COVID-19 Federal Assistance e311

Program

COVID-19 Federal Assistance e311Topics

Compliance & ReportingFunding Source

American Rescue Plan ActDoes the ARP allow for funding of site preparation to lower the cost of development of vacant or abandoned property?

Yes, the ARP allows funding of site preparation for the development of vacant or abandoned property in many circumstances.

On January 6, 2022, the U.S. Department of the Treasury (“Treasury”) released the Final Rule implementing the Coronavirus State Fiscal Recovery Fund and the Coronavirus Local Fiscal Recovery Fund (collectively, the “CSLFRF”).[1] This guidance states that certain services for vacant or abandoned properties are eligible for CSLFRF funding when used to address the public health and negative economic impacts of the pandemic on disproportionately impacted households or communities.[2] The guidance defines vacant or abandoned properties as “generally those that have been unoccupied for an extended period of time or have no active owner.”[3] Specifically, demolition and greening (or other structure or lot remediation) of vacant or abandoned properties, including residential, commercial, or industrial buildings, is an eligible use of funds.[4]

In one section, entitled “Building strong, healthy communities through investments in neighborhoods,”[5] Treasury enumerates several eligible activities relating to services for vacant or abandoned properties. They include the following:

- Rehabilitation, renovation, maintenance, or costs to secure vacant or abandoned properties to reduce their negative impact;

- Costs associated with acquiring and securing legal title of vacant or abandoned properties and other costs to position the property for current or future productive use;

- Removal and remediation of environmental contaminants or hazards from vacant or abandoned properties, when conducted in compliance with applicable environmental laws or regulations;

- Demolition or deconstruction of vacant or abandoned buildings (including residential, commercial, or industrial buildings) paired with greening or other lot improvement as part of a strategy for neighborhood revitalization;

- Greening or cleanup of vacant lots, as well as other efforts to make vacant lots safer for the surrounding community;

- Conversion of vacant or abandoned properties to affordable housing; and

- Inspection fees and other administrative costs incurred to ensure compliance with applicable environmental laws and regulations for demolition, greening, or other remediation activities.

Recipients should also be aware of federal, state, and local laws that apply to these eligible activities, and potential effects on low-income housing. The Final Rule states the following:

Treasury presumes that demolition of vacant or abandoned residential properties that results in a net reduction in occupiable housing units for low- and moderate-income individuals in an area where the availability of such housing is lower than the need for such housing would exacerbate the impacts of the pandemic on disproportionately impacted communities and that use of [C]SLFRF funds for such activities would therefore be ineligible. This includes activities that convert occupiable housing units for low- and moderate-income individuals into housing units unaffordable to current residents in the community. Recipients may assess whether units are “occupiable” and what the housing need is for a given area taking into account vacancy rates… local housing market conditions (including conditions for different types of housing like multi-family or single-family), and applicable law and housing codes as to what units are occupiable. Recipients should also take all reasonable steps to minimize the displacement of persons due to activities under this eligible use category, especially the displacement of low-income households or longtime residents.[6]

Last Updated: February 3, 2022

Program

COVID-19 Federal Assistance e311Topics

Compliance & Reporting, Workforce & Economic DevelopmentFunding Source

American Rescue Plan ActDoes Treasury Guidance indicate whether municipalities must provide tax documentation to ARP CSLFRF subrecipients (such as persons or businesses receiving rental assistance)?

At the time of this writing, the U.S. Department of the Treasury (“Treasury”) has not issued any guidance mandating local governments to provide tax documentation to subrecipients of funding from the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (“ARP”). The United States Internal Revenue Service’s (“IRS”) guidance published on November 17, 2021, address many issues relating to taxes. However, municipalities should discuss their specific facts and circumstances with tax and financial professionals prior to reaching any final conclusions.

According to IRS Frequently Asked Questions (“FAQs”), some uses of Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (“CSLFRF”) may trigger tax consequences. If feasible, the state or local government providing funding should consider expressly informing subrecipients whether they should include CSLFRF funding as gross taxable income. As noted above, there is currently no express requirement to provide subrecipients with this information or tax documentation.

Generally, individuals must include any payment or accession to wealth from any source as gross income, unless an exclusion applies.[1] However, subrecipients may avail themselves of at least one possible exclusion to this rule. Under Section 139 of the Internal Revenue Code (the “Code”), certain payments made by a state or local government to individuals in connection with the COVID-19 pandemic may qualify as disaster relief payments, which are excluded from the subrecipient’s gross income. A payment by a state or local government generally will be treated as a qualified disaster relief payment under Section 139 if the payment is made to or “for the benefit of” an individual to:

- Reimburse or pay reasonable and necessary personal, family, living, or funeral expenses incurred as the result of a qualified disaster, or

- Promote the general welfare in connection with a qualified disaster.[2]

- Because the COVID-19 pandemic was federally declared a disaster, ARP CSLFRF payments to sub recipients could potentially qualify as disaster relief payments for the purposes of Section 139 of the Code. Qualified disaster relief payments generally do not require additional documentation such as a 1099-MISC, as these payments are not income.

Municipalities should note that payments are not treated as qualified disaster relief payments if the payments constitute compensation for services performed by an individual. Additionally, payments made to or for the benefit of an individual are not treated as qualified disaster relief payments to the extent that the expense of the individual compensated by such payment is otherwise compensated by insurance or otherwise.[3]

The FAQ further elaborates on specific instances where payments to recipients may be included as taxable income. For example, subrecipients receiving premium pay or bonuses from CSLFRF are required to report those funds as gross income.[4] In contrast, rental payments or utility assistance could in some cases be excluded from gross income because these payments are made by a state or local government to individuals and are intended to pay for personal expenses incurred during the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, such rental and utility assistance payments are generally classified as qualified disaster relief payments under Section 139 of the Code.[5] However, as noted above, municipalities should consult an appropriate tax professional to address their own specific circumstances. For example, the manner in which rental assistance payments are made could affect whether the payments qualify as gross income (and thus, whether a 1099 or similar documentation is required).[6]

For more information, municipalities may refer to the IRS FAQ and continue to monitor Treasury’s website on CSLFRF for forthcoming information and guidance.

Last Updated: February 3, 2022

[1] U.S. Internal Revenue Service, Frequently Asked Questions for States and Local Governments on Taxability and Reporting of Payments from SLFRF, available at: https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/frequently-asked-questions-for-states-and-local-governments-on-taxability-and-reporting-of-payments-from-coronavirus-state-and-local-fiscal-recovery-funds.

[2] Id.

[3]Id.

[4]Id.,at FAQ #1.

[5] Id., at FAQ #9.

Program

COVID-19 Federal Assistance e311Topics

Fund Planning & AllocationFunding Source

American Rescue Plan ActWhat steps can municipalities that operate on a fiscal year take to accommodate current annual reporting benchmarks (based on the calendar year), and what is the possibility that regulations may change to allow for different year starts and ends?

Reports on the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s (“Treasury”) Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (“CSLFRF”) are due either annually or on calendar quarters. In particular, the Project and Expenditure Reports require key financial grant reporting information and are due either annually or quarterly based on calendar quarter ends, depending on recipient type.[1] Entities that submit annual Project and Expenditure reports are required to submit by April 30 of each year until 2027. Entities that submit quarterly Project and Expenditure reports are required to submit to Treasury within 30 calendar days after the end of each calendar quarter.

