COVID-19 Federal Assistance e311

Program

COVID-19 Federal Assistance e311Topics

Lost Revenue & Revenue ReplacementFunding Source

American Rescue Plan ActShould refunds of the prior year’s expenses be included in revenue loss calculations?

Refunds of a previous year’s expenses should not be included in the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (“CSLFRF”) revenue loss calculation.

The U.S. Department of the Treasury’s (“Treasury”) Final Rule defines “general revenue” as follows:

General revenue means money that is received from tax revenue, current charges, and miscellaneous general revenue, excluding refunds and other correcting transactions and proceeds from issuance of debt or the sale of investments, agency or private trust transactions, and intergovernmental transfers from the Federal Government, including transfers made pursuant to section 9901 of the American Rescue Plan Act.[1]

Last Revised: March 31, 2022

[1] Treas. Reg. 31 CFR Part 35 at 408, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Final-Rule.pdf.

Program

COVID-19 Federal Assistance e311Topics

Program AdministrationFunding Source

American Rescue Plan ActCan American Rescue Plan Act (“ARP”) funds be used to provide public information regarding a parks levy to improve the outdoor spaces in our community?

U.S. Department of the Treasury (“Treasury”) guidance does not indicate that Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (“CSLFRF”) can be used to provide public information for new taxes or levies within a municipality. However, a public information campaign for a parks levy may be eligible for CSLFRF funding up to the extent of revenue reduced by the COVID-19 pandemic if it constitutes a government service. Additionally, there are other ways to use CSLFRF to improve outdoor spaces in a community directly.

The municipality should take steps to understand when outreach and the dissemination of information are eligible to receive CSLFRF funding. The Final Rule describes the continued need for governments to provide public health efforts, such as public communications, to prevent and address the spread of COVID-19.[1] At first glance, a parks levy does not appear to relate directly to the prevention of COVID-19 or related public health efforts; thus, expenses related to corresponding communications likely would not be a permissible use of CSLFRF under the eligible use categories for addressing the COVID-19 emergency.

However, a public information campaign for a parks levy might be considered eligible if it qualifies as a government service to citizens. Treasury generally provides states and local governments broad latitude to use funds to provide government services. While CSLFRF guidance does not explicitly permit funding communications relating to a parks levy, the Final Rule does not explicitly preclude it. Funds can generally be used for provision of government services up to the amount of revenue lost due to the public health emergency.[2] A municipality should first perform its revenue loss calculation as set forth in Treasury guidance to determine the amount available for this use.[3] Next, a municipality should consider what constitutes a government service and the restrictions on use that apply to all uses of funds that include paying down debt or satisfying settlements or judgments:

Government services generally include any service traditionally provided by a government, unless Treasury has stated otherwise. Here are some common examples, although this list is not exhaustive:

- Construction of schools and hospitals

- Road building and maintenance, and other infrastructure

- Health services

- General government administration, staff, and administrative facilities

- Environmental remediation

- Provision of police, fire, and other public safety services (including purchase of fire trucks and police vehicles)

Government services is the most flexible eligible use category under the [CSLFRF] program, and funds are subject to streamlined reporting and compliance requirements. Recipients should be mindful that certain restrictions, which are detailed further in the Restrictions on Use section and apply to all uses of funds, apply to government services as well.[4]

If the municipality determines that communications regarding a park levy fall under the definition of “government services,” using CSLFRF funds for that purpose could be permissible. If, when reviewing the details surrounding such costs, a municipality is uncertain whether a park levy qualifies as a government service, it would be advisable to request feedback from Treasury and await further guidance.

Lastly, even if a municipality decides that costs relating to the dissemination of public information to improve outdoor spaces may not be covered by any category of CSLFRF, the improvements to the parks themselves may still be covered. Investments in improving outdoor spaces, such as parks, may be an eligible use of funds to respond to the public health emergency and/or its negative economic consequences. These investments are an enumerated use and presumed eligible when these investments serve disproportionately impacted communities.[5] Treasury encourages recipients to consider the disproportionate negative economic impacts on specific communities and populations.

Recipients may also provide these services to other populations, households, or geographic areas disproportionately impacted by the pandemic. Such programs and services include services designed to build stronger communities and to address health disparities and the social determinants of health.[6] For example, Treasury cites investments in parks, public plazas, and other public outdoor recreation spaces that may respond to the needs of disproportionately impacted communities by promoting healthier living environments and outdoor recreation and socialization to mitigate the spread of COVID-19.[7]

Moreover, many governments saw significantly increased use of parks during the pandemic that resulted in damage or increased maintenance needs and associated costs. As such, Treasury allows the use of CSLFRF funds to “address administrative needs of recipient governments that were caused or exacerbated by the pandemic.”[8] These administrative needs include “increased repair or maintenance needs to respond to significantly greater use of public facilities.”[9]

While municipalities may be limited in the extent that CSLFRF can be used for public information efforts related to taxes and levies, a municipality can use CSLFRF to improve outdoor spaces or repair parks and public facilities, generally presumed eligible in disproportionately impacted communities, that may have experienced damage or increased maintenance needs due to the pandemic.[10]

Treasury may provide additional information when it issues new Frequently Asked Questions (“FAQs”) associated with the Final Rule.

Last revised: March 31, 2022

[1] Treas. Reg. 31 CFR 35 at 12, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Final-Rule.pdf.

[2] Id., at 423.

[3] Id., at 424.

[4] Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds: Overview of the Final Rule, at 11, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Final-Rule-Overview.pdf.

[5] Treas. Reg. 31 CFR 35 at 389, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Final-Rule.pdf.

[6] Id.

[7] Id., at 129.

[8] Id., at 189-190.

[9] Id.

[10] Id.

Program

COVID-19 Federal Assistance e311Topics

Vaccine DistributionFunding Source

American Rescue Plan Act, CARES Act, FEMAWhich resources are available for vaccine efforts, including but not limited to distribution, incentives, and community engagement? In addition, can you summarize resources available for vaccine efforts via the Federal Emergency Management Agency?

Municipalities have multiple avenues to obtain funding for vaccination efforts, including: (i) FEMA Public Assistance (“PA”) funding; (ii) grants provided through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (“CDC”); and (iii) the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Fund (“CSLFRF”) which is provided through the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (“ARP”). These resources apply to vaccine incentive programs and cover costs related to local vaccination efforts.

