Reopening City Hall — safely

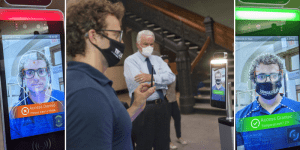

It’s the latest thing you wouldn’t have imagined back in January: A screen that takes your temperature and assesses whether you’re wearing a face mask.

And if you’re headed into City Hall or any other municipal building in Jersey City, N.J., you’ll have to look right at one and wait for the green light to enter.

The devices, which cost about $1,700 each and will be paid for with federal CARES Act funds, are just one of many layers of protection for city employees as they head back to work, said Brian Platt, the city’s business administrator.

Any visitors who have a body temperature above 100.4 degrees are turned away by a security guard and given information on where to get a free COVID-19 test. (Those who don’t have a mask can pick one up for free at the door.) Employees who have a fever are required to get a COVID-19 test immediately and quarantine for a few days, or longer if the test comes back positive.

“It’s a simple solution to a staffing problem,” Platt said. “When we first started to bring employees back to the office and to let visitors into our municipal facilities, we had a person designated at each facility to manually check face masks and manually check body temperatures. This technology allows us to automate that process and not have to take somebody off their regular daily responsibilities to do this job.”

Four months after just about every city hall in the country closed its doors to stop the spread of coronavirus, local governments have mixed approaches when it comes to bringing staff back in to work in the office. In Jersey City, where cases peaked in April but are minimal now, municipal offices fully opened for the first time on Monday. Municipal buildings also opened this week in Brockton, Mass., Muskegon, Mich., and South Portland, Me., among other places.

At the same time, surging COVID-19 cases in some parts of the country and tiny blips in others, are throwing a wrench in many city hall reopening plans. This week, Greenville, Tenn., La Crosse, Wis., and Midland, Texas, closed their municipal offices, citing growth in community spread of the virus. Meanwhile, Cambridge, Mass., Clovis, N.M., and Elkins, W.Va., locked down this week after someone working in each of those cities tested positive.

The stakes are big. Across the country, scores of municipal workers have died from COVID-19, including at least 260 in New York City alone. Transit workers, firefighters, and other essential workers have been at the greatest risk, but office employees are vulnerable, too. In the Atlanta suburb of Fairburn, Ga., where leaders resisted allowing employees to telework, a 57-year old police department clerk died of COVID-19 in April.

City leaders are taking a number of precautions to keep employees safe as they reopen city buildings. In addition to screening for fevers, symptoms, and face-mask wearing at the door, common precautions include:

- Phasing in the return of employees, prioritizing those whose jobs require face-to-face contact that can’t be done easily remotely.

- Implementing staggered and flexible schedules to reduce the density of employees in the building.

- Making hand sanitizer widely available, and targeting doors, counters, and other high-touch surfaces for enhanced cleaning.

- Installing plexiglass barriers in customer service areas.

- Requiring residents to make appointments to take care of city business in order to reduce crowding in hallways or waiting areas.

- Creating special visiting hours for residents over the age of 65 or with underlying medical conditions.

- Closing restrooms to public use or allowing only one person in at a time.

- Creating one-way paths through the building and limiting the number of people riding elevators together.

- Encouraging social distancing with signage and floor stickers marking six-foot intervals.

- Encouraging residents to conduct business online or over the phone, when possible.

Jersey City is doing many of these things and more, in what Mayor Steven Fulop has called “the new normal.” The city has brought employees back in phases, starting with 25 percent of staff in May and ramping up from there. They’ve implemented staggered shifts, so that instead of everyone working from 9-to-5, some work from 6 am to 2 pm, and others from 2 pm to 10 pm. The city will soon start offering a four-day workweek of ten hours a day — rather than five eight-hour days — on a voluntary basis.

Employees with underlying health conditions or in high-risk categories can still work from home, Platt said, and “we’re trying to be as accommodating as possible” for parents whose child care options have dried up. Employees working out of city offices are required to get tested for COVID-19 at least once a month. Workspaces have been moved to be at least six feet apart, and adjacent desks have partitions between them.

Then there’s the technology at the front door. While the new scanners are capable of performing facial recognition and storing those images, Platt said those features are turned off. “We’re not storing any personal data for anyone that comes in the building,” he said. “It’s not logging the body temperature of anyone. It’s just sort of a yes or no. Can you come in or not?”

It’s all part of what Platt described as the city’s “aggressive measures” to get COVID-19 under control. “I feel really hopeful and optimistic about our approach to limiting and stopping the spread of the virus,” Platt said. “We’re going to have some ups and downs over the next few weeks and months here, locally, and also across the country and around the world. And it’s up to us to be vigilant and to be strict with this. It’s going to be uncomfortable for a little while, but it’s a small price to pay to do what we can to stop the spread of the virus and ultimately save lives.”

More resources: