Making revenue collections more effective: lessons from a Nobel laureate

Making revenue collections more effective: Lessons from a Nobel laureate

Last month, Richard Thaler was awarded the Nobel Prize in economics for his contributions to the field of behavioral economics. While much of the coverage focused on his pioneering research integrating insights from psychology about the limits of human rationality to economics, cities across the globe are reaping the benefits of the behavioral science revolution.

As Bloomberg Cities and others have documented, cities are increasingly applying behavioral science insights to make government more effective, efficient, and accessible. One particularly important arena these innovations are impacting is city revenue collection.

For many cities, collecting the tax and fee revenue required to provide services is a vital, but often-challenging necessity. Even small improvements in revenue collection could make a noticeable difference, but the costs — both financial and social — often outweigh the benefits of doing so.

With the support of Bloomberg Philanthropies, What Works Cities, and the Behavioural Insights Team (BIT) teamed up to implement behavioral science techniques in a variety of contexts. Several cities decided to use this opportunity to focus on improving the collection of overdue bills.

Chattanooga, TN, and Lexington, KY, focused on the thousands of residents with overdue sewer bills. Hartford, CT, worked to increase the number of people paying their parking tickets.

Chattanooga and Lexington deploy courtesy letters and emphasize choice

The magnitude of uncollected sewer bills was a serious problem — Chattanooga had more than $5 million outstanding across about 12,000 accounts that were between 16 and 75 days overdue; Lexington had more than 7,000 accounts overdue by 61 days or more, totaling about $4 million.