Municipalities should strongly consider using funding from more restrictive programs such as FEMA PA before tapping into sources that provide more flexibility, such as CSLFRF funding. FEMA PA is not capped or competitive, and thus offers an advantage to municipalities who use FEMA PA as the priority fund for any eligible activities not already funded by private insurance programs or the CDC.[1] Notably, as of November 2021, FEMA had already provided more than $6.1 billion for expenses related to COVID-19 vaccination at 100% federal cost share.[2] Note, the 100% federal cost share is in effect until July 1, 2022, and expenses incurred after this date will shift to 90% federal cost share until the end of the incident period.[3] FEMA funding may include costs for:

- Vaccination facilities, including community vaccination centers, mass vaccination sites, and mobile vaccinations, including necessary security and other services for sites.

- Medical and support staff, including contracted and temporary hires to administer vaccinations.

- Training and technical assistance for storing, handling, distributing, and administering of vaccinations.

- PPE, other equipment, supplies, and materials required for storing, handling, distributing/transporting, and administering vaccinations.

- Transportation support, such as refrigerated trucks and transport security, for vaccine distribution as well as reasonable transportation to and from the vaccination sites.

- Onsite infection control measures and emergency medical care for children and families at vaccination sites.

- Communication efforts that keep the public informed, including messaging campaigns, flyers, advertisements, websites, translation services, community engagement, and call centers or websites to assist with appointments or answering questions.[4]

If a municipality has exhausted its eligible expenditures under FEMA PA, it can then pursue other funding sources for expenditures ineligible for FEMA reimbursement.

The CDC is actively funding state, local, and territorial public health organizations responding to the COVID-19 pandemic, including vaccination efforts. The CDC has received supplemental funds through the Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act of 2020; the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act of 2020; the Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act; the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act of 2021; and most recently, the ARP.[5] The CDC is awarding funding received through these congressional appropriations to jurisdictions nationwide.[6] The ARP authorizes $130.2 billion in funds specifically allocated for local governments as a separate appropriation pursuant to CSLFRF.[7]

Municipalities may focus their efforts on coordinating with their respective state public health agencies, which predominantly serve as the pass-through entity for CDC funding. Working closely with the pertinent state public health agency may help to prevent depletion of the more flexible CSLFRF funding and will allow tapping into the direct state and federal funding for specific vaccination purposes.

The ARP separately authorizes an additional $7.5 billion as funding for COVID-19 vaccine activities at the CDC.[8] The ARP has designated funds to be available to the CDC specifically for such purposes as improving nationwide vaccine distribution and delivering technical support to local governments. As defined under this authority, “technical assistance” provides a host of vaccine efforts for municipalities, including:

- distribution and administration of vaccines;

- expansion of community vaccination centers;

- deployment of mobile vaccination areas;

- enhancement of data sharing and systems that increase vaccine efficiency, effectiveness, and uptake;

- facility enhancements;

- communications with the public; and

- transportation of individuals to facilitate vaccination.[9]

The U.S. Department of the Treasury’s (“Treasury”) Final Rule specifically includes vaccination programs as an eligible use of CSLFRF.[10]

Additionally, Treasury’s Final Rule expands the enumerated uses of CSLFRF funds to fund programs that provide incentives which are designed to: (i) influence people who would otherwise not get vaccinated; or (ii) assist people to get vaccinated more quickly, so long as the costs are reasonably proportional to the expected health benefit.[11] For example, Massachusetts provided fully vaccinated residents who are 18 or older a chance to win one of five $1 million prizes, while those between the ages of 12 and 17 were eligible to win one of five $300,000 scholarship grants in order to drive increases in vaccinations.[12] In New Jersey, the Governor’s Office launched the “Shot and a Beer” program to also encourage their eligible population to get vaccinated.[13] Municipalities may consider these expanded uses of CSLFRF funds when crafting their own programs.

Last Updated: March 25, 2022

[1] FEMA, Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act, P.L. 93-288 as Amended, Section 312, at 17-18, available at: https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/2020-03/stafford-act_2019.pdf.

[2] FEMA, “FEMA Funding for COVID-19 Response Continues,” available at: https://www.fema.gov/press-release/20211110/fema-funding-covid-19-response-continues. -

[3] FEMA, “FEMA Advisory: COVID-19 Cost Share,” at 1, available at: https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/documents/fema_covid-19-cost-share-extension_03012022.pdf

[4] FEMA, “FEMA Advisory: Federal Support to Combat COVID-19,” at 2–3, available at: https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/documents/fema_federal-support-combat-covid-19.pdf.

[5] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, COVID-19 State, Tribal, Local, and Territorial Funding, available at: https://data.cdc.gov/Administrative/COVID-19-State-Tribal-Local-and-Territorial-Fundin/tt3f-rr33

[6] CDC COVID-19 State, Tribal, Local, and Territorial Funding, available at: https://www.cdc.gov/budget/fact-sheets/covid-19/funding/index.html. See also “CDC Awards $3 Billion to Expand COVID-19 Vaccine Programs” available at: https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2021/p0407-covid-19-vaccine-programs.html.

[7] American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 § 9901, Pub. L. No. 117-2, amending 42 U.S.C. § 801 et seq., at Section 603(a), available at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/1319/text#HAECAA3A95C4E4FFAB6AA46CE5F9CB2B5.

[8] American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 § 2301, Pub. L. No. 117-2, amending 42 U.S.C. § 247d et seq., at Section 2301(a), available at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/1319/text#HAECAA3A95C4E4FFAB6AA46CE5F9CB2B5.

[9] Id., at Section 2301(b).

[10] Treas. Reg. 31 CFR 35 at 59, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Final-Rule.pdf.

[11] Id.

[12] National Governors Association, “Covid-19 Vaccine Incentives,” available at: https://www.nga.org/center/publications/covid-19-vaccine-incentives/.

[13] Id.

Program

COVID-19 Federal Assistance e311Topics

Housing & Rental Assistance, Program AdministrationFunding Source

American Rescue Plan ActWould purchasing vacant land or conveying vacant land to non-profit entities be eligible uses in an attempt to obtain affordable and attainable housing under the ARP?

