Cities try ‘learning hubs’ to keep kids on track with online school

As a school year unlike any other begins with most children learning online, some parents are forming “pandemic pods” with other families to split the cost of hiring a tutor to keep their children up to speed on schoolwork and showing up to Zooms on time.

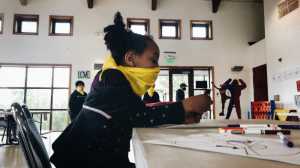

Now, a growing number of cities are setting up similar programs for families who can’t afford such an arrangement. They’re called “learning hubs,” and they’re the latest local-government innovation bubbling up in response to the COVID-19 crisis.

San Francisco is rolling out one of the largest such programs, set to serve 6,000 children this fall. Starting September 14, students in San Francisco can go to recreation centers, branch libraries, and other sites across the city to take their virtual classes in small socially-distanced groups supervised by staff from nonprofits the city has partnered with. The free program is targeted at students living in public housing, homeless youth, those in foster care, English-language learners, and low-income families of color.

“In a pandemic, you really do see the inequities in a much sharper way,” said Maria Su, head of the city’s Department of Children, Youth and Their Families. During the emergency shift to online learning this spring, Su said, less than a third of the city’s most disadvantaged students would log in for remote learning for at least 30 minutes a week. “That’s unacceptable. We have failed a very large group of children, and we cannot continue to pretend that we don’t see it.”

San Francisco’s learning hubs are meant to give students structure at a disruptive moment in their lives, while taking care of several pandemic needs at once. In addition to tutoring and support with classwork, the hubs will offer full-day childcare so parents can go to work; internet access for students who don’t have it at home; meals for children who normally get those at school; and opportunities for children to play and socialize safely, which is so critical for their emotional health.

“We knew families who had the means were out hiring teachers and tutors for their children,” Su said. “We wanted to make sure our high-need families knew that ‘we got your back’.”

[Get the City Hall COVID-19 Update. Subscribe here.]

Similar programs are springing up in cities across the country, at no or little cost to families. In New Orleans, learning hubs at rec centers and libraries are intended for children who don’t have internet access at home or who lack adult supervision during school hours. In Memphis, local churches and the YMCA are key partners in the model. And in Orlando, learning hubs offer flexible schedules so that parents can sign up just for one or two days a week, if that’s all they need.

Orlando is offering the learning hubs despite the fact that the local schools are open for in-person instruction. They’ve set them up at six recreation centers across the city. Each center is equipped to handle two pods of nine students, with each group supervised by a counselor employed by the city’s Parks and Recreation Department. Students must wear masks, stay six feet apart from each other, and have their temperature checked at drop-off. The cost — $5 per day — is waived for families with low incomes, who make up most of the users so far.

“We had seen where people were doing these pods privately, so we decided we ought to make that available to our parents here in the city of Orlando at a low-cost rate,” Mayor Buddy Dyer said in an interview. Dyer notes that about 70 percent of Orlando public school students have chosen distance-learning options over in-person school. “This is a proven, safe way to go about it,” he said. “We don’t have kids changing classes in hallways.”

In San Francisco, the learning hubs program builds on earlier versions of childcare options the city has set up during the pandemic. In March, the city began offering emergency child care for healthcare workers, serving about 500 children. Over the summer, the city offered modified summer camps, taking precautions to keep children and staff safe. According to Su, only 38 of the 3,000 children served in that program tested positive for COVID-19, and none of those cases were traced back to camp as the source of the infection.

Now, the learning hubs model will double the number of children served. This kind of iterative approach is one of the lessons Su said cities can take from San Francisco’s experience. “It’s with a lot of practice and many months of conversations that we are where we are,” she said. “There’s tons of logistics involved. Cities should start small because they need to get all the kinks worked out.”

Su points to two other things that have helped San Francisco move with ambition. First, the city has a dedicated funding stream for children, youth, and families, which she said gives her department flexibility to move farther and faster than cities that have to cobble together the funds. Second, her department has built strong working relationships with other city departments, such as Recreation and Parks, Libraries, and Technology, as well as nonprofit agencies in the community that run youth programming.

“Because we have a very strong working relationship with our providers and our city departments, we were able to quickly pivot,” Su said. “Without money and without the trust of good working relationships, it’s hard to be innovative.”