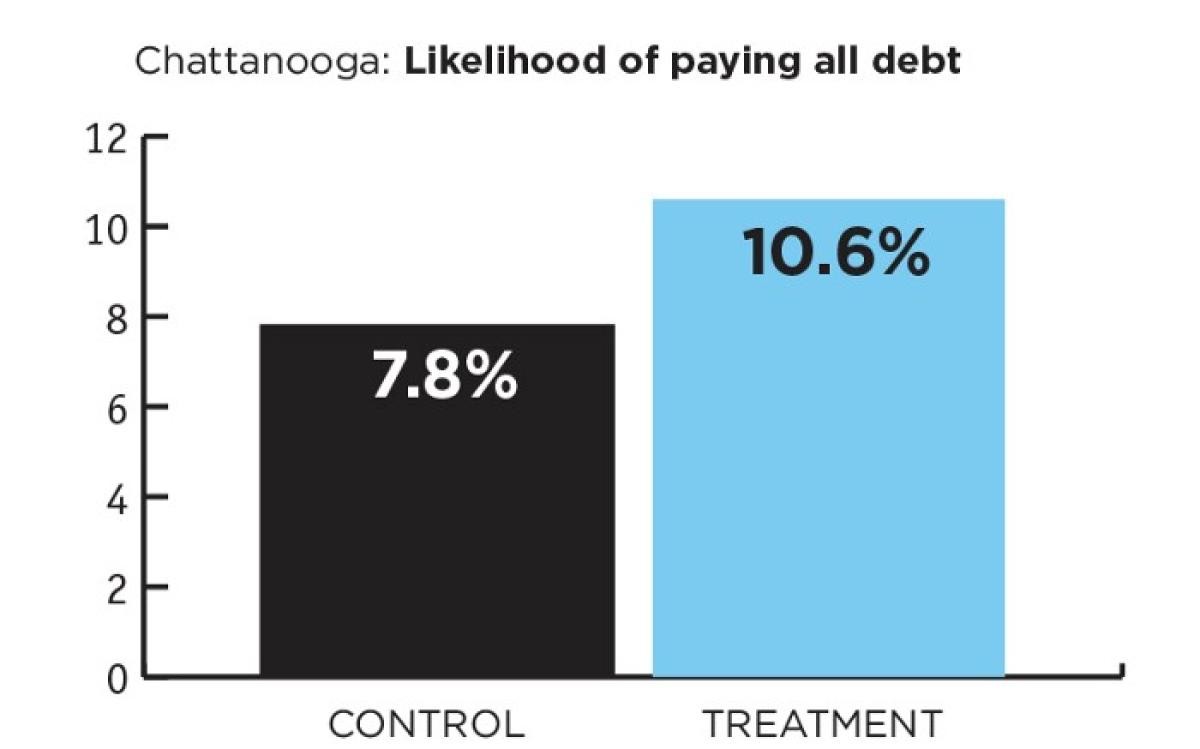

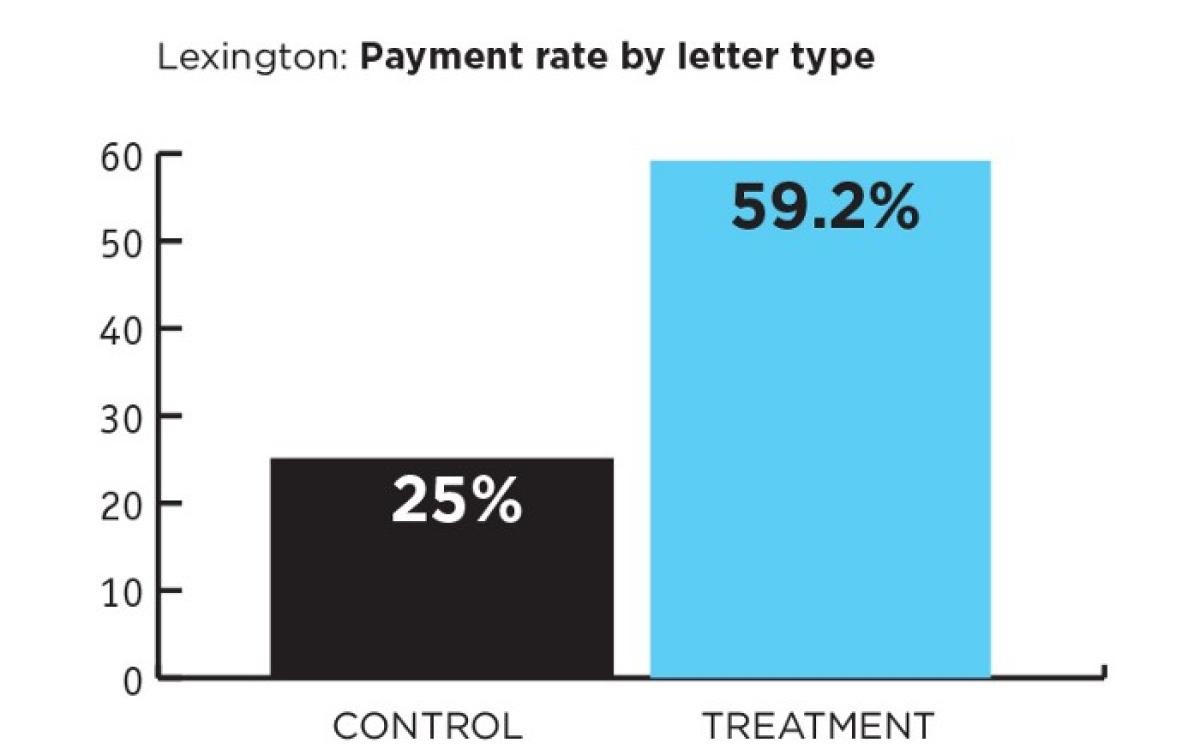

With the help of BIT, both cities conducted a similar experiment in early 2016: the cities sent a courtesy letter to some of the delinquent accounts warning recipients that they were on a list of residents whose water could be disconnected. It contained clear payment instructions, a “pay now” image and a message declaring that not responding will be treated “as a deliberate choice.” The other residents just received the standard bill, which noted payments were overdue.

Among those who received the courtesy letter, Chattanooga saw a 36 percent increase in the share of accounts that paid all their debt, and a 12 percent increase in the share of accounts that made any payment. Sending the letters yielded an average $13 in revenue per letter sent.

Michael Baskin, Chattanooga’s chief policy officer, saw the program as a win-win. “From a city perspective, our option was to disconnect a bunch of people, which we really weren’t super-excited about. None of us got into government to cut people’s water off,” he said. “Also, that’s an expensive process for us … and from a fairness and equity standpoint, we hadn’t been clear about repercussions in the past.”

Lexington saw even more dramatic results from a similar strategy, with the rate of payment increasing by more than 100 percent in the first month; even when viewed over three months, the letters increased the share of those who made a payment by more than 75 percent. The city saw a return of more than $90 on average per letter sent; adding a handwritten note to the envelope made the letters even more effective.