Purchasing Vacant Land

Pursuant to guidance issued by the U.S. Department of the Treasury (“Treasury”) in the Final Rule, demolition and greening (or other structure or lot remediation) of vacant or abandoned properties, including residential, commercial, or industrial buildings, is an eligible use of the Coronavirus State Fiscal Recovery Fund and the Coronavirus Local Fiscal Recovery Fund (collectively, the “CSLFRF”). Further, costs associated with acquiring and securing legal title to vacant or abandoned properties and other related costs are permitted to “position the property for current or future productive use.”[1]

In response to public comment on the Interim Final Rule, Treasury underscored the need for safe, affordable housing and healthy neighborhood environments to restore public health and alleviate the pandemic’s negative economic effects, primarily on disproportionately impacted communities. “As such, certain services for vacant or abandoned properties are eligible.”[2] Eligible activities in addition to those listed above include:

- Rehabilitation, renovation, maintenance, or costs to secure vacant or abandoned properties to reduce negative impacts;

- Removal and remediation of environmental contaminants or hazards from vacant or abandoned properties, when conducted in compliance with applicable environmental laws or regulations;

- Demolition or deconstruction of vacant or abandoned buildings (including residential, commercial, or industrial buildings) paired with greening or other lot improvement as part of a strategy for neighborhood revitalization;

- Greening or cleanup of vacant lots, as well as other efforts to make vacant lots safer for the surrounding community;

- Conversion of vacant or abandoned properties to affordable housing; and

- Inspection fees and other administrative costs incurred to ensure compliance with applicable environmental laws and regulations for demolition, greening, or other remediation activities.[3]

As noted above, demolition and greening (or other structure or lot remediation) of vacant or abandoned properties, including residential, commercial, or industrial buildings, are eligible uses of funds. Treasury encourages recipients to undertake these activities to: (i) determine how the cleared property will be used to benefit the disproportionately impacted community; and (ii) integrate them as part of a neighborhood revitalization strategy. Activities under this eligible use should benefit current residents and businesses who experienced the pandemic’s impact on the community.[4]

Conveying Vacant Land to Nonprofit Entities

One of the four main eligible use categories of CSLFRF is “responding to the public health emergency or its negative economic impacts”[5] and the related subcategory, “assistance to nonprofits.”[6] Within the subcategory, Treasury specified the following eligible uses: “programs, services, or capital expenditures, including loans or grants to mitigate financial hardship such as declines in revenues or increased costs, or technical assistance.”[7] Treasury also expanded the definition of “nonprofit” in the Final Rule to include “501(c)(3) organizations and 501(c)(19) organizations.”[8]

To assist municipalities in determining the eligibility of nonprofit entities, Treasury streamlined its guidance regarding the identification of eligible populations: “the final rule maintains the ability for recipients to demonstrate a public health or negative economic impact on a class and to provide assistance to beneficiaries that fall within that class.”[9] Further, the Final Rule carries with it a presumption “that nonprofits operating in Qualified Census Tracts (‘QCTs’), operated by Tribal governments or on Tribal Lands, or operating in the U.S. territories were disproportionately impacted by the pandemic.”[10]

Under this guidance, CSLFRF recipients may determine that certain nonprofits were impacted or disproportionately impacted by the pandemic and provide responsive services.

Treasury also provided that nonprofits may receive funds from CSLFRF award recipients as both beneficiaries as well as subrecipients:

The final rule maintains the ability for the recipient to transfer, e.g., via grant or contract, funds to nonprofit entities to carry out an eligible use on behalf of the recipient… (e.g., developing affordable housing). When a recipient provides funds to an organization to carry out eligible uses of funds, the organization becomes a subrecipient. In this case, a nonprofit need not have experienced a negative economic impact in order to serve as a subrecipient.[11]

The guidance also instructs that nonprofits serving as subrecipients must comply with reporting requirements. Treasury states, “[a] nonprofit entity that receives a transfer from a recipient is a subrecipient. Per the Uniform Guidance, subrecipients must adhere to the same requirements as recipients.”[12]

Conclusion

While the Final Rule does not include language specifically regarding conveyance of land to nonprofit entities, it does include ways in which CSLFRF awards may be used to purchase vacant land to develop affordable housing. Award recipients should ensure compliance with the Final Rule, Treasury’s Reporting and Compliance Guidance,[13] and the Uniform Administrative Requirements, Cost Principles, and Audit Requirements for Federal Awards (“Uniform Guidance”)[14] when transferring funds to entities as subrecipients, including nonprofit entities.

Last Updated: January 31, 2022

[1] Treas. Reg. 31 CFR Part 35 at 134 -135, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Final-Rule.pdf.

[2] Id., at 134.

[3] Id.

[4] Id., at 135.

[5] Id., at 414.

[6] Id.

[7] Id., at 421.

[8] Id., at 160.

[9] Id., at 42.

[10] Id., at 146.

[11] Id., at 158 (emphasis added).

[12] Id., at 161.

[13] Department of Treasury, Compliance and Reporting Guidance: State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, (as of November 15, 2021), available at: SLFRF Compliance and Reporting Guidance Update 2.1 final (treasury.gov).

[14] 2 CFR Part 200, Uniform Guidance, available at: 2 CFR Part 200 - UNIFORM ADMINISTRATIVE REQUIREMENTS, COST PRINCIPLES, AND AUDIT REQUIREMENTS FOR FEDERAL AWARDS | CFR | US Law | LII / Legal Information Institute (cornell.edu).

Program

COVID-19 Federal Assistance e311Topics

Lost Revenue & Revenue ReplacementFunding Source

American Rescue Plan ActWhat is the proper course of action to take if a municipality identifies that it calculated lost revenue incorrectly? Can the funds be put back in the reserves?

Municipalities should follow the revenue calculation guidelines identified in the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (“ARP”) and further explained in both the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s (“Treasury”) Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (“CSLFRF”) Final Rule and Treasury’s CSLFRF Frequently Asked Questions (“FAQs”) as of January 2022.[1], [2], [3] If a municipality identifies lost revenue incorrectly and/or later identifies that its lost revenue was miscalculated or overcalculated, a municipality must reclassify the corresponding “re-identified” municipal funds into an appropriate municipal subaccount where the calculation error occurred.

