How Houston is helping young men of color reach their full potential

Eighteen-year-old Asa Singleton says he’s always dreamed of working for the city of Houston. He even interned for a city council member when he was 14. But two years later, when Singleton got in a fight that resulted in criminal charges, he feared his hopes for a city hall career — or any job at all — might be dashed.

Then Singleton heard about ReDirect, a city program that offers at-risk boys and young men of color mentorship instead of punishment and, upon completion, the possibility of erasing their juvenile criminal record. He signed up, quickly bonded with a mentor, and, seven months later, completed ReDirect’s requirements. Singleton’s record has now been expunged, and he is working part-time for the city while finishing up with school. “Honestly, if it wasn’t for [ReDirect], I would be in jail right now,” he said. “If it wasn’t for them, there would be no me.”

As in too many cities across the country, statistics in Houston show a troubling trend. According to the city’s 2015 local action plan, black men in Houston are seven times more likely than their white peers to have an encounter with law enforcement. Additionally, young black and Hispanic men in the city are more than twice as likely as white men to live in poverty. ReDirect and other programs like it — aimed at improving school readiness, literacy, nutrition, and college preparation — have so far worked with more than 25,000 students in an effort to open opportunities and reduce disparities.

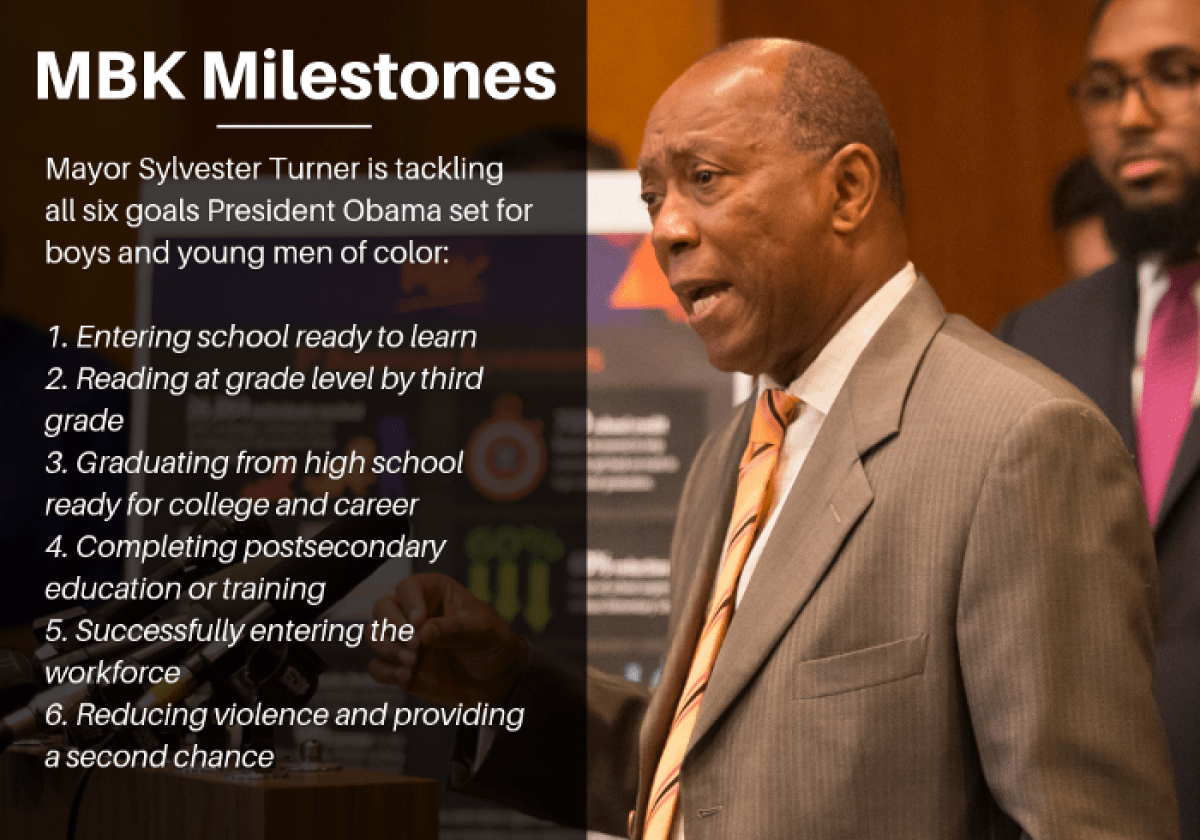

These initiatives are part of a nationwide movement sparked in 2014 when President Obama launched the My Brother’s Keeper Community Challenge, which asked city and community leaders to work together to find new ways to improve life for boys and young men of color. While 250 cities accepted the challenge, Houston responded with exceptional ambition and purpose, devoting a team of ten full-time staff to this work. It’s still in the early days for an initiative focused on long-term change, but rising reading scores and declines in school suspensions are signs that Houston is moving in the right direction.

“Success in addressing the persistent gaps in outcomes for young men of color in the country requires strong and unwavering leadership, trust, community-wide collaboration, and a strong management approach,” said Niiobli Armah of Bloomberg Associates, who works closely with Houston and two dozen other cities on their My Brother’s Keeper implementation strategies. “Houston is one of the most diverse cities in the country. If they get it right, we stand to learn a great deal about what local government can actually do to reduce racial disparities.”

Houston’s success is, in part, the story of bold leadership by two mayors who maintained momentum across two administrations: Annise Parker launched the effort in 2015. Sylvester Turner, who took office a year later, has pledged to build upon these efforts. My Brother’s Keeper, Turner says, is like “filling the potholes in the lives of our youth.”

The city’s commitment to collaboration has been another key to its success. “We brought together the agency heads that were mission-minded in the health, education, employment, and justice sectors, and we formalized a group,” said Noël Pinnock, who coordinates My Brother’s Keeper for Houston. “Now, that entire group of agency principals serves as a steering committee that helps guide the work through.”

What this group realized was that Houston already had a vast network of government, nonprofit, and community organizations doing great work in this area. But they were missing a common sense of purpose and a structure to help them meet their shared goals. Pinnock’s team rallied more than 250 groups to adopt the six milestones outlined by the My Brother’s Keeper Challenge and, using that framework, directed their collective efforts toward three target neighborhoods.

One such collaboration is Momentum Academy, which provides high schoolers who fall behind in their coursework a chance to catch up. It’s a partnership between the Houston schools, which supplies the teachers, and the Health Department, which supplies workspace in its neighborhood health clinics. The idea is to give students a place outside of school where they can learn in smaller groups and get more individualized attention. Already, it’s helped more than 145 students recover more than 700 credit hours.

Another collaboration uses counselors, mentors, and social workers to both identify at-risk youth at the elementary-school level and use methods other than suspension to address disruptive classroom behavior. One school in the program has seen suspensions fall (by 60 percent) and 3rd-grade reading levels jump (by 5 percent).

“We’re not trying to boil the ocean,” Pinnock said. “We’re taking it one cup at a time.”

Change in Houston may be coming bit by bit, but Asa Singleton can feel the difference. Thanks to his work with ReDirect, Singleton is well on his way to the job of his dreams, recently accepting Mayor Turner’s invitation to sit on his Youth Council and speak out against youth violence. “If it wasn’t for MBK, I wouldn’t have had the opportunity to work in the Mayor’s office,” Asa said. “It’s helped me open doors that I didn’t know I could open.”