The following table summarizes all quarterly reporting timelines:[2]

|

Report |

Year |

Quarter |

Period Covered |

Due Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

2021 |

2-4 |

March 3 – December 31 |

January 31, 2022 |

|

2 |

2022 |

1 |

January 1 – March 31 |

April 30, 2022 |

|

3 |

2022 |

2 |

April 1 – June 30 |

July 31, 2022 |

|

4 |

2022 |

3 |

July 1 – September 30 |

October 31, 2022 |

|

5 |

2022 |

4 |

October 1 – December 31 |

January 31, 2023 |

|

6 |

2023 |

1 |

January 1 – March 31 |

April 30, 2023 |

|

7 |

2023 |

2 |

April 1 – June 30 |

July 31, 2023 |

|

8 |

2023 |

3 |

July 1 – September 30 |

October 31, 2023 |

|

9 |

2023 |

4 |

October 1 – December 31 |

January 31, 2024 |

|

10 |

2024 |

1 |

January 1 – March 31 |

April 30, 2024 |

|

11 |

2024 |

2 |

April 1 – June 30 |

July 31, 2024 |

|

12 |

2024 |

3 |

July 1 – September 30 |

October 31, 2024 |

|

13 |

2024 |

4 |

October 1 – December 31 |

January 31, 2025 |

|

14 |

2025 |

1 |

January 1 – March 31 |

April 30, 2025 |

|

15 |

2025 |

2 |

April 1 – June 30 |

July 31, 2025 |

|

16 |

2025 |

3 |

July 1 – September 30 |

October 31, 2025 |

|

17 |

2025 |

4 |

October 1 – December 31 |

January 31, 2026 |

|

18 |

2026 |

1 |

January 1 – March 31 |

April 30, 2026 |

|

19 |

2026 |

2 |

April 1 – June 30 |

July 31, 2026 |

|

20 |

2026 |

3 |

July 1 – September 30 |

October 31, 2026 |

|

21 |

2026 |

4 |

October 1 – December 31 |

March 31, 2027 |

Notably, Treasury’s Final Rule on CSLFRF allows recipients to calculate revenue loss based on a fiscal year or a calendar year as long as the recipient takes a consistent approach through the period of performance.[3]

A CSLFRF recipient should consider tracking its expenditures and obligations monthly to accommodate reporting benchmarks that differ from the recipient’s operating fiscal year. Monthly captures of financial and programmatic data allow recipients to generate reports for both their fiscal year and annual reports for Treasury more easily. Further, monthly tracking could provide the added benefit of providing more timely and useful financial information to management, who could use the information to produce financial statements that follow a calendar year or any other fiscal year-end and may prove helpful in completing CSLFRF reports for Treasury.

Last Revised: March 31, 2022

[1] Department of Treasury, “Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds—Compliance and Reporting Guidance,” Version, 3.0, February 28, 2022, at 14-19 available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Compliance-and-Reporting-Guidance.pdf.

[2] Id., at 18.

[3] Treas. Reg. 31 CFR 35 at 249, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Final-Rule.pdf.

Program

COVID-19 Federal Assistance e311Topics

Compliance & Reporting, Fund Planning & AllocationFunding Source

American Rescue Plan ActIf a city decides to use Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (“CSLFRF”) for payments to individual residents impacted by the pandemic, is there any documentation that confirms that the funds are non-countable against existing benefits?

The U.S. Department of the Treasury (“Treasury”) guidance does not clearly indicate whether cash assistance provided to households to address the negative economic impacts of the COVID-19 public health emergency would impact recipients’ income eligibility for other federal benefit programs. Municipalities should consult public guidance issued by other federal agencies regarding specific benefit programs. For example, the U.S. Social Security Administration website states: “COVID-19 emergency financial assistance paid from a federal, state, or local government source will not affect your Social Security benefits.”[1]

Treasury’s Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (“CSLFRF”) Final Rule allows for the use of funds to address the negative economic impacts of the COVID-19 public health emergency.[2] Such assistance includes direct cash assistance to households or populations.[3] Municipalities can consider cash transfers for those households or populations who experienced disproportionate harms due to the pandemic,[4] noting that such transfers must be reasonably proportional to the negative economic impact they are intended to address.[5] Treasury’s initial approach:

[I]ncluded as an enumerated eligible use cash assistance and provided that cash transfers must be “reasonably proportional” to the negative economic impact they address and may not be “grossly in excess of the amount needed to address” the impact. In assessing whether a transfer is reasonably proportional, recipients may “consider and take guidance from the per person amounts previously provided by the Federal Government in response to the COVID-19 crisis,” and transfers “grossly in excess of such amounts” are not eligible.[6]

Treasury maintains this enumerated eligible use in its CSLFRF Final Rule and states:

Treasury has reiterated in the final rule that responses to negative economic impacts should be reasonably proportional to the impact that they are intended to address. Uses that bear no relation or are grossly disproportionate to the type or extent of harm experienced would not be eligible uses. Reasonably proportional refers to the scale of the response compared to the scale of the harm. It also refers to the targeting of the response to beneficiaries compared to the amount of harm they experienced; for example, it may not be reasonably proportional for a cash assistance program to provide assistance in a very small amount to a group that experienced severe harm and in a much larger amount to a group that experienced relatively little harm.[7]

Although Treasury refers to existing federal government programs in relation to direct cash assistance under CSLFRF, it appears to do so only to provide guidance on the appropriate size of permissible cash transfers.

Treasury may provide additional information when it issues new Frequently Asked Questions (“FAQs”) associated with the Final Rule.[8]

Last Revised: April 1, 2022

[1] U.S. Social Security Administration, Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19), Monthly Benefits and Other Financial Help, “Will my Social Security retirement, survivors, or disability insurance benefits be reduced or stopped if I get COVID-19 emergency financial assistance?”, available at: https://www.ssa.gov/coronavirus/categories/monthly-benefits-and-other-financial-help/.

[2] Treas. Reg. 31 CFR 35 at 4, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Final-Rule.pdf.

[3] Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, Frequently Asked Questions (as of January 2022) – FAQ #2.5, at 5, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRPFAQ.pdf.

[4] For more information on which households and populations qualify as having experienced disproportionate harms due to the pandemic, see the Bloomberg e311 Q&A available at: https://bloombergcities.jhu.edu/faqs/how-will-use-funds-category-authorizing-spending-arp-funds-respond-public-health-emergency.

[5] Treas. Reg. 31 CFR 35 at 26, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Final-Rule.pdf.

[6] Id., at 90.

[7] Id., at 90-91.

[8] Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, Frequently Asked Questions (as of January 2022), at 1, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRPFAQ.pdf.

Program

COVID-19 Federal Assistance e311Topics

Fund Planning & AllocationFunding Source

American Rescue Plan ActIs hazard pay an allowable expense under Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund (“ESSER”) II or III?

Neither the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (“ESSER”), ESSER II (as found in the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act), nor ESSER III (as set forth in the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (“ARP”)) funds expressly authorize hazard pay. However, there may be alternative funding sources available to provide employees with hazard or premium pay, especially where an employee qualifies as an “eligible worker” under the ARP.

Title II, Part I, Section 2001 of the ARP, which covers ESSER III, states that funds may be used to “maintain the operation of and continuity of services in local educational agencies and continuing to employ existing staff of the local educational agency.”[1] Section 2001 does not identify hazard pay or premium pay as eligible uses of ESSER III funds.

Regarding ESSER II funds, the U.S. Department of Education Fact Sheet states “ESSER II funds may be used for the same allowable purposes as ESSER and ARP ESSER, including hiring new staff and avoiding layoffs.” [2] The Coronavirus Aid Relief, and Economic Security (“CARES”) Act Section 18003 ESSER, [3] like the ESSER section of the ARP, does not identify hazard or premium pay as an eligible use of funds, but allows for:

[o]ther activities that are necessary to maintain the operation of and continuity of services in local educational agencies and continuing to employ existing staff of the local educational agency. [4]

Though ESSER II or III do not appear to allow hazard or premium pay, there are other mechanisms for municipalities to access similar funds in certain situations. ARP Section 9901 of the U.S. Department of the Treasury (“Treasury”) Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (“CSLFRF”) allows for funds to be used to:

respond to workers performing essential work during the COVID–19 public health emergency by providing premium pay to eligible workers of the State, territory, or Tribal government that are performing such essential work, or by providing grants to eligible employers that have eligible workers who perform essential work. [5]

The ARP’s section on the CSLFRF identifies eligible workers as:

those workers needed to maintain continuity of operations of essential critical infrastructure sectors and additional sectors as each Governor of a State or territory, or each Tribal government, may designate as critical to protect the health and wellbeing of the residents of their State, territory, or Tribal government. [6]

Therefore, if the Governor or requisite governmental authority of a particular state has deemed teachers as essential workers, they may be able to receive premium pay under the CSLFRF. Section 9901 defines premium pay as:

an amount of up to $13 per hour that is paid to an eligible worker, in addition to wages or remuneration the eligible worker otherwise receives, for all work performed by the eligible worker during the COVID–19 public health emergency. Such amount may not exceed $25,000 with respect to any single eligible worker.