Revenue Loss Re-Calculation

While municipalities should always apply their internal financial controls to ensure lost revenue is calculated correctly, Treasury provides municipalities with the opportunity to further identify revenue loss which was miscalculated or overcalculated, and to re-calculate that revenue loss. Treasury appears to recognize that the COVID-19 pandemic can affect economies at different points in time, stating in the Final Rule:

Recipients will have the opportunity to calculate revenue loss at several points throughout the program, recognizing that some recipients may experience revenue effects with a lag. This option to re-calculate revenue loss on an ongoing basis is intended to result in more support for recipients to avoid harmful cutbacks in future years.[4]

In addition, the FAQs state that “recipients should calculate the extent of the reduction in revenue as of four points in time: December 31, 2020; December 31, 2021; December 31, 2022; and December 31, 2023.”[5] In the Final Rule, Treasury has provided the choice to calculate revenue loss based on a fiscal year or a calendar year, provided that choice is maintained for the period of performance.[6] The Final Rule also adjusts for tax changes in order to give a more representative calculation of revenue loss due to the pandemic.[7]

Additionally, Treasury has provided the option for any recipient to use a standard allowance of $10 million for revenue loss. Any recipient can choose the standard allowance instead of calculating revenue loss but must maintain this choice for the entire period of performance.[8]

In the event of a miscalculation or overcalculation, municipalities should follow their internal budgetary procedures designated for reclassifying ineligible costs from the financial accounts identified for CSLFRF expenditures into or returning to the appropriate municipal fund subaccount(s). This reclassification explanation should be documented in accordance with internal financial control mechanisms, rules, procedures, and relevant Treasury and program rules. Notifying Treasury of the miscalculation should be included as a part of the initial interim report, or the quarterly or annual Project and Expenditure reports (which include subaward reporting, and in some cases annual Recovery Plan reports). The Final Rule does not address miscalculations, only re-calculating annually to capture a representative revenue loss over the period of performance. The Final Rule describes remediation and recoupment when Treasury identifies a potential violation in the use of funds but does not specifically address instances when a recipient self-identifies a miscalculation.[9] The municipality should maintain accounting records to assist with compiling and reporting accurate and compliant financial data in accordance with the appropriate accounting standards and principles.[10]

Use of Funds

The Final Rule gives municipalities broad latitude to use funds for the provision of government services.[11] Reviewing the FAQs and the Final Rule is recommended when determining eligible/ineligible uses.[12], [13]

As a reminder, Treasury’s CSLFRF Compliance and Reporting Guidance requires municipalities to take several steps to ensure that funds are used for permitted activities.[14] Municipalities are advised to carefully review the Uniform Administrative Requirements, Cost Principles, and Audit Requirements for Federal Awards (2 CFR Part 200) and any additional regulatory and statutory requirements applicable to the funding stream it is utilizing.[15]

It should be noted that additional information may be provided when Treasury issues new Frequently Asked Questions (“FAQs”) specific to the Final Rule.[16] In addition, Treasury encourages municipalities to consider the guidance issued in the Statement Regarding Compliance with the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds Interim Final Rule and Final Rule.[17]

Last Revised: March 11, 2022

[1] American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 § 9901, Pub. L. No. 117-2, amending 42 U.S.C. § 801 et seq., available at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/1319/text#HAECAA3A95C4E4FFAB6AA46CE5F9CB2B5.

[2] Treas. Reg. 31 CFR 35 at 236–238, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Final-Rule.pdf.

[3] Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds Frequently Asked Questions (as of January 2022) – FAQ #3.4 and #3.5, at 14, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRPFAQ.pdf.

[4] Treas. Reg. 31 CFR 35, at 391, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Final-Rule.pdf.

[5] Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds Frequently Asked Questions (as of January 2022) – FAQ #3.4, at 14, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRPFAQ.pdf.

[6] Treas. Reg. 31 CFR 35, at 249, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Final-Rule.pdf.

[7] Id., at 254-257.

[8] Id., at 240.

[9] Id., at 374-378.

[10] U.S. Department of the Treasury, Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, Compliance and Reporting Guidance (as of February 28, 2022), at 10, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Compliance-and-Reporting-Guidance.pdf.

[11] Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds Frequently Asked Questions (as of January 2022) – FAQ #3.8, at 15, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRPFAQ.pdf; see also id., at FAQ #2.1, at 4.

[12] Treas. Reg. 31 CFR 35, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Final-Rule.pdf.

[13] Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds Frequently Asked Questions (as of January 2022) – Section 8, at 34, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRPFAQ.pdf.

[14] U.S. Department of the Treasury, Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, Compliance and Reporting Guidance (as of February 28, 2022), available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Compliance-and-Reporting-Guidance.pdf.

[15] 2 CFR Part 200, available at: https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?tpl=/ecfrbrowse/Title02/2cfr200_main_02.tpl.

[16] Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, Frequently Asked Questions (as of January 2022), at 1, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRPFAQ.pdf.

[17] U.S. Department of the Treasury, Statement Regarding Compliance with the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds Interim Final Rule and Final Rule, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Compliance-Statement.pdf.

Program

COVID-19 Federal Assistance e311Topics

Due Diligence & Fraud ProtectionFunding Source

American Rescue Plan ActWhat documentation is a municipality required to supply in order to receive funds? What is the due date for the documentation?

Pursuant to its commitment to providing guidance and instructions on the reporting requirements,[1] on November 15, 2021, the United States Department of the Treasury (“Treasury”) published Version 2.1 of the Compliance and Reporting Guidance (“Reporting Guidance”) for CSLFRF.[2] The Reporting Guidance clarifies the compliance responsibilities of CSLFRF recipients and lists three reports that recipients may need to provide by specified deadlines, namely:

- Interim Report: “Provides an initial overview of status and uses of funding. This is a one-time report.”

- Project and Expenditure Report: “Report on projects funded, expenditures, and contracts and subawards over $50,000, among other information.”

- Recovery Plan Performance Report: “The Recovery Plan Performance Report (“Recovery Plan”) will provide information on the projects that large recipients are undertaking with program funding and how they plan to ensure program outcomes are achieved in an effective, efficient, and equitable manner. It will include key performance indicators identified by the recipient and some mandatory indicators identified by Treasury. The Recovery Plan will be posted on the website of the recipient as well as provided to Treasury.”[3]

Recipients will submit required reports via the Treasury Reporting CSLFRF portal.[4] On August 9, 2021, Treasury published updated guidance on submitting reports via the Portal, including the policy and technical requirements for entering information.[5]

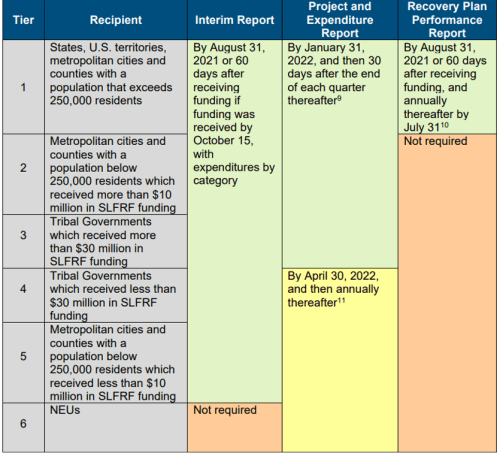

Treasury’s Reporting Guidance currently includes a graphic, including due dates, describing reporting requirements for three reports, delineated by CSLFRF recipient type as follows:[6]

