5 keys for enabling digital transformation to flourish

(Shutterstock/alphaspirit.it)

When COVID-19 lockdowns first rippled across the world, city leaders moved swiftly to digitize services that previously required residents to fill out paper forms or visit City Hall in person.

Now, as local leaders seek to consolidate those gains and take digital transformation to the next level, they’re finding that the key to this work isn’t technology. It’s people—city staff, in particular—and their comfort with new ways of working and relating to residents.

That’s a clear lesson from the Bloomberg Philanthropies Digital Innovation Initiative, which ran from 2019 through early this year. In the program, eight European capital cities chose a single service to either digitize for the first time or to upgrade a previous effort. Delivery teams in all eight cities received expert coaching from the London-based consultancy Futuregov (now TPXImpact) in something that was new to many of them: how to use human-centered design to transform those services around residents’ needs.

The cities saw some big wins as a result. Bratislava, Slovakia, for example, launched a new way for residents to pay property taxes online, overhauling an earlier system that almost nobody used. In Vilnius, Lithuania, city leaders launched a new web portal to help residents better understand their options when it comes to social care. Sofia, Bulgaria, cut through many layers of red tape to enable residents to register a change of address without having to visit City Hall, as they previously had to.

One through line in all of these stories of digital transformation: the need for culture change at City Hall. Here are five lessons the European cities learned about how to do it that local leaders everywhere can learn from.

Change starts at the top

When it comes to digital transformation, mayors don’t need to master the technical details, of course. But they do have an important leadership role to play.

It’s critical for the mayor not only to say that digital is a priority but also to back that up with resources. Mayors also play a key role in empowering staff to change the status quo and provide them cover when tough decisions must be made.

That’s exactly what Bratislava Mayor Matúš Vallo did when he entered office in 2018. Vallo came in with a clear vision for digital services that are engaging, easy to use, and meet the needs of residents. To manage the effort, he created the city’s first-ever Chief Information Officer role and appointed Petra Dzurovcinova, who had deep private-sector experience, to the position.

Through the Digital Innovation Initiative, Bratislava set out to fix the way residents pay property taxes online. Back in 2016, the city had spent €4 million on a website to enable online payments, but residents found it so confusing to use that they continued to come in to the front office to pay in person for 90 percent of the transactions. Dzurovcinova and her team worked closely with residents to design, prototype, and test a number of alternatives to design a process that users find more intuitive. The solution they co-designed and built is proving much more popular with residents and promises to save the city €480,000 on paper and postage.

Along the way, Vallo hosted regular meetings with the innovation team. That not only reinforced the understanding that fixing property-tax payments was a key mayoral priority, but also affirmed the team’s culture of openly sharing unfinished work in progress and its ethos of acting on residents’ insights. Vallo also influenced a radical shift in policy, shifting the Tax Department from paper billing to a fully digital service. As Dzurovcinova says, Mayor Vallo was “a huge driver and one of the biggest advocates for the change.”

Understand residents’ real needs

A mistake cities often make with digital services is to start with the technology. The better place to start is with the people who will actually use the service.

All of the cities in the Digital Innovation Initiative began their service redesign journey by interviewing residents, business owners, and other stakeholders, with a goal of deeply understanding their needs before doing any technical design or coding. What city leaders heard often surprised them.

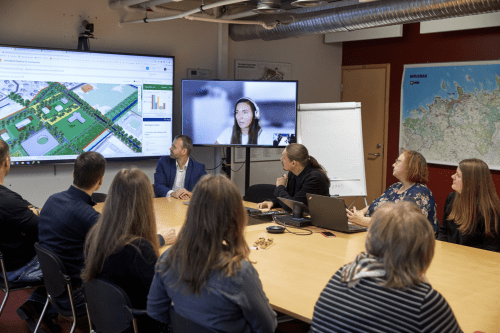

In Tallinn, Estonia, for example, they set out to address an urban planning challenge that vexes cities everywhere: New development triggers lots of resident complaints but little useful feedback. A team from Tallinn’s Urban Planning and IT departments started out with the idea that providing 3D renderings of proposed changes would help residents visualize changes better. What they learned from interviewing about 20 residents added important new dimensions to their thinking.

One thing that became clear was that residents weren’t just confused about what new development would look like; they also didn’t know when was the right time in the development cycle to offer feedback or how to do it. That insight led the Tallinn team to think more broadly about incorporating the new 3D maps into a more transparent end-to-end digital process to help residents more easily discover plans, offer their ideas, and understand what effect their feedback has on the final project.