Last Revised: November 3, 2021

[1] American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 § 9901, Pub. L. No. 117-2, amending 42 U.S.C. § 801 et seq., at Section 2001(e)(1)(R), available at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/1319/text#HAECAA3A95C4E4FFAB6AA46CE5F9CB2B5.

[2] Department of Education, U.S. Department of Education Fact Sheet - American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund (ARP ESSER), available at: https://oese.ed.gov/files/2021/03/FINAL_ARP-ESSER-FACT-SHEET.pdf.

[3] Coronavirus Aid, Relief, Economic Security Act (CARES Act), Pub. L. No. 116–136, 134 Stat. 281 (2020), at Section 18003, available at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/748/text./.

[4] Id., at Section 18003(d)(12).

[5] American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 § 9901, Pub. L. No. 117-2, amending 42 U.S.C. §801 et seq., at Section 602(c)(1)(B), available at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/1319/text#HC028912924A04512A1F80BFA0F1C1051.

[6] Id., at Section 602(g)(2).

Program

COVID-19 Federal Assistance e311Topics

Compliance & ReportingFunding Source

American Rescue Plan ActIf a city has made a determination and documented that a project fits within a specific eligibility category under ARP, can the eligibility determination later be changed if our compliance team determines the initial classification is no longer correct?

Municipalities will have an opportunity to reopen and provide edits to their submitted reports any time before the reporting deadline, with the exception of the Interim Report, which cannot be reopened and edited after submission. The U.S. Department of the Treasury’s (“Treasury”) Portal for Recipient Reporting State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds User Guide (the “User Guide”) and the Project and Expenditure Report User Guide provide the following guidance on editing or updating previously submitted reports:

- Interim Report: No changes will be allowed after the initial submission. Any updates will be captured when the first Project and Expenditure Report is submitted.[1]

- Project and Expenditure Reports: Recipients will have an opportunity to reopen and provide edits to their submitted Project and Expenditure Reports any time before the reporting deadline. Recipients will then be required to re-certify and submit the report again to properly reflect any edits made.[2] Specific instructions for corrections and submissions can be found on page 7 of the Project and Expenditure Report User Guide.[3]

- Recovery Plan: Recipients will be allowed to reopen and update their submitted Recovery Plan report any time before the reporting deadline. Recipients should provide concurrent updates to the publicly posted version of any edited report.[4], [5]

The User Guide instructs recipients to follow the steps outlined above if a municipality deems a previously reported eligible expense to be ineligible. The User Guide states that “[r]ecipients can make corrections to reporting to adjust for ineligible uses, and must pay for that expense using non-SLFRF funding.”[6]

As a good practice, when amending information on a quarterly or annual report, municipalities should add a footnote, when the reporting template allows, indicating that the information has been amended from the previous report.

Last Revised: January 31, 2022

[1] Department of the Treasury, “Treasury’s Portal for Recipient Reporting State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds,” FAQ #1.11, at 29, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF_Treasury-Portal-Recipient-Reporting-User-Guide.pdf.

[2] Department of Treasury, “Project and Expenditure Report User Guide State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds” (as of January 24, 2022), FAQ #1.14, at 84, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/Project-and-Expenditure-Report-User-Guide.pdf.

[3]Id., at 7.

[4]Id., at 84.

[5] See information regarding the deadlines for reporting under U.S. Department of the Treasury, Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds—Compliance and Reporting Guidance, Version 2.1, November 15, 2021, at 13, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Compliance-and-Reporting-Guidance.pdf.

[6] Department of the Treasury, “Treasury’s Portal for Recipient Reporting State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds,” FAQ #3.1, at 31, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF_Treasury-Portal-Recipient-Reporting-User-Guide.pdf.

Program

COVID-19 Federal Assistance e311Topics

Program AdministrationFunding Source

American Rescue Plan ActCan a municipality that charges property owners an annual Sewer and Storm Water Fee use ARP funds to pay for sewer and stormwater capital projects?

Under the U.S. Department of the Treasury's (“Treasury”) Final Rule, the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds ("CSLFRF"), established by the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (“ARP”), includes support to municipalities for water and sewer infrastructure projects and services.[1] Treasury’s Final Rule provided increased “flexibilities and simplifications,” including for water and sewer infrastructure.[2] Treasury guidance indicates that in specific scenarios, a municipality that charges an annual sewer and stormwater fee (that is not ad valorem property tax) is permitted to utilize CSLFRF to “finance the generation and delivery of clean power to a wastewater system or a water treatment plant on a pro-rata basis.”[3]

Regarding the use of CSLFRF for sewer and stormwater capital projects, Treasury outlines the “eligible use categories for water and sewer infrastructure” in the Final Rule.[4]

The Final Rule explicitly states that it has:

aligned eligible uses of the [CSLFRF] with the wide range of types or categories of projects that would be eligible to receive financial assistance through the Clean Water State Revolving Fund (CWSRF) or Drinking Water State Revolving Fund (DWSRF) administered by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). By referring to these existing programs, with which many recipients are already familiar, Treasury intended to provide flexibility to recipients to respond to the needs of their communities while facilitating recipients’ identification of eligible projects.[5]

It is important to note that the Final Rule maintains the references to the CWSRF and DWSRF and reflects “a revised standard for determining a necessary water and sewer infrastructure investment for eligible water and sewer uses beyond those uses that are eligible under the DWSRF and CWSRF.”[6]

Under the Clean Water State Revolving Fund and the Final Rule, Treasury identifies a variety of eligible projects, including:

- Construction of publicly owned treatment works;

- Projects pursuant to implementation of a nonpoint source pollution management program established under the Clean Water Act (CWA);

- Decentralized wastewater treatment systems that treat municipal wastewater or domestic sewage;

- Management and treatment of stormwater or subsurface drainage water;

- Water conservation, efficiency, or reuse measures;

- Development and implementation of a conservation and management plan under the CWA;

- Watershed projects meeting the criteria set forth in the CWA;

- Energy consumption reduction for publicly owned treatment works;

- Reuse or recycling of wastewater, stormwater, or subsurface drainage water; and

- Security of publicly owned treatment works.

Treasury encourages recipients to review the EPA handbook for the CWSRF for a full list of eligibilities.[7]

In addition, under the Drinking Water State Revolving Fund and the Final Rule, Treasury identifies a variety of eligible projects such as:

- Facilities to improve drinking water quality;

- Transmission and distribution, including improvements of water pressure or prevention of contamination in infrastructure and lead service line replacements;

- New sources to replace contaminated drinking water or increase drought resilience, including aquifer storage and recovery system for water storage;

- Green infrastructure, including green roofs, rainwater harvesting collection, permeable pavement;

- Storage of drinking water, such as to prevent contaminants or equalize water demands;

- Purchase of water systems and interconnection of systems; and

- New community water systems.