The Reporting Guidance sets a deadline of August 31, 2021, for recipients to provide the one-time Interim Report on CSLFRF expenditures and obligations; this deadline applies to states, U.S. territories, metropolitan cities, counties, and Tribal governments (recipients other than Non-Entitlement Units of Local Government (“NEUs”)).[7] If funding was received after October 15, 2021, the Interim Report may be submitted 60 days after receiving funds. The Interim Report must reflect a recipient’s expenditures and obligations from the date of award to July 31, 2021, broken down by Expenditure Category (which can be selected from a menu of available options on the CSLFRF portal).[8] For purposes of reporting in the CSLFRF portal, an “expenditure” is an amount incurred as a liability of the entity (e.g., the service has been rendered or the good has been delivered to the entity),[9] and an “obligation” encompasses orders placed for property and services, contracts and subawards made, and similar transactions that require payment.[10] Appendix 1 of the Reporting Guidance contains the Expenditure Categories list.[11]

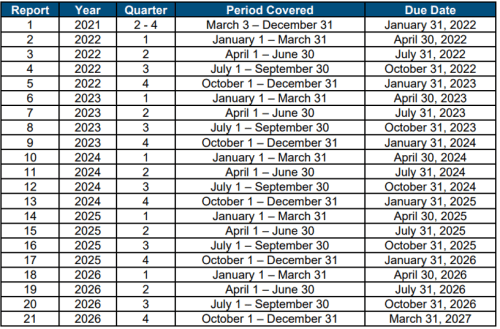

Treasury also establishes a requirement for Project and Expenditure Reports. The information required for these reports includes information regarding Projects, Expenditures, Project Status, Project Demographic Distribution, Subawards, Civil Rights Compliance, Programmatic Data, and NEU Distributions.[12] Additional information requirements are found on pages 14 to 22 of the Reporting Guidance. For all Tribal Governments that received over $30 million, as well as states, U.S. territories, and metropolitan cities and counties that either (1) have a population that exceeds 250,000 residents or (2) have fewer than 250,000 residents but received more than $10 million in CSLFRF funding, the first report is due January 31, 2022, and subsequent reports are to be filed quarterly as follows:[13]

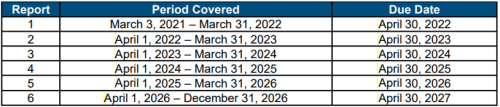

For NEUs, Tribal Governments that received less than $30 million in CSLR, and metropolitan cities and counties with populations lower than 250,000 residents and that receive less than $10 million in CSLFRF, the second Project and Expenditure Report is due April 30, 2022, and subsequent reports are due annually thereafter,[14] as follows:

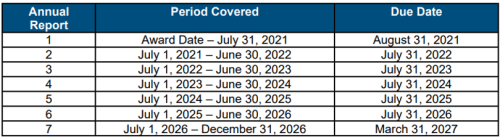

Treasury also requires states, U.S. territories, metropolitan cities, and counties with more than 250,000 residents to submit Recovery Plan Performance Reports and to post copies to the entity’s website by August 31, 2021, and annually thereafter. This report will provide the public and Treasury with information on the recipient’s planned and ongoing projects funded by its CSLFRF allocation and describe the recipient’s plans to achieve program outcomes effectively, efficiently, and equitably.[15] The first report will cover the period ending July 31, 2021. Treasury sets the following timeline for the submission of Recovery Plan Performance Reports:[16]

On November 5, 2021, Treasury released the most comprehensive revisions to the Compliance and Reporting Guidance for the SLFRF Program to date. The guidance provides additional detail and clarification for each recipient’s compliance and reporting responsibilities and should be read in concert with the Award Terms and Conditions, the authorizing statute, the Rule, and other regulatory and statutory requirements.

The Treasury is now accepting the Interim Report and the Recovery Plan Performance Report through Treasury’s Portal. Recipients should refer to Treasury’s Portal for Recipient Reporting, which includes step-by-step guidance for submitting the required SLFRF reports using Treasury’s Portal.

The Treasury also indicated that a forthcoming User Guide will provide information on submitting Project and Expenditure Reports. Additional resources located on its respective Recipient Compliance and Reporting Responsibilities page include the following:

- The Recovery Plan Template for States, territories, and metropolitan cities and counties with more than 250,000 residents;

- The Draft Non-entitlement Units of Government (NEU) Template; and

- The NEU Distribution Template User Guide.

It is important to note that the NEU Template is not the final version and should not be used for submission.[17] Recipients should use the template that will be posted in the Treasury Submission Portal once it opens to report information.[18]

Municipalities should conduct an in-depth review of the Reporting Guidance, as it provides additional detail regarding the information required to be included in each of these reports and is revised to reflect further reporting requirements as they become available.

Last Revised: November 19, 2021

[1] Previously, the Supplementary Information section preceding the Rule discusses Reporting requirements at a general level, noting, “Treasury will provide additional guidance and instructions on the reporting requirements…at a later date.” Treas. Reg. 31 CFR 35 at 112, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/FRF-Interim-Final-Rule.pdf.

[2] Department of Treasury, Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds—Compliance and Reporting Guidance, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Compliance-and-Reporting-Guidance.pdf.

[3] Id., at 12.

[4] Id., at 13 (see footnotes).

[5] Department of the Treasury, Treasury’s Portal for Recipient Reporting: State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, available at https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF_Treasury-Portal-Recipient-Reporting-User-Guide.pdf.

[6] Department of Treasury, Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds—Compliance and Reporting Guidance at 13, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Compliance-and-Reporting-Guidance.pdf.

[7] Department of the Treasury, Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds—Compliance and Reporting Guidance, at 13, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Compliance-and-Reporting-Guidance.pdf.

[8] Department of the Treasury, Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds—Compliance and Reporting Guidance, at 13-14, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Compliance-and-Reporting-Guidance.pdf.

[9] Id., (see footnotes).

[10] Id.

[11] Department of the Treasury, Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds—Compliance and Reporting Guidance, at 30-31, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Compliance-and-Reporting-Guidance.pdf.

[12] Id., at 16-23.

[13] Id., at 15-16.

[14] Id., at 16.

[15] Id., at 23-30.

[16] Id., at 23.

[17] Department of the Treasury, Draft Non-entitlement Units of Government (NEU) Template, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/NEU-Distribution-Templates.xlsx.

[18] Id.

Program

COVID-19 Federal Assistance e311Topics

Lost Revenue & Revenue ReplacementFunding Source

American Rescue Plan ActShould federal, state, and local grants be included when calculating revenue loss for the ARP?