City leaders in Helsinki had a similar experience. When they set out to redesign services that help unemployed workers find jobs, they learned a lot from talking with users of that service. The biggest role technology could play, they found, wasn’t very high-tech at all: Sending job seekers a text message to remind them to show up for their appointment with an employment agent. Otherwise, what mattered most was that job seekers and employment agents have deeper interactions in their face-to-face conversations.

“For us, it highlights the importance of human-centric service design,” says Mikko Rusama, Helsinki’s Chief Digital Officer. “We might have bought an expensive app without understanding the problem

we were trying to solve or what people actually want. These learnings have already saved a lot of money for the city.”

Create space for experimentation, learning, and failure

One reason digital projects sometimes flop in the public sector, ironically, is the quest for perfection. The urge to make sure every piece of a complex program works perfectly before going live has a way of breaking deadlines and busting budgets.

In the Digital Innovation Initiative, city leaders flipped the script. Instead of starting with a big project and striving to make it perfect, they started with small experiments, tested prototypes with users, and iteratively built new services based on what they learned along the way. It’s an ethos that requires getting comfortable with small failures, and prioritizing learning and adaptation above all else.

In Dublin, Ireland, for example, city leaders set out to digitize a clunky paper-based system for handling maintenance requests in publicly run housing. They prototyped ways of tackling different parts of the service journey, from informing tenants about which jobs are eligible for repairs to capturing details of the maintenance request to sharing updates about repairs in progress. Working with low-fidelity prototypes—using easy and available technology like the messaging platform WhatsApp—allowed the team to quickly test emerging solutions, adapt to feedback, and refine what they are turning into a beta version of an app that can continue to be refined.

Shane Waring of the Dublin City Council’s Transformation Unit says this is a fundamental shift from the city’s usual approach. “Normally, this organization would assume that if you did a big job to transform a service, the digital thing has to be the absolute final product that’s going to exist for the next 20 years,” Waring says. “This project has been an opportunity to just do a test that only needs to exist for four weeks. It’s a little bit risky, but it’s a safe risk. Normally, that kind of mindset just doesn’t exist.”

Bring diverse perspectives in to your teams

In Vilnius, city leaders set out through the Digital Innovation Initiative to improve elderly residents’ access to social care services. The city’s website for these services was a mess. People who were looking for home care or food support, either for themselves or for an aging parent, had a hard time figuring out what options were available to them.

To tackle the problem, Chief Innovation Officer Egle Radvile pulled together a multidisciplinary team of people from across City Hall. They included social workers, administrative specialists and a department head, all with deep expertise in social-care services, as well as Radvile, an IT manager, and project manager to offer more technical knowledge. The diversity of perspectives enabled fresh thinking to emerge and was a big factor in the project’s ultimate success.

As they talked with residents about their difficulties accessing care services, team members without expertise in social care were able to ask lots of questions and challenge the status quo. At the same time, those with subject-matter expertise knew everything about how services worked. Together, they worked with residents to rebuild the city’s social care website in a way that makes it much easier for users to find information they’re looking for. As a result, applications for care jumped by more than 50 percent.

"In the team, we came from different spheres,” says Project Manager Aleksandra Cerniauskiene. “That was our strength.”

Questioning the status quo doesn’t have to mean blowing it up

A big obstacle to digital transformation is the feeling among city hall veterans that longstanding practices are not allowed to change. It’s always been done this way. To make progress, city leaders in the Digital Innovation Initiative found they had to constantly interrogate the status quo. “There was a way of working and people were just used to doing it this way,” says Bratislava’s Dzurovcinova. “So we started with asking them: Why? Let’s just explore which law is actually telling us to do it this way. It doesn’t need to be this complicated.”

At the same time, there are legitimate constraints to navigate. That’s what city leaders in Sofia found as they set out to digitize the process whereby residents register a change of address with the municipality — a procedure that residents are legally required to do when they move, and had previously required them to make a trip to City Hall.

First, they discovered that the city’s legacy IT systems relied on outdated technology that would make back-end data sharing difficult. That meant the Sofia team had to make do with some manual workarounds until a long-term solution can be found. They also found that under Bulgarian law, in order to verify a resident’s identity online, it would require the resident to scan an ID and show their face live on camera so that a worker at City Hall can check it. It’s not seamless. But the growing number of residents choosing this method over making the trip to City Hall is a sign that it’s an improvement.

“Our team had to adapt to the fact that some of the requirements cannot be changed at this time,” says Elitsa Panayatova with Sofia Green, an NGO that partnered with the city on the project. “So we had to design the service in a way that incorporates the restrictions and still offers a front-end digital service, while leaving the rest for future improvements.”