Similarly, Treasury encourages recipients to review the EPA handbook for the DWSRF for a full list of eligibilities.[8]

For eligible water and sewer uses beyond those uses that are eligible under the DWSRF and CWSRF, Treasury has explicitly identified these additional eligible projects:

- Culvert repair, resizing, and removal, replacement of storm sewers, and additional types of stormwater infrastructure;

- Infrastructure to improve access to safe drinking water for individual[s] served by residential wells, including testing initiatives, and treatment/remediation strategies that address contamination;

- Dam and reservoir rehabilitation if primary purpose of dam or reservoir is for drinking water supply and project is necessary for provision of drinking water; and

- Broad set of lead remediation projects eligible under EPA grant programs authorized by the Water Infrastructure Improvements for the Nation (WIIN) Act, such as lead testing, installation of corrosion control treatment, lead service line replacement, as well as water quality testing, compliance monitoring, and remediation activities, including replacement of internal plumbing and faucets and fixtures in schools and childcare facilities.[9]

Additionally, Treasury has outlined a non-exclusive range of eligible uses for water and sewer infrastructure which include those deemed “[a] ‘necessary’ investment in infrastructure” that must be:[10]

(1) responsive to an identified need to achieve or maintain an adequate minimum level of service, which may include a reasonable projection of increased need, whether due to population growth or otherwise;

(2) a cost-effective means for meeting that need, taking into account available alternatives; and

(3) for investments in infrastructure that supply drinking water in order to meet projected population growth, projected to be sustainable over its estimated useful life.[11]

To determine if intended funding uses are permissible or deemed "a 'necessary' investment in infrastructure," a municipality should generally refer to the Clean Water State Revolving Funds Program Eligibilities for sewer and stormwater projects along with the enumerated eligible uses provided above.[12], [13]

Regarding the use of CSLFRF for new, energy-related projects, Treasury’s FAQs state:

The EPA's Overview of Clean Water State Revolving Fund Eligibilities describes eligible energy-related projects. This includes a "[p]ro rata share of capital costs of offsite clean energy facilities that provide power to a treatment works." Thus, State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds may be used to finance the generation and delivery of clean power to a wastewater system or a water treatment plant on a pro-rata basis.[14]

If a municipality's annual sewer and stormwater fee covered the cost of delivering or facilitating clean power to a wastewater system or water treatment plant, or if the municipality sought to maintain or expand its clean energy systems to deliver more power to a wastewater system or water treatment plant, then as provided above, the Treasury guidance indicates that these expenses would likely be permissible uses of CSLFRF on a pro-rata basis.

A municipality should also review its State Revolving Funds ("SRFs") to help inform the municipality's strategy. Treasury states "the [Rule] does not incorporate any other requirements contained in the federal statutes governing the SRFs or any conditions or requirements that individual states may place on their use of SRFs."[15] This remains evident with the Final Rule's release, as Treasury has not explicitly stated otherwise.

A municipality that charges an annual sewer and stormwater fee that is not ad valorem property tax should also focus on the risk of potential duplication of benefits ("DOB"). DOB occurs if a person, household, business, government, or other entity receives financial assistance from multiple sources for an identical purpose, and the total aid received for that purpose, therefore, exceeds the total need for assistance. Municipalities should conduct a DOB analysis to determine which costs have not been paid from another assistance fund source to avoid duplication.

Recipients may use CSLFRF funds to cover costs incurred for eligible sewer and water-related projects that have been "planned or started prior to March 3, 2021, provided these project costs are covered by the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds and were incurred after March 3, 2021."[16] Notably, Treasury states in the Final Rule that it:

is also maintaining the deadlines by which funds must be obligated (i.e., December 31, 2024) and by which such obligations must be liquidated (i.e., December 31, 2026). The December 31, 2024 deadline by which eligible costs must be incurred is established by statute. Treasury is finalizing its interpretation of "incurred" to be equivalent to the definition of "obligation," based on the definition used for purposes of the Uniform Guidance. Treasury is also maintaining the period of performance, which will run through December 31, 2026, and provides the deadline by which recipients must expend obligated funds.[17]

Notably, Treasury is expected to issue new Frequently Asked Questions ("FAQs") specific to the Final Rule, which could provide further guidance on the subject.[18] In addition, Treasury encourages municipalities to consider the guidance issued in the Statement Regarding Compliance with the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds Interim Final Rule and Final Rule.[19]

Last Updated: March 11, 2022

[1] Treas. Reg. 31 CFR Part 35 at 5, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Final-Rule.pdf.

[2] Department of Treasury, Coronavirus State & Local Fiscal Recovery Funds: Overview of the Final Rule, (as of January 2022), at 5, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Final-Rule-Overview.pdf.

[3] Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, Frequently Asked Questions (as of January 2022) – FAQ #6.13, at 32, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRPFAQ.pdf.

[4] Treas. Reg. 31 CFR Part 35 at 265-293, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Final-Rule.pdf.

[5] Id., at 265.

[6] Treas. Reg. 31 CFR Part 35 at 265, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Final-Rule.pdf.

[7] Department of Treasury, Coronavirus State & Local Fiscal Recovery Funds: Overview of the Final Rule, (as of January 2022), at 37, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Final-Rule-Overview.pdf.

[8] Id.

[9] Id., at 38.

[10] Id.

[11] Id.

[12] Id.

[13] U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Overview of Clean Water State Revolving Fund Eligibilities, May 2016, at 3, available at: https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/201607/documents/overview_of_cwsrf_eligibilities_may_2016.pdf.

[14] Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, Frequently Asked Questions (as of January 2022) – FAQ #6.13, at 32, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRPFAQ.pdf.

[15] Id., at FAQ #6.7, at 29.

[16] Id., at FAQ #4.7, at 21.

[17] Treas. Reg. 31 CFR Part 35 at 357, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Final-Rule.pdf.

[18] Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, Frequently Asked Questions (as of January 2022), at 1, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRPFAQ.pdf.

[19] U.S. Department of the Treasury, Statement Regarding Compliance with the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds Interim Final Rule and Final Rule, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Compliance-Statement.pdf.

Program

COVID-19 Federal Assistance e311Topics

Due Diligence & Fraud ProtectionFunding Source

American Rescue Plan Act, CARES Act, FEMA, HUD, Infrastructure Investments and Jobs ActWhat good practices can municipalities follow to minimize duplicative work and stay current with changing reporting requirements?

There are many good practices for municipalities to implement to ensure they minimize duplicative work and stay current with reporting requirements for both the American Rescue Plan Act’s (“ARP”) Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Fund (“CSLFRF”) and the Coronavirus Aid Relief and Economic Security Act’s (“CARES Act”) Coronavirus Relief Fund (“CRF”).[1]

First, municipalities should choose to designate representatives who can: (i) track deadlines; (ii) monitor newly published guidance and regulations; and (iii) share the relevant information with internal representatives and external stakeholders. The U.S. Department of the Treasury (“Treasury”) has published information relating specifically to CSLFRF “Recipient Compliance and Reporting Responsibilities” on its website.[2]

To ensure compliance with the reporting guidance discussed further below, municipalities should: (i) review their procurement procedures to ensure compliance with federal and other relevant mandates; (ii) take steps to ensure compliance with relevant documentation mandates; and (iii) implement ongoing training to facilitate compliance with the numerous applicable federal, state, and local mandates.

Documentation

Reporting requirements for federal grants have many similarities, including quarterly expenditure reports and detailed procurement processes. The CSLFRF and the CRF vary in their respective reporting requirements.

Reporting obligations for the CRF are detailed in a memorandum prepared by the Treasury Office of Inspector General (“OIG”).[3] Pursuant to CSLFRF, municipalities must provide quarterly project and expenditure reports relating to their use of CSLFRF funds.[4] CSLFRF reporting obligations are also reported in the Interim Final Rule,[5] the Final Rule,[6] and several of Treasury’s Frequently Asked Questions (“FAQs”) relating to the CSLFRF.[7]

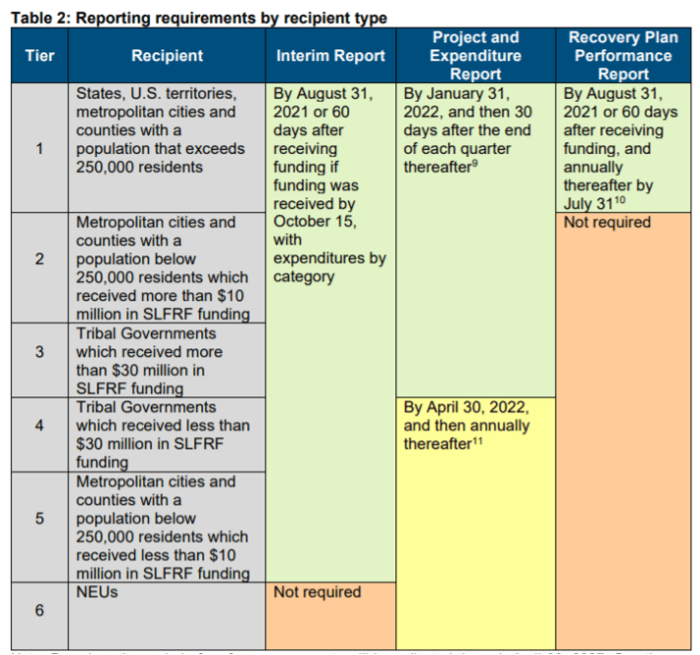

The below chart provides important information about Treasury reporting deadlines for recipients of CSLFRF.[8]

In order to assist municipalities in submitting the Project and Expenditure Report due on January 31, 2022, and subsequent Recovery Plan Performance Reports, Treasury published the following information:

- Recipient Reporting User Guide, to assist municipalities with the submission of the Recovery Plan Performance Reports.[9]

- Recovery Plan Performance Report Template, posted on Treasury’s Recipient Compliance and Reporting Guidance webpage.