For calculating lost revenue pursuant to the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (“ARP”) and the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (“CSLFRF”), intergovernmental transfers from the federal government should be excluded from general revenue calculations. However, intergovernmental transfers from state and local governments can generally be included unless it is a pass-through transfer of funding from the federal government.

The U.S. Department of the Treasury (“Treasury”) Final Rule’s definition of general revenue excludes “intergovernmental transfers from the Federal Government, including transfers made pursuant to section 9901 of the American Rescue Plan Act.”[1] In particular, Treasury’s Compliance and Reporting Guidance states:

In calculating general revenue, recipients should have excluded all intergovernmental transfers from the federal government. This includes, but is not limited to, federal transfers made via a State to a locality pursuant to the CRF or [CSLFRF]. To the extent federal funds are passed through States or other entities or intermingled with other funds, recipients should have attempted to identify and exclude the federal portion of those funds from the calculation of general revenue on a best-efforts basis.[2]

However, intergovernmental transfers other than from the federal government are included in the definition of “general revenue.”[3] Intergovernmental transfers are defined as “money received from other governments, including grants and shared taxes.”[4]

Therefore, for the purpose of calculating revenue loss, municipalities should exclude funds transferred from the federal government and should include intergovernmental transfers between state and local governments.

Last Updated: March 31, 2022

[1] Treas. Reg. 31 CFR 35 at 408, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Final-Rule.pdf.

[2] Department of Treasury, Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds: “Guidance on Recipient Compliance and Reporting Responsibilities,” at 17, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Compliance-and-Reporting-Guidance.pdf.

[3] Treas. Reg. 31 CFR 35 at 246, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Final-Rule.pdf.

[4] Id., at 246.

Program

COVID-19 Federal Assistance e311Topics

Lost Revenue & Revenue ReplacementFunding Source

American Rescue Plan ActWhen excluding certain revenues for revenue loss calculations, must a municipality also exclude those same revenues from its base year?

Yes. When excluding certain revenues for the revenue loss calculation under the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021’s (“ARP”) Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (“CSLFRF”), a municipality must exclude those same revenues from the base year.

The U.S. Department of the Treasury’s (“Treasury”) CSLFRF Final Rule adopts the definition of “General Revenue”[1] which was based largely on the concept of “General Revenue from Own Sources.”[2] This is the case as explained in the Census Bureau’s Government Finance and Employment Classification manual, with limited exceptions including the treatment of certain intergovernmental transfers and liquor store revenues.[3] This definition ensures consistency when assessing which revenues to include and exclude in calculating revenue loss both in the base year and in future years. In a recent update to its CSLFRF Frequently Asked Questions (“FAQs”) for the Final Rule, Treasury included an Appendix that municipalities can review to assist in their determination of which of their respective revenue streams may qualify as General Revenue.[4]

The Final Rule establishes the following process for calculating revenue:

Recipients should calculate the extent of the reduction in revenue as of four points in time: December 31, 2020; December 31, 2021; December 31, 2022; and December 31, 2023. To calculate the extent of the reduction in revenue at each of these dates, recipients should follow a four-step process:

Step 1: Identify revenues collected in the most recent full fiscal year prior to the public health emergency (i.e., last full fiscal year before January 27, 2020), called the base year revenue.

Step 2: Estimate counterfactual revenue, which is the amount of revenue the recipient would have expected in the absence of the downturn caused by the pandemic. The counterfactual revenue is equal to base year revenue * [(1 + growth adjustment) ^ ( n/12)], where n is the number of months elapsed since the end of the base year to the calculation date, and growth adjustment is the greater of the average annual growth rate across all State and Local Government “General Revenue from Own Sources” in the most recent three years prior to the emergency, 5.2 percent, or the recipient’s average annual revenue growth in the three full fiscal years prior to the COVID-19 public health. emergency. This approach to the growth rate provides recipients with the option to use a standardized growth adjustment when calculating the counterfactual revenue trend and thus minimizes administrative burden, while not disadvantaging recipients with revenue growth that exceeded the national average prior to the COVID-19 public health emergency by permitting these recipients to use their own revenue growth rate over the preceding three years.

Step 3: Identify actual revenue, which equals revenues collected over the past twelve months as of the calculation date.

Step 4: The extent of the reduction in revenue is equal to counterfactual revenue less actual revenue. If actual revenue exceeds counterfactual revenue, the extent of the reduction in revenue is set to zero for that calculation date.[5]

Treasury may provide additional information when it issues new FAQs associated with the Final Rule.

Last Updated: March 31, 2022

[1] Treas. Reg. 31 CFR 35 at 408, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Final-Rule.pdf.

[2] Id., at 243.

[3] U.S. Bureau of the Census, Government Finance and Employment Classification Manual, October 2006, at 3-4, available at: https://www2.census.gov/govs/pubs/classification/2006_classification_manual.pdf.

[4] Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, Frequently Asked Questions (as of January 2022), at 43, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRPFAQ.pdf.

[5] Treas. Reg. 31 CFR 35 at 236-237, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Final-Rule.pdf.

Program

COVID-19 Federal Assistance e311Topics

Program AdministrationFunding Source

American Rescue Plan ActWould an incentive program for residents to connect to existing sewer lines be considered an eligible use of ARP funding?

The U.S. Department of the Treasury’s (“Treasury”) Final Rule regarding the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (“CSLFRF”) of the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (“ARP”) does not expressly indicate whether municipalities using ARP funds for the purpose of establishing or operating an incentive program to connect residents to existing sewer lines would be an eligible use of funds. However, the Final Rule states:

eligibilities include the development and implementation of incentive and educational programs that address and promote water conservation, source water protection, and efficiency related to infrastructure improvements, e.g., incentives such as rebates to install green infrastructure such as rain barrels or promote other water conservation activities.[1]

Treasury’s CSLFRF Frequently Asked Questions (“FAQs”) state that municipalities have some leeway in determining whether a water, sewer, or broadband project is eligible:

Recipients do not need approval from Treasury to determine whether an investment in a water, sewer, or broadband project is eligible under [CSLFRF]. Each recipient should review [applicable Treasury guidance] in order to make its own assessment of whether its intended project meets the eligibility criteria … A recipient that makes its own determination that a project meets the eligibility criteria as outlined in [Treasury guidance] may pursue the project as a [CSLFRF] project without pre-approval from Treasury. Local government recipients similarly do not need state approval to determine that a project is eligible under [CSLFRF]. However, recipients should be cognizant of other federal or state laws or regulations that may apply to construction projects independent of CSFRF/CLFRF funding conditions and that may require pre-approval.[2]

