Mayors must think of reopening as akin to ‘turning on a faucet’ that can be closed again, health expert says

As President Trump on Sunday night extended federal guidance on social distancing through the end of April, the question of when it will be safe to reopen cities again rose to the top of mayors’ minds.

But according to Dr. Tom Frieden, one of the world’s leading health experts, city leaders should focus not on “when” but on “how.” Now that we are all working together toward a common goal, we should be asking ourselves, What does success look like? And, importantly, How do we get there?

Frieden, who served as New York City’s Health Commissioner under Mayor Michael Bloomberg and directed the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention under President Barack Obama, stressed to mayors participating in the Coronavirus Local Response Initiative that they shouldn’t be focused on simply choosing a date to end the stay-at-home orders currently in place across the country. In fact, he said, it wouldn’t be wise to simply reopen everything all at once.

[Get the City Hall Coronavirus Daily Update. Subscribe here.]

Rather, he said mayors should think of reopening as akin to turning on a faucet. “If we turn on the faucet gingerly, we can see if it’s exceeding our capacity to care for people who are very ill, to trace all contacts, and then to drive that cluster down,” Frieden said. “If we open the floodgates, it’s going to be a bigger disruption to our economy and our healthcare system.”

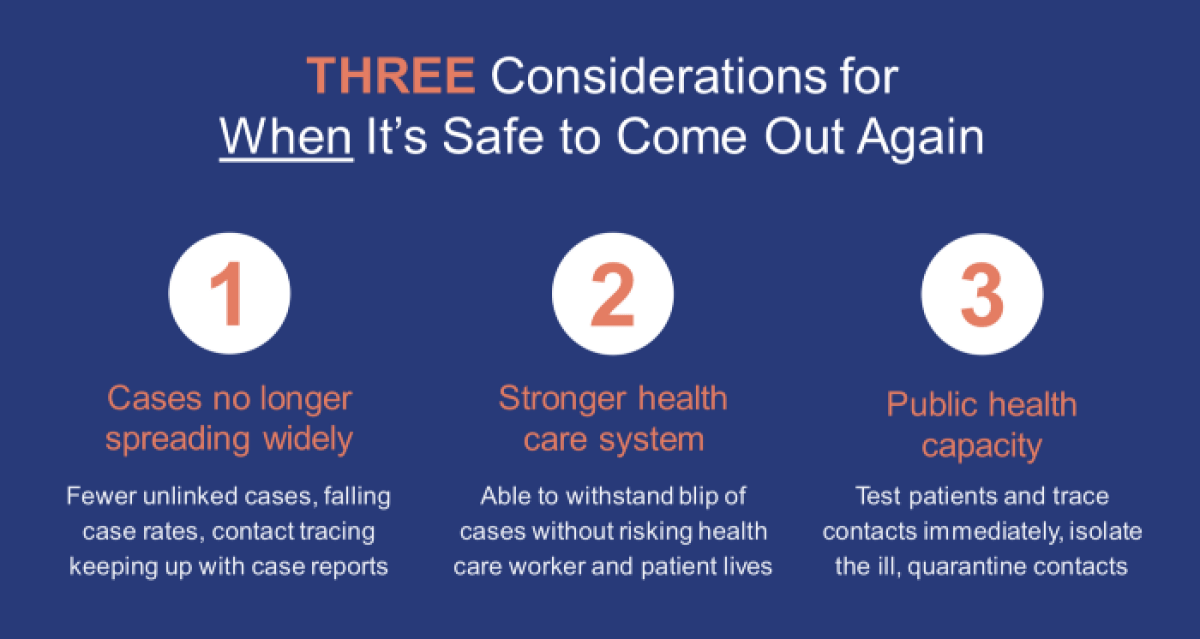

Frieden said that in order to open the faucet, mayors should first ensure three conditions are present:

- Cases are no longer spreading widely. Not only are the rate of new cases be falling, but there are fewer numbers of unlinked cases, where it’s unclear how people became infected.

- The local health care system is stronger. This is when it’s clear that it would take more than a blip of new cases to overwhelm area hospitals, their intensive care units, and their staffs.