- CSLFRF Compliance and Reporting Guidance, which provides details and clarification for each recipient’s compliance and reporting responsibilities.[10]

Municipalities should stay up-to-date on guidance and FAQs published by Treasury and other federal agencies, including changes to the reporting requirements. For the CSLFRF programs, municipalities can stay current by registering on Treasury’s website[11] to receive email updates on changes to the FAQs.

Below are examples of additional guidance and published FAQs that are helpful in understanding reporting and documentation requirements:

- July 19, 2021, Treasury Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds Frequently Asked Questions[12]

- April 19, 2021, Treasury Office of Inspector General - Coronavirus Relief Fund Prime Recipient Quarterly GrantSolutions Submissions Monitoring and Review Procedure Guide[13]

- March 10, 2021, Treasury Interim Final Rule, Section VIII “Reporting”[14]

- March 2, 2021, Office of Inspector General Coronavirus Relief Fund Frequently Asked Questions Related to Reporting and Recordkeeping[15]

- July 2, 2020, Treasury Office of Inspector General - Coronavirus Relief Fund Reporting and Record Retention Requirements[16]

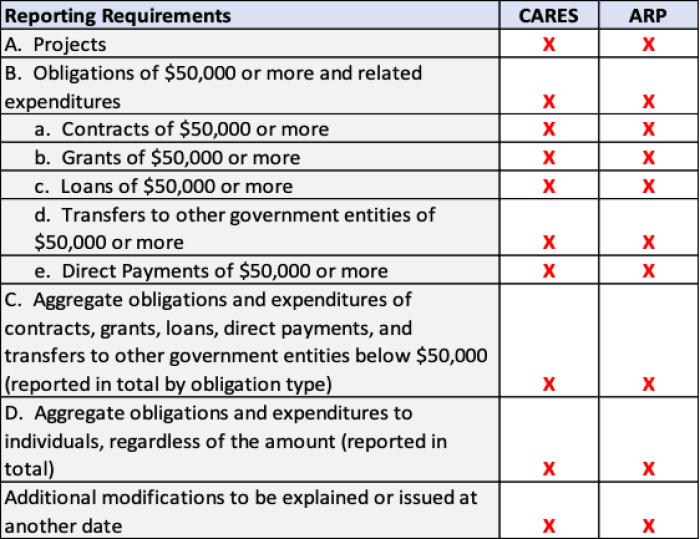

The table below shows many of the overlapping reporting requirements for the CARES Act[17] and ARP[18] that municipalities must provide in quarterly reports.[19]

Although municipalities are required to report similar information for both funding sources, records should be maintained separately, and attention should be given to the good practices described below for documenting the projects and expenditure reports. Adhering to good practices in documenting the information for use in CRF and CSLFRF reports will help facilitate transparency and proper accounting for expenditures. Robust documentation will also help prepare the municipality for any additional city, state, or federal reporting obligations or audits.

In April 2021, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (“FEMA”) released a fact sheet on Audit-Related Guidance for Entities Receiving FEMA Public Assistance Funds.[20] Following these recommendations can help municipalities meet federal reporting requirements as well as other reporting requirements that may be required by municipalities or states. The recommendations require a municipality to::

- Designate a person to coordinate the accumulation of records (e.g., receipts, invoices, etc.).

- Establish a separate and distinct account for recording revenue and expenditures and a separate identifier for each distinct FEMA project.

- This process can also be used for separating CRF and CSLFRF funds and the individual projects within each.

- Ensure that the final expenditures for each project are supported by the dollar amounts recorded within the accounting system of record.

- Ensure that each expenditure is recorded and linked to supporting documentation (e.g., checks, invoices, etc.) that can be easily retrieved.

- Ensure that expenditures claimed are necessary to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, reasonably pursuant to federal regulations and federal cost principles and conform to standard program eligibility and other federal requirements.[21]

Additional steps that a municipality may consider in helping to manage the similar reporting requirements of the two programs:

- Implement a uniform reporting format for both CRF funds and CSLFRF funds to allow for easy data transference between sub-recipient and prime recipient and between prime recipient and reporting platform.

- Prepare project documents as if already under audit by creating an audit trail that a municipality will be able to rely on should an audit happen immediately. The audit trail should include, but not necessarily be limited to, general ledgers that account for the receipt and disbursement of funds, budget records for 2019, 2020, and 2021 payroll records to support payroll expenses related to COVID-19, contracts and subcontracts, and, where applicable, photographs supporting expenditures.

- Leverage technology solutions to generate multiple reports with the same data points for various governing entities, where applicable.

- Continually audit project documents for accuracy and adherence to reporting guidelines.

- Ensure that both prime recipient and sub-recipients have valid DUNS numbers and have active SAM registrations to minimize reporting time.

- According to OIG-CA-21-020 (“American Rescue Plan – Application of Lessons Learned from the Coronavirus Relief Fund”), issued by the Treasury on May 10, 2021, “Treasury officials are considering various software options for ARP recipient reporting and administration, including GrantSolutions and Salesforce.”[22]

- Municipalities can prepare for CSLFRF reporting by ensuring that those expected to receive this assistance are registered with SAM and have valid DUNS numbers.

Resources such as Bloomberg’s COVID e311 repository[23] provide additional information on updated timelines, requirements, and comparisons for documentation overlap between CARES and ARP. Some examples include:

- What are good practices for documenting and accounting for programs using federal funds? | Bloomberg Cities (jhu.edu)

- What documentation is a municipality required to supply in order to receive funds? What is the due date for the documentation? | Bloomberg Cities (jhu.edu)

- How are reporting requirements impacted by a city’s fiscal calendar? | Bloomberg Cities (jhu.edu)

To facilitate documentation accuracy, municipalities should consider implementing a robust policy or decision checklist to ensure that eligible expenses meet the definitions of use by the particular grant/award. It may be helpful for multiple personnel to participate in the evaluation process, using the same criteria as provided by each funding type, to confirm that the expenses meet the outlined priorities of the federal funds.

Procurement Processes

Substantial federal guidance is available regarding the procurement process and requirements. First, municipalities should review the eligible and ineligible uses of ARP funds published in the Final Rule.[24] Second, the FEMA “Top 10 Procurement under Grants Mistakes” highlights key risks applicable to all contracting using federal grant assistance.[25] Third, 2 CFR Part 200 contains mandates relating to Uniform Administrative Requirements, Cost Principles, and Audit Requirements for Federal Awards.[26] 2 CFR Part 200 provides recipients with mandates relating to the use of federal grant assistance. The mandates of this regulation are also addressed in Part 1(D) of Treasury’s Compliance and Reporting Guidance.[27] 2 CFR 200 applies to all federal programs; therefore, recipients should be familiar with it.

Fourth, just as the federal government details procurement processes, each government entity (such as a municipality) or other recipients or subrecipients of CSLFRF assistance should have written policies delineating required steps for contracting. In some cases, municipalities may find it prudent or expedient to mirror state processes. If there are no standardized written procurement policies at the municipal level, the adoption of state rules can help municipalities implement proper procurement procedures for the use of CSLFRF assistance. Strict compliance with local, state, and federal procurement requirements will reduce the risk of future negative audit findings.

Non-Entitlement Units (“NEUs”) are local governments typically serving a population under 50,000. For NEUs requesting CSLFRF funding, the Treasury Checklist for Requesting Initial Payment[28] includes general “After Requesting Funding”[29] information that may assist the planning process even before spending begins.

Municipalities can also use resources such as the FEMA Fact Sheet[30] for guidance on preparatory steps and best practices designed to “overlay” applicable state and municipal procurement practices onto the federal procurement rules for these funds.