For water and sewer projects, [Treasury guidance] refers to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Drinking Water and Clean Water State Revolving Funds (SRFs) for the categories of projects and activities that are eligible for funding. Recipients should look at the relevant federal statutes, regulations, and guidance issued by the EPA to determine whether a water or sewer project is eligible. Of note, [Treasury guidance] does not incorporate any other requirements contained in the federal statutes governing the [CSLFRF] or any conditions or requirements that individual states may place on their use of [CSLFRF].[3]

Under guidance given by the Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA”) for State Revolving Funds (“SRFs”) (which Treasury has stated should guide CSLFRF recipients):

States may customize loan terms to meet the needs of small and disadvantaged communities, or to provide incentives for certain types of projects. Beginning in 2009, Congress authorized the CWSRFs to provide further financial assistance through additional subsidization, such as grants, principal forgiveness, and negative interest rate loans. Through the Green Project Reserve, the CWSRFs target critical green infrastructure, water and energy efficiency improvements, and other environmentally innovative activities.[4]

If the municipality determines that an incentive program meets the intended eligibility criteria to fulfill a sewer infrastructure project and can be appropriately documented, the incentive program could satisfy eligibility requirements for CSLFRF funding.

Treasury may provide additional information when it issues new FAQs specific to the Final Rule.[5]

Last Updated: March 31, 2022

[1] Treas. Reg. 31 CFR 35, at 293, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Final-Rule.pdf.

[2] Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, Frequently Asked Questions (as of January 2022) – FAQ #6.7, at 29, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRPFAQ.pdf.

[3] Id. (emphasis added).

[4] Environmental Protection Agency, Learn about the Clean Water State Revolving Fund (CWSRF) (emphasis added), available at: https://www.epa.gov/cwsrf/learn-about-clean-water-state-revolving-fund-cwsrf#eligibilities.

[5] Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, Frequently Asked Questions (as of January 6, 2022), at 1, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRPFAQ.pdf.

Program

COVID-19 Federal Assistance e311Topics

Program AdministrationFunding Source

American Rescue Plan ActMay municipalities use ARP funds to supplement salaries for municipal employees whose salaries were reduced in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic?

The American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (“ARP”) Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (“CSLFRF”) Final Rule, issued by the U.S. Department of the Treasury (“Treasury”) on January 6, 2022, clarifies how municipalities can address the issue of municipal employees who faced salary reductions due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the circumstances in which those employees may receive supplemental salaries.

Municipalities that furloughed employees or reduced employee pay are eligible for funding under the Final Rule. Specifically, the pay reduction or furlough must have been primarily and substantially due to the public health emergency or its negative economic impacts, and recipients must provide supporting documentation to that effect.[1] The Final Rule also indicates that unemployment insurance benefits received by the furloughed employee during the furlough period must be taken into account in order to meet the requirement that the additional funding is reasonably proportional to the negative economic impact of the pay cut or furlough of the employee.[2]

The Final Rule maintains the provisions related to premium pay for workers who performed essential services during the COVID-19 public health emergency.[3] The ARP as well as Treasury’s Final Rule authorize recipients to use CSLFRF to provide premium pay to eligible workers performing duties during the COVID-19 public health emergency that are considered “essential,” subject to certain factors and limitations detailed below.[4] Workers who do not perform work that meets the criteria to be considered essential work would not be eligible for premium pay.[5]

The Final Rule defines “premium pay” as an additional amount of up to $13 per hour paid to an eligible worker for work performed during the COVID-19 pandemic and capped at $25,000 for any single eligible worker (per period of performance for the CSLFRF program, though recipients should periodically reassess their determination of primarily dedicated staff, including as the public health emergency and response evolves).[6] The ARP defines eligible workers as those “needed to maintain continuity of operations of essential critical infrastructure sectors and additional sectors” designated as “critical to protect[ing] the health and well-being of the residents [by] each chief executive officer of a metropolitan city, non-entitlement unit of local government, or county.”[7] The Final Rule identifies 24 categories of “critical” infrastructure sectors, including health care and emergency response. While all such public employees are “eligible workers” and the chief executive (or equivalent) may designate additional non-public sectors as critical, in order to receive premium pay, these workers must still meet the other premium pay requirements (e.g., performing essential work).[8] For purposes of determining who may receive premium pay, guidance from Treasury defines “essential work” as involving regular in-person interactions with patients, the public, or coworkers, or regular physical handling of items also handled by patients, the public, or coworkers.[9] Essential work does not include any work performed while teleworking from a residence.[10]

Treasury encourages recipients to consider providing premium pay retroactively for work performed during the pandemic, but notes that “funds may not be used to reimburse a recipient or eligible employer grantee for premium pay or hazard pay already received by the employee.”[11] Additionally, the Final Rule states that premium pay programs should “prioritize[s] low- and moderate-income persons, given the significant share of essential workers that are low- and moderate-income.”[12] Treasury’s guidance sets limits that appear to further that priority, noting that premium pay that would increase a worker’s total pay above 150 percent of the state or county average annual wage (whichever is greater) requires “written justification to Treasury detailing how the award responds to eligible workers performing essential work.”[13]

Notably, Treasury has stated that recipients should maintain records to support their assessments of premium pay eligibility, such as “payroll records, attestations from supervisors or staff, or regular work product or correspondence demonstrating work on the COVID-19 response.”[14] Treasury also advises recipients to periodically reassess their determinations. Treasury clarified its position on documenting justification on how premium pay responds to eligible workers performing essential work, noting in the Final Rule that written justification means:

a brief, written narrative justification of how the premium pay or grant is responsive to workers performing essential work during the public health emergency. This could include a description of the essential workers’ duties, health or financial risks faced due to COVID-19, and why the recipient determined that the premium pay was responsive despite the workers’ higher income.[15]

Municipalities may consider tracking premium pay for employees separate from employees’ regular payroll through a separate billing code or account to ensure proper recordkeeping. A failure to maintain accurate records could lead to a clawback after the funds are received.

