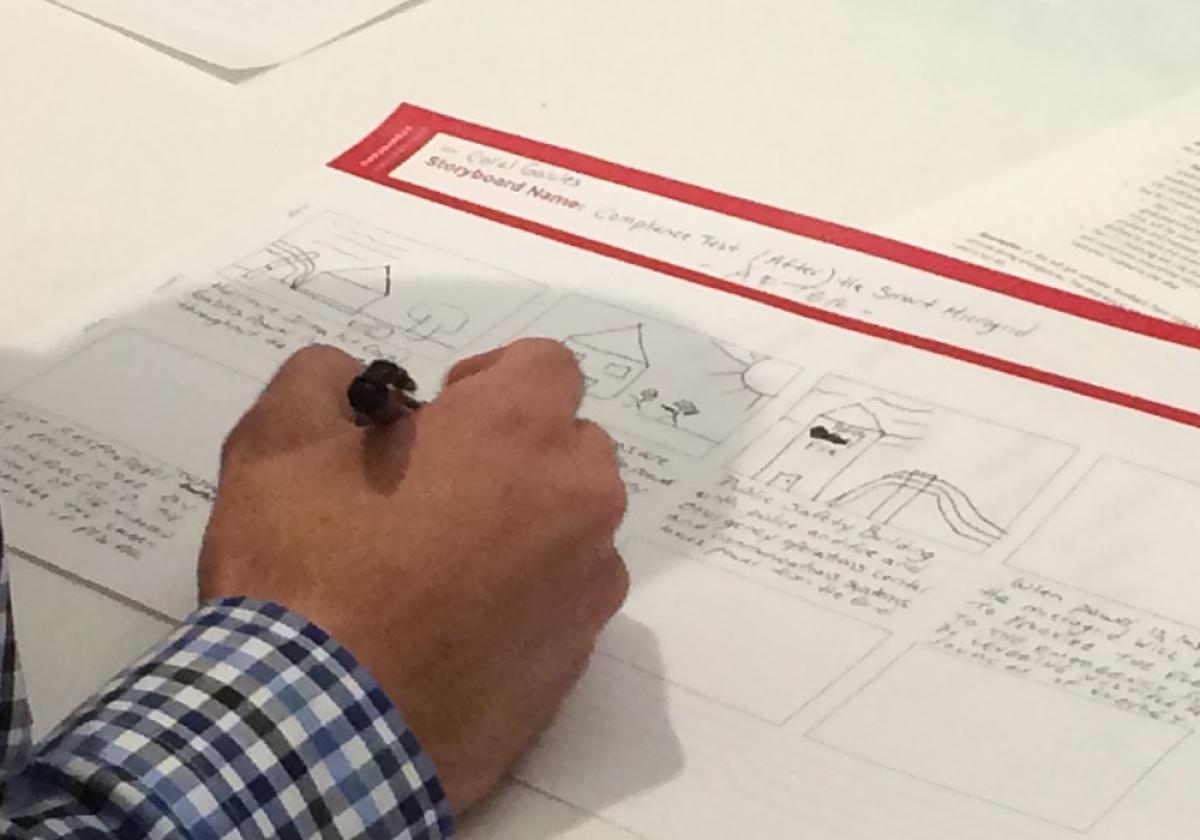

It took only a half hour for the team from Coral Gables, Fla., to create a LEGO version of the solar-powered “microgrid” they hope will power emergency services during disasters; the team from Austin, Texas, storyboarded how they intend to use blockchain technology to store vital records for homeless people; and a team from New Rochelle, N.Y., whipped up a crude but clickable smartphone app that simulated their plan to help residents visualize city developments before they’re built.

[Read our explainer: What is prototyping?]

“At first, we were struggling a little bit, looking at the LEGOs and the art stuff and the cardboard,” said South Bend, Ind., Chief Innovation Officer Santi Garces. His city intends to develop a subsidized ride-sharing program to help low-income residents get to work. To simulate the workers’ experience, Garces and his colleagues built a cardboard car and a cutout smartphone. “Even if the prototype was very low fidelity — no one is able to ride the cardboard box to work — it prompted people to interact with it and give feedback,” Garces said.

As members of other teams came around to play with the cardboard props, they asked questions about how the program would be marketed. And those questions, in turn, raised others that the team will have to answer with regard to employers. “One of the virtues of prototyping is it takes risk away from doing things,” Garces explained. “You’re able to demonstrate and validate, without investing a lot of money, and while maintaining the ability to change or pivot.”

The Louisville, Ky., team also got valuable feedback quickly. Their idea is to deploy drones to shooting scenes in hopes of capturing video footage before police officers are able to arrive. Through a role-playing exercise — team members pretended to be either the drone, the drone base, a first responder, or an analyst at the city’s real-time crime center — important questions came up. How will residents know the drone belongs to the police? Could they mistake the drone as the source of the gunfire? And will they worry the drones are invading their privacy?

Grace Simrall, Louisville’s chief of civic innovation and technology, said the exercise helped the team understand how integral community engagement will be to the success of their idea. “We realized how important the framing is,” she said. “We’ll need to work with residents in neighborhoods to build their trust.”

[Read: Unleashing the power of public prototyping]

Prototyping helped the team from Danbury, Conn., spot and troubleshoot a flaw they hadn’t previously noticed in their idea — to increase the local supply of affordable and high-quality home-based daycare services. The hitch? How to help unlicensed providers get licensed without displacing the kids in the process. The team brainstormed a solution and was grateful the exercise helped flag the issue early.

Megan Chrysler, coordinator for Danbury’s Promise for Children Partnership, said at first they were laughing that the storyboarding technique they were using had them drawing sequences of pictures, almost like a comic strip. “And then we realized the value of drawing those pictures,” she said. “We’re doing the storyboard and came to that square and we looked at each other. What do we do with these kids?”

A common practice in the private sector, prototyping new programs and services is less routine in the public sector. Chrysler came away from Ideas Camp convinced that should change. “As somebody who manages a lot of grants, if our grantors had us go through this process, we could provide much better data and feedback to them,” she said. “It may feel like a big task on the front end, but I think the results at the end are valuable to everybody.”

Raimundo Rodulfo, information technology director for Coral Gables, agreed. He said his team had been eager to implement their idea — to buy solar panels and begin constructing their microgrid. But the prototyping process forced them to slow down just enough to learn lessons that will likely save them time and money later.

“It’s a systematic process — you make progress with every step and you improve your idea more and more,” he said. “I think we should apply that creative thinking and design thinking to many other things we do.”

The 35 city teams now head home to test their ideas using increasingly sophisticated and more life-like prototypes. They’ll also enlist the help of citizens as they reshape their final proposals to the Mayors Challenge selection committee.

“These cities will be asking residents to co-create in ways they never have before,” said Bloomberg Philanthropies’ Stephanie Wade, who helped design the prototyping curriculum for the Mayors Challenge. “In doing so, they will be communicating: ‘This is not a finished product, we don’t have the answers yet, but we have the start of an idea and we really do want you to help us make it better’.

“It’s great to see cities trying something they never have before,” Wade continued. “Because they are so used to problem solving in one direction, which is, ‘We’re going to develop a solution among ourselves in city hall and then bring it out to the public and hope that it actually solves the problem.’ Now a seed has been planted with these teams to help them solve public problems in new ways. And whether they win the Mayors Challenge competition or not, these 35 teams are different now, and we hope they bring these skills back to their cities and get other people in their government to start trying this approach, too.”