Ongoing Training

While procurement processes and documentation requirements target a particular grant's objectives and eligible expenses, financial management training can help improve government operations. In addition to educating employees on specific provisions of the CSLFRF and CRF, municipalities can also use learning opportunities to develop skills and preparedness for general disaster recovery and related funding procedures. Various topics are offered via online self-study and in classroom settings, all tailored to fit the post-pandemic work environment. Types of training that improve general operations and are not strictly related to COVID-19 funding include:

- fraud awareness;

- grant program-specific training;

- electronic portal training specific to federal program;

- intra-agency working groups; and

- technology solutions that would help financial tracking and documentation management.

The FEMA National Preparedness Course Catalog can be searched to identify relevant trainings or courses that may be beneficial to municipalities.[31]

Certain federal government departments and regional offices that oversee programs like the CRF and CSLFRF, as well as FEMA’s Public Assistance (“PA”) and Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (“HMGP”) also provide free trainings. Training modules should be scheduled as reporting requirements change to ensure all employees responsible for such programs are notified of changes and can adapt programs as needed.

Recipients should regularly check the following agency pages to find out when technical assistance webinars are being scheduled:

- Department of Treasury CSLFRF

- Department of Treasury Emergency Rental Assistance Program

- FEMA PA for COVID-19

- FEMA HMGP:

Furthermore, some national, non-governmental organizations provide training and educational resource libraries on various aspects of CRF and CSLFRF funding for both states and municipalities:

- The United States Conference of Mayors: Organization of cities with populations of 30,000 or more. The conference and its members (elected mayors) develop policies and programs that collectively represent the views of members. Resources and programs are available on their website, including a dedicated section on COVID-19 issues and ARP Resources for cities.[32]

- National Association of Counties (“NACo”): Serves nearly 40,000 county elected officials and 3.6 million county employees through membership services, including education and events.[33] On-demand educational series include “Understanding Eligible Uses of the Fiscal Recovery Fund.”[34]

- National League of Cities (“NLC”): Serves more than 2,000 cities across the United States and has a dedicated library of over 100 COVID-19 related resources including a forum to connect with other cities, FAQ forms, and webinars on updates to Treasury guidance.[35]

- National Association of State Budget Officers (“NASBO”): Monitors budget and financial implications related to COVID-19 and provides weekly updates in their Washington Report e-publication.[36] Municipal officials can subscribe to the Washington Report for weekly updates on financial and budgetary details of ARP and other COVID-19-related funding questions.[37]

- National Governors Association (“NGA”): Represents leaders from 55 states, territories, and commonwealths and provides dedicated COVID-19 updates on their website.[38] Resources include an ARP eligibility guide, webinars, and publications.[39]

- National Association of State Auditors, Comptrollers, and Treasurers (“NASACT”): Works to address government financial management issues and has a dedicated COVID-19 resource library for state governments.[40]

- National Conference of State Legislatures (“NCSL”): Aims to facilitate exchange of information between legislatures in states, territories, and commonwealths and provides a dedicated COVID-19 database of resources for states.[41] The fiscal section in the database includes a state-by-state breakdown of ARP funding.[42]

- Government Finance Officers Association (“GFOA”): Represents public finance officials throughout the United States and hosts weekly educational events and webinars to educate municipal officials on Treasury updates and other government finance topics.[43] Additionally, GFOA provides a Coronavirus Response Resource Center with information on the CARES Act and CSLFRF.[44]

- National Emergency Management Association (“NEMA”): Supports the professionalization of emergency management and aims to strengthen the nation’s emergency management system.[45]

Last Revised: January 31, 2022

[1] American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 § 9901, Pub. L. No. 117-2, amending 42 U.S.C. § 801 et seq., available at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/1319/text#HAECAA3A95C4E4FFAB6AA46CE5F9CB2B5. See also Coronavirus Aid, Relief, Economic Security Act (CARES Act), Pub. L. No. 116–136, 134 Stat. 281 (2020), available at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/748/text.\.

[2] U.S. Department of the Treasury, Recipient Compliance and Reporting Responsibilities, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/policy-issues/coronavirus/assistance-for-state-local-and-tribal-governments/state-and-local-fiscal-recovery-funds/recipient-compliance-and-reporting-responsibilities.

[3] U.S. Department of the Treasury Office of Inspector General, “Memorandum for Coronavirus Relief Fund Recipients”, July 2, 2020, 1-3, https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/IG-Coronavirus-Relief-Fund-Recipient-Reporting-Record-Keeping-Requirements.pdf.

[4] U.S. Department of Treasury, Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds—Compliance and Reporting Guidance, Version, 2.1, November 15, 2021, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Compliance-and-Reporting-Guidance.pdf. See also U.S. Department of the Treasury, Treasury’s Portal for Recipient Reporting, State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF_Treasury-Portal-Recipient-Reporting-User-Guide.pdf.

[5] Treas. Reg. 31 CFR Part 35 at 110-112, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/FRF-Interim-Final-Rule.pdf.

[6] Treas. Reg.31 CFR Part 35, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Final-Rule.pdf.

[7] Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds Frequently Asked Questions (as of July 19, 2021), at 34-37, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRPFAQ.pdf.

[8] U.S. Department of Treasury, Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds—Compliance and Reporting Guidance, Version, 2.1, November 15, 2021, at 13, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Compliance-and-Reporting-Guidance.pdf.

[9] U.S. Department of the Treasury, Treasury’s Portal for Recipient Reporting, August 9, 2021, available at https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF_Treasury-Portal-Recipient-Reporting-User-Guide.pdf.

[10] U. S. Department of Treasury, Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds—Compliance and Reporting Guidance, Version, 2.1, November 15, 2021, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Compliance-and-Reporting-Guidance.pdf.

[12] Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds Frequently Asked Questions (as of July 19, 2021), available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRPFAQ.pdf.

[13] Coronavirus Relief Fund Prime Recipient Quarterly GrantSolutions Submissions Monitoring and Review Procedure Guide, April 19, 2021, available at: https://oig.treasury.gov/sites/oig/files/2021-04/OIG-CA-20-029R.pdf.

[14] Treas. Reg. 31 CFR 35 at 110-112, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/FRF-Interim-Final-Rule.pdf.

[15] Treasury Office of Inspector General, Coronavirus Relief Fund Frequently Asked Questions Related to Reporting and Recordkeeping, March 2, 2021, available at: https://bfm.sd.gov/covid/OIG_CRF_FAQ_20210302.pdf.

[16] Treasury Office of Inspector General, Coronavirus Relief Fund Reporting and Record Retention Requirements, July 2, 2020, available at: https://oig.treasury.gov/sites/oig/files/2021-01/OIG-CA-20-021.pdf.

[17] U.S. Department of the Treasury, Department of the Treasury Office of Inspector General Coronavirus Relief Fund Frequently Asked Questions Related to Reporting and Recordkeeping (Revised), March 2, 2021, at Question #40, at 10-11, available at: https://bfm.sd.gov/covid/OIG_CRF_FAQ_20210302.pdf.

[18] Treas. Reg. 31 CFR 35 at 110-112, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/FRF-Interim-Final-Rule.pdf.

[19] Note that according to the Treasury Interim Final Rule, pg. 111, aside from quarterly reports, each municipality that is not considered a “nonentitlement unit of local government” will have to provide an interim report from the date of award to July 31, 2021. Nonentitlement units of local governments are required to provide Project and Expenditure annual reports rather than quarterly reports. These reports follow the same guidelines as in the table below.

[20] FEMA, Audit-Related Guidance for Entities Receiving FEMA Public Assistance Funds, April 6, 2021, available at: https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/documents/fema_audit-related-guidance-entities-receiving_public-assistance_4-6-2021.pdf.

[21] Id., at 1-2.

[22] U.S. Department of the Treasury, OIG-CA-21-2020, American Rescue Plan – Application of Lessons Learned from the Coronavirus Relief Fund, May 17, 2021, at 6, available at: https://oig.treasury.gov/sites/oig/files/2021-05/OIG-CA-21-020.pdf.