In addition to the explicit authorization of premium payments to eligible workers, the ARP authorizes certain assistance to individuals impacted by COVID-19. This can include direct financial and programmatic assistance to individuals experiencing economic harm (such as loss of employment or reduction in compensation) as a result of the pandemic.[16] This is applicable in the following areas:

- Assistance to unemployed and underemployed workers, “including job training, for individuals who want and are available for work, including those who have looked for work sometime in the past 12 months or who are employed part time but who want and are available for full-time work”[17]; and

- Assistance to households, including cash assistance or job training to address negative economic or public health impacts experienced.[18]

Additional information may be provided when Treasury issues new Frequently Asked Questions (“FAQs”) specific to the Final Rule, as indicated in the Interim Final Rule FAQ updated simultaneously with the issuance of the Final Rule.[19] In addition, Treasury encourages municipalities to consider the guidance issued in the Statement Regarding Compliance with the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds Interim Final Rule and Final Rule.[20]

Last Updated: February 4, 2022

[1] Treas. Reg. 35 CFR 31 at 183, available at https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Final-Rule.pdf.

[2] Id.

[3] Id., at 219-233.

[4] Id., at 231.

[5] Id., at 226-227.

[6] Id., at 178 and 230-232.

[7] American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 § 9901, Pub. L. No. 117-2, amending 42 U.S.C. § 801 et seq., at Section 603(g)(2), available at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/1319/text#HAECAA3A95C4E4FFAB6AA46CE5F9CB2B5.

[8] Treas. Reg. 31 CFR 35 at 224, available at https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Final-Rule.pdf.

[9] Id., at 407-408.

[10] Id., at 225-226.

[11] Id., at 232-233.

[12] Id., at 227-230.

[13] Id.

[14] Id., at 175.

[15] Id., at 230.

[16] Id., at 116.

[17] Id.

[18] Id., at 80.

[19] Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, Interim Final Rule Frequently Asked Questions, FAQ Introduction (as of January 6, 2022), available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRPFAQ.pdf.

[20] U.S. Department of the Treasury, Statement Regarding Compliance with the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds Interim Final Rule and Final Rule, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Compliance-Statement.pdf.

Program

COVID-19 Federal Assistance e311Topics

Lost Revenue & Revenue ReplacementFunding Source

American Rescue Plan ActWhere a municipality’s sales tax rate was reduced in the base year for revenue calculation (leading to understated revenue loss), could an adjustment be made to compensate for the change in sales tax?

The U.S. Department of the Treasury’s (“Treasury”) Final Rule requires municipalities to accommodate for changes in tax policy adopted on or after January 6, 2022:[1]

Treasury is providing in the final rule that changes in general revenue that are caused by tax cuts adopted after the date of adoption of the final rule (January 6, 2022) will not be treated as due to the public health emergency, and the estimated fiscal impact of such tax cuts must be added to the calculation of “actual revenue” for purposes of calculation dates that occur on or after April 1, 2022.[2]

Treasury does not specifically address retroactively calculating the impact of past tax policy changes on revenue loss, specifically those enacted before January 6, 2022, or for calculation dates before April 1, 2022. However, Treasury anticipates updating its Frequently Asked Questions (“FAQs”) to address relevant questions arising from the Final Rule.[3]

As it stands, municipalities should not retroactively adjust base year revenue to remove the impact of tax policy changes enacted before January 6, 2022. Municipalities should follow the guidelines listed in the Final Rule, which do not include adjusting for tax policy changes in base year revenue. Municipalities should remain on the lookout for updated FAQs from Treasury regarding guidance issued in the Final Rule. In the meantime, municipalities can ask Treasury to address questions such as this one by emailing SLFRP [at] treasury.gov (SLFRP[at]treasury[dot]gov).

To provide greater flexibility in the use of Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (“CSLFRF”), the Final Rule provides recipients with a second way to access revenue replacement funds, creating:

an option for recipients to use a standard allowance for revenue loss. Specifically, in the final rule, recipients will be permitted to elect a fixed amount of loss that can then be used to fund government services. This fixed amount, referred to as the "standard allowance," is set at $10 million total for the entire period of performance. Although Treasury anticipates that this standard allowance will be most helpful to smaller local governments and Tribal governments, any recipient can use this standard allowance instead of calculating revenue loss pursuant to the formula above, so long as recipients employ a consistent methodology across the period of performance (i.e., choose either the standard allowance or the regular formula). Treasury intends to amend its reporting forms to provide a mechanism for recipients to make a one-time, irrevocable election to utilize either the revenue loss formula or the standard allowance.[4]

It is crucial to note that Treasury also states that recipients “must choose one of the two options and cannot switch between these approaches after an election is made.”[5] Treasury has also clarified that the standard allowance is up to $10 million, and it cannot exceed a municipality’s total CLSFRF award amount.[6]

Last Updated: February 16, 2022

[1] Treas. Reg. 31 CFR Part 35 at 252, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Final-Rule.pdf.

[2] Id., at 254.

[3] Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, Frequently Asked Questions (as of January 2022), at 1, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRPFAQ.pdf.

[4] Treas. Reg. 31 CFR Part 35 at 240, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Final-Rule.pdf.

[5] Department of Treasury, Coronavirus State & Local Fiscal Recovery Funds: Overview of the Final Rule, (as of January, 2022), at 9, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Final-Rule-Overview.pdf.

Program

COVID-19 Federal Assistance e311Topics

Timing of FundsFunding Source

American Rescue Plan ActIs the receipt of the second tranche of ARP funding contingent on the municipality spending the entire first tranche?

Based on current guidance, local governments that qualify as “metropolitan cities” are not obligated to spend the first tranche as a condition precedent for receiving the second tranche of funding through the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021’s (“ARP”) Coronavirus Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (“CLFRF”). Specifically, section 603(b)(7) of the ARP provides that the United States Department of the Treasury (“Treasury”) will make payments to local governments in two tranches, with the second tranche being paid twelve months after the first payment.[1]

The text of the ARP indicates that the measure of state unemployment[2] and limitations to Non-Entitlement Units of Local Government (“NEU”)[3] are the only limitations to receiving the second tranche of CLFRF funds. Having said that, Treasury has indicated that guidance regarding the second tranche of funding will be released closer to May 2022. In the specific case of NEUs, the municipality will not be eligible to receive more than 75 percent of its respective operating budget.[4] Allocations to NEUs will be made through their state governments.

Last Updated: July 19, 2021

[1]American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 § 9901, Pub. L. No. 117-2, amending 42 U.S.C. § 801 et seq., https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/1319/text#HAECAA3A95C4E4FFAB6AA46CE5F9CB2B5.

[2] U.S. Department of the Treasury, Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Fund, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/policy-issues/coronavirus/assistance-for-state-local-and-tribal-governments/state-and-local-fiscal-recovery-funds.

[3] U.S. Department of the Treasury, Coronavirus Local Fiscal Recovery Fund: Guidance On Distribution of Funds to Non-Entitlement Units of Local Government, available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/NEU_Guidance.pdf.

[4] Id., at 5.