- There’s capacity in the public-health departments. A good indication of this capacity is when the work these departments undertake to trace contacts of people exposed to the virus is able to keep up with reports of new cases. It’s also when there’s capacity to test patients, isolate those in recovery, and quarantine people they’ve been in contact with.

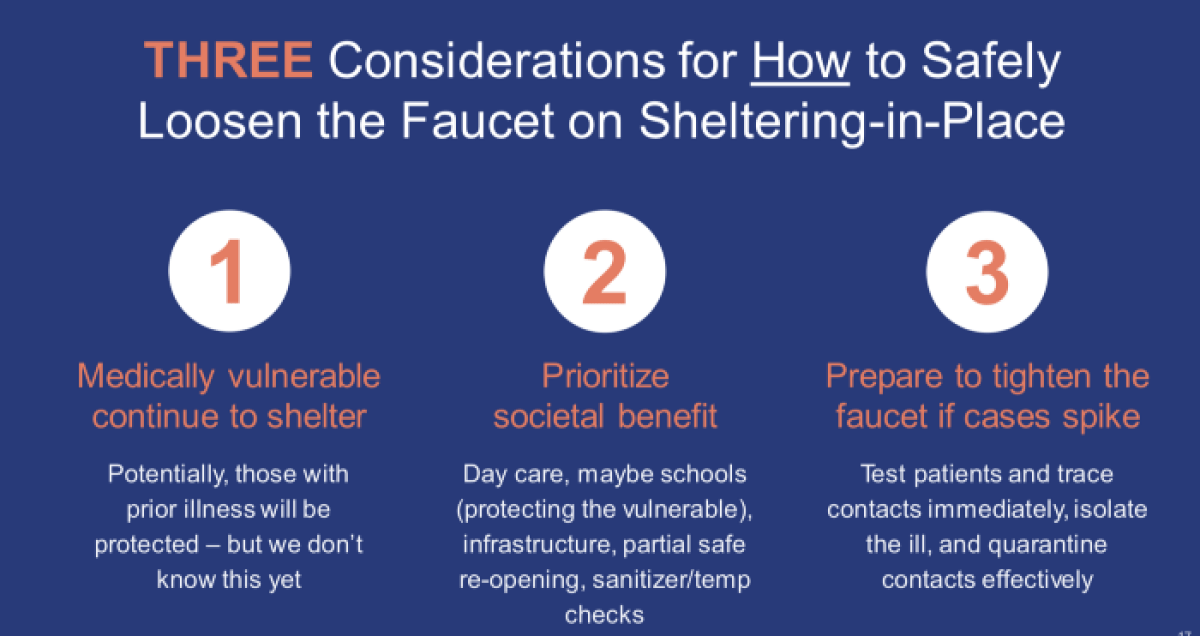

Once the decision to open the faucet is made, Frieden said, there are three considerations for how to do so safely:

- Medically vulnerable people will continue to need to stay home. When it comes to the elderly, cancer survivors, patients with heart disease, lung disease, and others at high risk, Frieden said, “you’re going to keep them sheltered from others, potentially for a long time.”

- Prioritize social benefit. As research becomes clearer about how much protection those who’ve already been infected have against the virus, or more is known about the role of children in spreading it, it may be possible to prioritize reopening daycares or schools, for example — with the caveat that teachers or students with underlying conditions may need to stick with distance learning. Likewise, some businesses might be able to partially re-open, perhaps on certain days, or for certain hours, with mandatory hand sanitizing and temperature checks at the door. “There are ways to do this, to loosen that faucet gradually,” Frieden said.

- Be ready to reinstate restrictions quickly if needed. “One thing we’ve learned is that it’s about one week, at maximum, between the time when cases begin spreading in the community until it explodes,” Frieden said. “If you don’t act in that week, you’re going to be behind the 8-ball.” The public health community needs to be ready to test patients, trace contacts immediately, and continue to promptly isolate those who are ill and quarantine people they’ve been in contact with effectively, Frieden said. “You’ll need to be prepared to tighten the faucet right back up, quickly, if you need to.”

Find slides from Dr. Frieden’s presentation to mayors here.