What yesterday’s leaders can teach us about today’s crisis

No pressure, but how mayors handle the Covid-19 crisis is likely to define their legacy as leaders for years to come.

That weighty reminder was just one message Harvard Business School Professor Nancy Koehn presented during the latest online coaching and learning session of the Covid-19 Local Response Initiative. The good news, said Koehn, a historian who studies crisis leadership, is that even in the most difficult and calamitous situations, “a lot of leaders get better in these moments.”

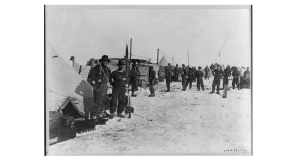

To illustrate her point, Koehn told city leaders the story of British explorer Ernest Shackleton, whose crew of 27 were shipwrecked and stranded for more than a year and a half during a 1914–16 expedition to Antarctica.

Years after every man returned home safely, journalists asked crew members how an impossible return to safety had been made possible. All had the same answer, Koehn said: “The boss [the crew’s nickname for Shackleton] made us believe we could do it.”

While Shackleton’s crisis is decidedly different than what mayors face today, Koehn said there are key lessons city leaders can take from it.

1. Stick to the mission and be flexible about the tasks. Once Shackleton’s expedition turned into a crisis, he defined his new mission clearly — bring all his men home safely — and communicated clearly with them about what daily routines and tasks were needed to achieve that goal. While that mission could never budge, he remained flexible and improvisational about how he and his team worked to achieve this, as everything from the weather to morale shifted from day to day.

That’s something mayors today can identify with, as they wrestle with uncertainty and a constantly changing set of circumstances, from rising Covid-19 caseloads to a collapsing economy. “All great crisis leaders are absolutely stubborn about the mission: We are going to navigate through Covid-19 and the economic fallout,” Koehn said. Yet there’s “this great suppleness and flexibility about how we do it as the situation changes.”

[Get the City Hall Coronavirus Daily Update. Subscribe here.]

2. Take responsibility and risks. Shackleton not only took responsibility for the situation but also for keeping up the morale of his team. Koehn said he believed his biggest enemy was not starvation or the cold, as important as these elements were, but doubt — and the possibility that his men would stop following him. If he sensed one crew member was having a rough time, he would order a round of hot milk for all of them, thus reviving their bodies and spirits without singling out the man who was struggling. Those he sensed were skeptical of his plans he invited to stay with him in his own tent.

At the same time, Shackleton took great risks, like setting off on an 800-mile voyage in a 23-foot lifeboat, knowing that he would need to learn his way through uncertain situations. That’s especially relevant today, Koehn said.

“We’ve got to get comfortable with a lot of uncertainty and chaos, too little information and changing information, and then with navigating from point to point,” Koehn continued. “We’re going to pivot when we make mistakes and learn quickly from that pivot and then navigate to the next point on the horizon. I don’t know any great crisis leader and his or her people who have ever come through a crisis any differently.”

3. Acknowledge feelings and manage energy. Shackleton knew that creating routines was important to creating stability for his team and thus sustaining their spirits. For the seven months that the men lived in tents on the ice, they followed weekly and daily routines. For example, the Union Jack went up at sunrise and down at sunset. Everyone had duties assigned and was required to exercise every day. Each night after dinner, Shackleton would meet with the crew to give them the latest updates. Keeping up routines matters today, as well, both for city staff and residents.

“Frequent, predictable communication is absolutely essential,” Koehn said. “Reduce the uncertainty enough for [people] that they’re not without grounding. They’re not giving way to panic. The hoarding stops. All those aspects of your leadership, including regular communication, make a big, positive difference.”

How you show up matters, Koehn continued, pointing to a photo of Shackleton looking confident in a fedora, hands locked in his suspenders. “What’s your body language? What kind of demeanor and energy are you portraying? People are so hungry for guidance and confidence and seriousness of purpose right now that they are taking their cues from all kinds of nonverbal behaviors.”

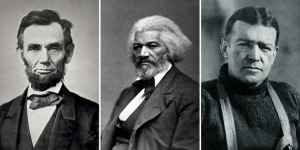

4. Secure your own mask before helping others. Leadership invites loneliness even during good times; during a crisis it’s physically exhausting and emotionally depleting. Koehn cautioned mayors, based on the experience of not just Shackleton but also Abraham Lincoln, Frederick Douglass, and Winston Churchill to carve out personal time to recover every day. “Find a way to feed and water yourself,” she said, “because this is not a sprint, it’s a marathon.”

What mayors are doing serving their communities, Koehn said, “is an extraordinary gift that you are offering” to a public that, history suggests, may not always show its gratitude. “Let me just say, as someone who makes a living studying leaders who make themselves better in a crisis: Thank you, thank you, thank you!”

(Lincoln and Shackleton photos courtesy of Library of Congress and Douglass photo courtesy of the National Archives.)