Hartford uses social norms to collect parking ticket payments

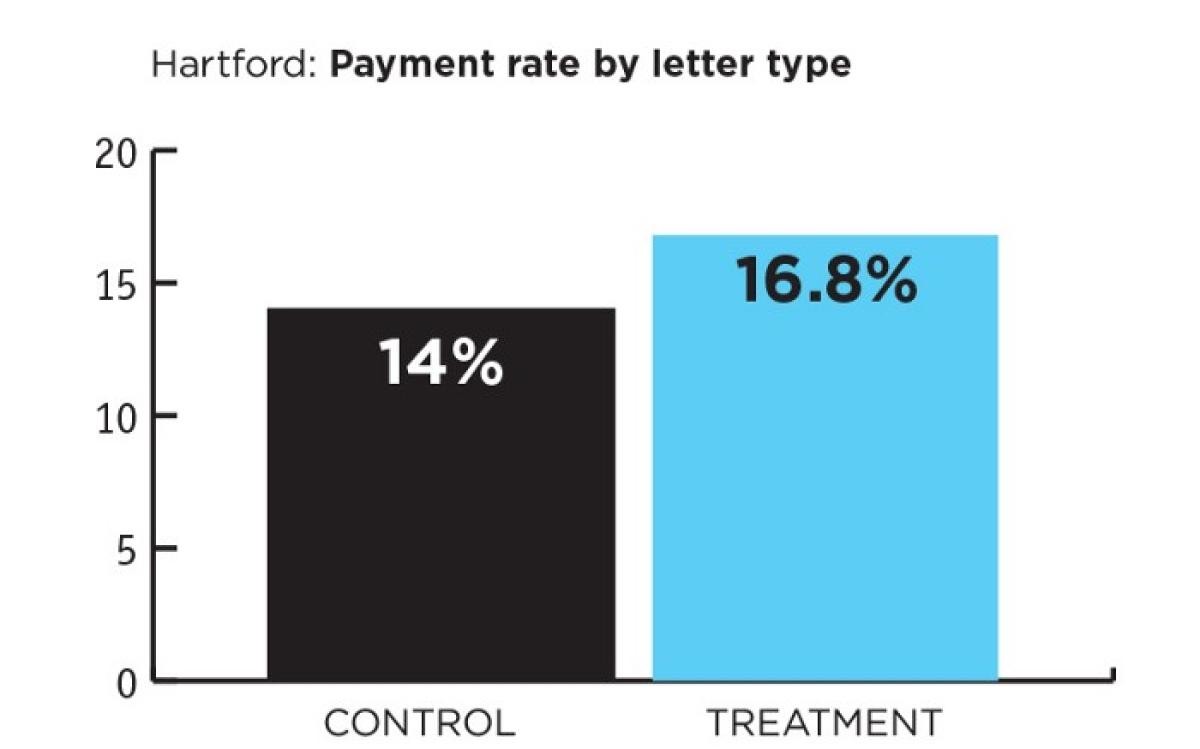

Hartford took on a different challenge: unpaid parking tickets. With the help of BIT, the city’s parking authority redesigned its overdue notice to simplify it, display an easy way to pay, and include a clear call to action. It also told recipients, “The majority of drivers who receive a parking fine in Hartford pay it within 30 days.” Half of households during the experiment, which ran from February through April of this year, got the new, redesigned letter; the other half got the one the parking authority had already been sending.

The redesigned letter was the clear winner: it increased the likelihood recipients paid a parking ticket by about 20 percent, bringing in more than $4 extra on average per letter sent. According to the BIT’s estimates, the city could collect nearly $130,000 extra a year without spending an extra dollar by sending the improved letter to everyone eligible.

“I was looking for maybe a single digit increase,” said Eric Boone, Hartford Parking Authority CEO. “To get a relative 20 percent [increase] … that’s pretty impressive.”

Building on success

These experiments, while relatively small in initial scale, could offer a promising model for other cities. “We’ve stuck with the new letter,” Hartford’s Boone said. “And we’re looking to expand what BIT did to the rest of our letter suite.” He said that the parking authority hoped to make similar tweaks to the second-notice letter, a collections letter, and potentially even the parking citations themselves.

In Hartford and Chattanooga, decisions are still pending about future use of the BIT-sparked strategy.

Chattanooga’s Baskin emphasized, however, that no matter how the city uses the technique in the future, the experiment with overdue sewer bills was easy to implement and valuable. “From ideation to go, it was roughly two weeks — it was really easy,” he said. Hartford’s trial took more planning and technical development, but the participation of the city’s vendor, Municipal Citation Solutions, means more than a dozen other cities could conduct a similar randomized control trial if they are interested.

The cities involved saw an important lesson in this work: Making it easier for citizens to fulfill their obligations was good for the cities too.

“All that we did was we looked at a form, we looked at a letter, and we said, ‘How can we shape the path to make this easier for citizens to pay their bills?’” Baskin said. “The result was they paid more bills. If you make it easy, people will do it.” Boone concurred, noting for Hartford, “It’s not cost-effective to have to boot somebody — I would rather just have them come in the door.”

For cities that are struggling to balance budgets, these experiences may offer important lessons. Improving design, highlighting social norms, and emphasizing choices offer ways for cities to make life easier for their residents while also collecting more revenue.

Check out the Behavioral Insights Team’s “Behavioral Insights for Cities” report, which features many applications of behavioral science to city challenges.