[23] Bloomberg Cities Network, “Federal Assistance e311 Knowledge Base,” available at: https://bloombergcities.jhu.edu/program/e311/knowledge-base.

[24] Treas. Reg. 31 CFR 35 at 138-145, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/FRF-Interim-Final-Rule.pdf ; Treas. Reg. 31 CFR 35 at 12, available at https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Final-Rule.pdf ; U.S. Department of the Treasury, Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds Fact Sheet as of May 10, 2021, at 2-8, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRP-Fact-Sheet-FINAL1-508A.pdf; 31 CFR Part 35, Final Rule, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Final-Rule.pdf.

[25] FEMA, Top Ten Procurement under Grants Mistakes, available at: https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/2020-08/fema_top-10-mistakes_flyer.pdf.

[26] 2 CFR § 200, available at: https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/2/part-200.

[27] U.S. Department of the Treasury, Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds—Compliance and Reporting Guidance, Version, 2.1, November 15, 2021, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Compliance-and-Reporting-Guidance.pdf.

[28] U.S. Department of the Treasury, Coronavirus Local Fiscal Recovery Fund: Non-entitlement Unit of Local Government Checklist for Requesting Initial Payment, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/NEU_Checklist_for_Requesting_Initial_Payment.pdf.

[29] Id.

[30] FEMA, Audit-Related Guidance for Entities Receiving FEMA Public Assistance Funds, April 6, 2021, available at: https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/documents/fema_audit-related-guidance-entities-receiving_public-assistance_4-6-2021.pdf.

[31] FEMA, National Preparedness Course Catalog, available at: https://www.firstrespondertraining.gov/frts/npccatalog?catalog=EMI.

[32] The United States Conference of Mayors, COVID-19: What Mayors Need to Know, available at: https://www.usmayors.org/issues/covid-19/.

[33] National Association of Counties, NACo Knowledge Network, available at: https://www.naco.org/education-events#on-demand.

[34] Id.

[35] National League of Cities, Resource Library, available at: https://www.nlc.org/resources-training/resource-library/?orderby=date&topic%5B%5D=covid-19.

[36] National Association of State Budget Officers, COVID-19 Relief Funds Guidance and Resources, available at: https://www.nasbo.org/mainsite/resources/covid-19-relief-funds-guidance-and-resources.

[37] National Association of State Budget Officers, Washington Report, available at: https://www.nasbo.org/resources/e-publications/washington-report.

[38] National Governors Association, COVID-19: What you need to know, available at: https://www.nga.org/coronavirus/.

[39] National Governors Association, NGA Issue Library, available at: https://www.nga.org/library/?tx_post_tag=coronavirus-posts.

[40] National Association of State Auditors, Comptrollers, and Treasurers, COVID-19 Resources for States, available at: https://www.nasact.org/covid_19_resources_for_states.

[41] National Conference of State Legislatures, NCSL Coronavirus (COVID-19) Resources for States, available at: https://www.ncsl.org/research/health/ncsl-coronavirus-covid-19-resources.aspx.

[42] Id.

[43] Government Finance Officers Association, Events Calendar, available at: https://www.gfoa.org/events.

[44] Government Finance Officers Association, Coronavirus Response Resource Center, available at: https://www.gfoa.org/coronavirus.

[45] National Emergency Management Association, NEMA Resources, available at: https://www.nemaweb.org/index.php/resources#webinars.

Program

COVID-19 Federal Assistance e311Topics

Lost Revenue & Revenue ReplacementFunding Source

American Rescue Plan ActCan ARP funds from revenue loss calculations serve as a match to other federal programs like traditional municipal dollars?

The U.S. Department of the Treasury’s (“Treasury”) Final Rule on Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (“CSLFRF”) states, “…the funds available under sections 602(c)(1)(C) and 603(c)(1)(C) of the Social Security Act for the provision of government services, up to the amount of the recipient’s reduction in revenue due to the public health emergency, generally may be used to meet the non-federal cost-share or matching requirements of other federal programs.”[1]

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (“IIJA”) amends sections 602(c) and 603(c) of the Social Security Act to include an additional eligible use of CSLFRF used to satisfy non-federal match requirements:

This amendment permits the use of [CSLFRF] funds to meet non-federal matching requirements of any authorized Bureau of Reclamation project, regardless of whether the underlying project would be an eligible use of [CSLFRF] funds under the water and sewer infrastructure eligible use category.[2]

Treasury clarifies that further guidance will be provided to award recipients on the scope and covered expenses of such projects.[3] Further, under section 60102 of the IIJA, American Rescue Plan (“ARP”) funds may be used to meet the non-federal match requirements of the broadband infrastructure program authorized under that section.[4]

Treasury has also enumerated ineligible uses of CSLFRF funds serving as non-federal match:

[CSLFRF] funds may not be used as the non-federal share for purposes of a state’s Medicaid and CHIP programs because the Office of Management and Budget has approved a waiver as requested by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services pursuant to 2 CFR 200.102 of the Uniform Guidance and related regulations.[5]

Prior to using CSLFRF awards to satisfy non-federal match requirements, Treasury states that award recipients should:

[1] confirm with the relevant awarding agency that no waiver has been granted for that program, [2] that no other circumstances enumerated under 2 CFR 200.306(b) would limit the use of SLFRF funds to meet the match or cost-share requirement, and [3] that there is no other statutory or regulatory impediment to using the SLFRF funds for the match or cost-share requirement.[6]

CSLFRF funds beyond those available for the provision of government services may not be used to meet the non-federal match or cost-share requirements of other federal programs other than as expressly provided for by statute.[7]

Recipients should consider all compliance and reporting requirements enumerated in the Uniform Guidance[8] and Treasury’s Compliance and Reporting Guidance[9] before using funds for non-federal match purposes. Notably, Treasury’s Compliance and Reporting Guidance has included language regarding matching in Section 6:

There are no matching, level of effort, or earmarking compliance responsibilities associated with the [CSLFRF] award…[CSLFRF] funds may only be used for non-Federal match in other programs where costs are eligible under both [CSLFRF] and the other program and use of such funds is not prohibited by the other program.[10]

Last Revised: February 20, 2022

[1] Treas. Reg. 31 CFR 35 at 368, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Final-Rule.pdf.

[2] Id., at 291.

[3] Id.

[4] See Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, Pub. L. No. 117-58 (2021), at 1198, available at: PUBL058.PS (congress.gov).

[5] Treas. Reg. 31 CFR 35 at 369, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Final-Rule.pdf.

[6] Id.

[7] Id.

[8] 2 CRF Part 200, Uniform Guidance Subpart D, available at: eCFR :: 2 CFR Part 200 -- Uniform Administrative Requirements, Cost Principles, and Audit Requirements for Federal Awards.

[9] Department of Treasury, Compliance and Reporting Guidance: State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, (as of November 15, 2021), available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Compliance-and-Reporting-Guidance.pdf.

[10] Id., at 8.

Program

COVID-19 Federal Assistance e311Topics

Timing of FundsFunding Source

American Rescue Plan ActAre payroll costs for public health, safety, and other public sector staff responding to COVID-19 incurred prior to March 3, 2021, eligible for reimbursement through the CSLFR grant?

The U.S. Department of the Treasury ("Treasury") Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds ("CSLFRF") Final Rule specifies that Fiscal Recovery Funds cannot be used for expenses incurred prior to March 3, 2021.[1] This includes payroll costs for public health, safety, and other public sector staff responding to the COVID-19 public health emergency.

According to the Final Rule:

Treasury is maintaining March 3, 2021 as the date when recipients may begin to incur costs using [CSLFRF] funds. As described in the interim final rule, use of [CSLFRF] funds is forward looking and the eligible use categories provided by statute are all prospective in nature. While recipients may identify and respond to negative economic impacts that occurred during 2020, the costs incurred to respond to these impacts remain prospective.[2]

The Final Rule further explains that March 3, 2021, is maintained as the beginning of the covered period in order to determine compliance and provide flexibility for those recipients who began incurring costs in anticipation of ARP. Treasury states that an earlier date would leave recipients vulnerable to spending funds on uses other than what is eligible for CSLFRF.[3]

It may therefore be helpful for municipalities to explore other funding sources to reimburse relevant costs incurred prior to March 3, 2021. Other funding sources may include Federal Emergency Management Agency (“FEMA”) Public Assistance[4] or funding through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (“CARES Act”) Coronavirus Relief Fund (“CRF”),[5] which impose less restrictive timelines on eligible expense.

Last Revised: February 16, 2022

[1] Treas. Reg. 31 CFR 35 at 11, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Final-Rule.pdf.

[2] Id., at 356.

[3] Id., at 356-357.

[4] Public Assistance Disaster-Specific Guidance - COVID-19 Declarations | FEMA.gov, available at https://www.fema.gov/media-collection/public-assistance-disaster-specific-guidance-covid-19-declarations.

[5] Coronavirus Relief Fund | U.S. Department of the Treasury, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/policy-issues/coronavirus/assistance-for-state-local-and-tribal-governments/coronavirus-relief-fund.

Program

COVID-19 Federal Assistance e311Topics

Lost Revenue & Revenue ReplacementFunding Source

American Rescue Plan ActAfter the revenue loss amount has been calculated, is it permissible to use funds for expenses incurred prior to March 3, 2021?

The U.S. Department of the Treasury’s (“Treasury”) American Rescue Plan Act (“ARP”) Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (“CSLFRF”) Final Rule states that ARP funds may only be used for costs incurred within a specific time period, beginning March 3, 2021, with all funds obligated by December 31, 2024 and all funds spent by December 31, 2026.[1] Municipalities may not use CSLFRF funds to cover costs incurred prior to March 3, 2021.[2]

As specified in the Final Rule, municipalities must employ a “forward-looking” approach to use CSLFRF. The Final Rule states:

Treasury will retain March 3, 2021 as the first date when costs may be incurred, to provide for forward-looking or prospective use of funds and to align with the start date of the “covered period” as such term is used in section 602(c)(2)(A). The deadline for costs to be incurred – which the final rule clarifies means obligated – December 31, 2024, is specified in the ARPA statute, and Treasury will retain December 31, 2026 as the end of the period of performance to provide a reasonable amount of time for recipients to liquidate obligations incurred by the statutory deadline.[3]

However, while a municipality may only use CSLFRF to cover expenses incurred on or after March 3, 2021, costs for eligible infrastructure projects that were started prior to March 3, 2021, as well as assistance to households and retroactive premium pay, may be eligible so long as the recipient incurred the costs to which CSLFRF is being applied after March 3, 2021.[4] It should be noted that additional information may be provided when Treasury issues a new Frequently Asked Questions ("FAQ") specific to the Final Rule, as indicated in the Interim Final Rule FAQ updated simultaneously with the issuance of the Final Rule.[5]

Municipalities may wish to examine Federal Emergency Management Agency (“FEMA”) Public Assistance (“PA”) program as an alternative for certain COVID-related expenses incurred prior to March 3, 2021. As of November 9, 2021, the White House extended FEMA’s 100% reimbursement for COVID emergency protective measures and extended COVID Title 32 authorization at 100% cost share through April 1, 2022. This allows for retroactive 100% reimbursement of costs for eligible safe-opening and operations work prior to January 2021 (back to January 20, 2020), thus providing additional opportunities for expense reimbursement through PA funds.[6]

Last Revised: January 31, 2022

[1] Treas. Reg. 31 CFR 35 at 11, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Final-Rule.pdf.

[2] Id.

[4] Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, Frequently Asked Questions (as of January 2022) – FAQ #4.7, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRPFAQ.pdf.

[5] Id.

[6] The White House, “Memorandum on Maximizing Assistance to Respond to COVID-19,” available at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/08/17/memorandum-on-maximizing-assistance-to-respond-to-covid-19/.

Program

COVID-19 Federal Assistance e311Topics

Housing & Rental AssistanceFunding Source

American Rescue Plan ActCan a municipality use American Rescue Plan (“ARP”) dollars to establish and fund a land bank program whose objective is to convert city-owned properties within a QCT into affordable housing?

Guidance issued by the U.S. Department of the Treasury (“Treasury”) indicates that affordable housing projects within the bounds of a Qualified Census Tract (“QCT”) likely qualify as an allowable use of ARP Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (“CSLFRF”). Municipalities have broader discretion as to how they employ CSLFRF for projects within the bounds of a QCT. Further, Treasury guidance indicates that each municipality may assess whether a land bank’s particular operations qualify as housing services that meet the eligibility requirements of the ARP.[1]

Treasury’s Final Rule released on January 6, 2022, specifies the following services for vacant or abandoned properties, which are eligible to address the public health and negative economic impacts of the pandemic on disproportionately impacted households or communities:

- Rehabilitation, renovation, maintenance, or costs to secure vacant or abandoned properties to reduce their negative impact;

- Costs associated with acquiring and securing legal title of vacant or abandoned properties and other costs to position the property for current or future productive use;

- Removal and remediation of environmental contaminants or hazards from vacant or abandoned properties, when conducted in compliance with applicable environmental laws or regulations;

- Demolition or deconstruction of vacant or abandoned buildings (including residential, commercial, or industrial buildings) paired with greening or other lot improvement as part of a strategy for neighborhood revitalization;

- Greening or cleanup of vacant lots, as well as other efforts to make vacant lots safer for the surrounding community;

- Conversion of vacant or abandoned properties to affordable housing; and

- Inspection fees and other administrative costs incurred to ensure compliance with applicable environmental laws and regulations for demolition, greening, or other remediation activities.[2]

Further, the Final Rule also clarifies that grants to a revolving loan fund, an economic development corporation, a land bank, or a similar facility must be used for costs incurred for eligible purposes no later than December 31, 2024, consistent with standard accounting practices and the Uniform Guidance.[3]

Recipients considering using CSLFRF to fund a land bank program should review the guidance provided by Treasury in the Final Rule on Vacant or Abandoned Properties to help assess eligible activities and additional considerations.[4]

In addition, CSLFRF provides opportunities for local governments to alleviate the immediate economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on housing insecurity in concentrated areas with limited economic opportunity and inadequate or poor-quality housing (such as a QCT).[5],[6] The Final Rule identifies a range of services and programs that are presumed to be eligible uses of ARP funds when provided within a QCT.[7] As a rationale for this approach, Treasury notes that “recipients can presume these uses are eligible when provided in a QCT,” and that QCTs are “a common readily-accessible and geographically granular method of identifying communities with a large proportion of low-income residents.”[8],[9]

Notably, the Final Rule states that “supportive housing and other services to improve access to stable, affordable housing among individuals who are homeless” are covered within QCTs.[10] Thus, a municipality seeking to fund a land bank with funds provided under the CSLFRF should consider structuring the land bank arrangement to support improving access to affordable housing for the homeless.

A municipality planning to implement a land bank project should undertake a thorough review of the Final Rule, particularly the sections that discuss presumptively eligible applications of funds within a QCT and consider designing their land bank’s structure and operations to satisfy those descriptions. The Center for Community Progress’ analysis provides additional guidance and good practices to consider when applying CSLFRF funds to a land bank project.[11]

Last Revised: February 1, 2022

[1] Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, Frequently Asked Questions (as of January 2022) – FAQ #2.11, at 7, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRPFAQ.pdf.

[2] Treas. Reg. 31 CFR 35 at 134, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Final-Rule.pdf.

[3] Id., at 367-368.

[4] Id., at 133.

[5] Id., at 104-105.

[6] Treas. Reg. 31 CFR 35 at 39, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/FRF-Interim-Final-Rule.pdf.

[7] Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, Frequently Asked Questions (as of January 2022) – FAQ #2.11, at 7, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRPFAQ.pdf.

[8] Treas. Reg. 31 CFR 35 at 125, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Final-Rule.pdf.

[9] Treas. Reg. 31 CFR 35 at 21, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/FRF-Interim-Final-Rule.pdf.

[10] Id., at 142.

[11] Center for Community Progress, “Community Progress Weighs in on $350 Billion ARPA State and Local Recovery Fund,” available at: https://www.communityprogress.net/blog/community-progress-weighs-treasury-arpa-350-billion-state-local-fiscal-recovery-fund.