Innovation in the Heartland: How Sioux Falls is turning public problem-solving on its head

When you first hear the backgrounds of the eclectic group of people working on transportation solutions in Sioux Falls, S.D., it sounds like the setup to a joke: What do a librarian, a fire captain, and a business analyst have to do with transportation?

But when you see this cross-departmental group huddled in its “War Room” working jointly with residents to fill up poster-size sheets of paper with ideas by the dozens, it’s clear that this is no joke. In fact, it could be the future of how City Hall teams work across silos to better solve problems.

One recent afternoon, the Sioux Falls group discussed ideas that were pretty novel for a mid-sized city where bus service is spotty and used, primarily, by those who can’t afford a car. They talked about how dynamic routing might reach more riders and improve the bus-riding experience. They brainstormed ways to leverage Lyft, the ridesharing service that arrived for the first time in Sioux Falls 18 months ago. And they explored how the city might engage employers, nonprofits, and housing developers in new ways to help people get from home to work and back.

Librarian Dan Neeves said he knew nothing about public transit when city leaders invited him to join the group. He’s overcome some initial apprehension to embrace the value he and the other transportation newbies bring as they flesh out ideas for the city to start piloting later this year. “I don’t have any preconceived notions,” Neeves said, “so I’m free to think widely.”

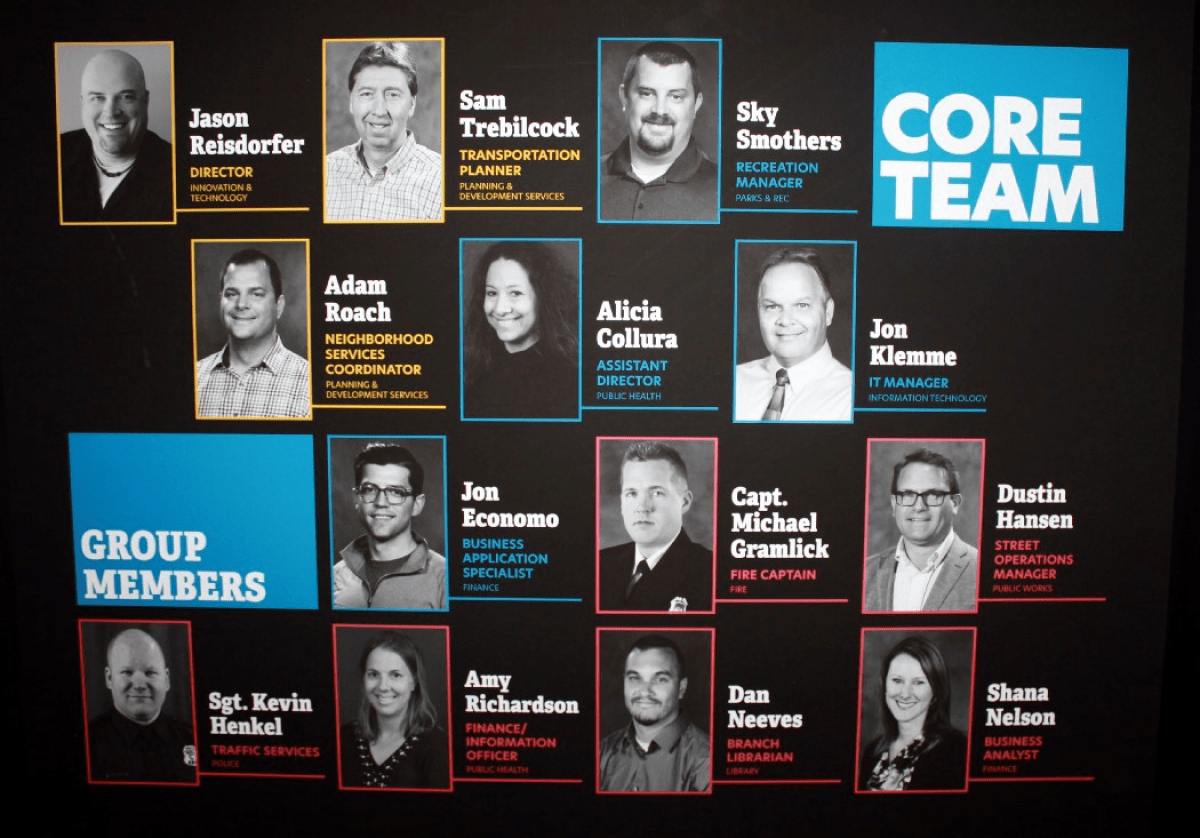

That’s exactly what Mayor Paul TenHaken had in mind four months ago when he pulled this group together. TenHaken is an entrepreneur who started a successful digital marketing business in Sioux Falls. Since he became mayor last May, he’s made a top priority of building a more innovative culture inside City Hall. The transportation group — what everyone simply calls the “Core Team” — is a good example of how he’s doing it.

“No one has a monopoly on good ideas in the city,” TenHaken said, noting that teams full of subject-area experts can get too mired in what they already know to think freely. “Sometimes, when you get people out of their lane, they’re more apt to come up with new ideas and strategies that never would have bubbled up before.”

Prioritizing innovation

TenHaken, 41, entered office with lots of ideas from his private-sector days about how to build an innovative culture. He said it all went into overdrive last summer. That’s when he joined 39 other mayors to kick off a yearlong executive training program through the Bloomberg Harvard City Leadership Initiative. TenHaken was struck by hearing other mayors talk about their innovation teams and chief innovation officers. Sioux Falls had nothing like that.

He went home and changed that almost immediately.

TenHaken busted up what had been a grab-bag department called Central Services, moving responsibility for things like the vehicle fleet and facilities management to other agencies. He rebranded what was left as the Department of Innovation and Technology, giving it a more strategic mission and recruiting Jason Reisdorfer, the operations director of another fast-growing local company, to lead it. Reisdorfer has just hired the city’s first-ever innovation coordinator to work across departments to deliver better results.

“We’ve got so many problems in the city that we were tackling the same way we did 10 years ago, and making two degrees of change,” TenHaken said. “That’s not enough.”

While the new department combines innovation and technology, TenHaken is clear that those two things are not the same. For example, he said, the city reshuffled the work and break schedules of its street-sweeping crews in a way that yielded two additional hours of service each week. “There’s no technology involved,” TenHaken said. “Innovation to me is finding new ways of solving old problems. It may or may not involve technology to get there.”

[Read: First-year mayors find executive training comes at the right time]

A lot of the culture change TenHaken is going for comes down to keeping the 1,300 people who work for the city motivated. One small but visible change: He’s adopted a more flexible dress code like what he saw in the private sector. City Hall employees are now told to “dress for your day,” which can mean jeans around the office, but more formal attire for business meetings.

TenHaken also reached out to city employees to help develop a set of core values for the organization. Those values — such as providing for the safety, health, and wellbeing of residents — are used as compass points for deciding who to hire or fire, or for guiding staff through tricky situations like the flooding that has hit the city this month. TenHaken calls these values “One Sioux Falls.”

One of the biggest things the mayor brought over from his private-sector days is a tool for measuring employee engagement. Every few weeks, city employees get a short survey and rate, on a scale of 1 to 10, things like whether they feel their opinions are heard at work, or whether they’re able to take a break when stressed. TenHaken gets dashboard scores for different agencies, giving him insights into where managers can improve. For example, after the Parks & Recreation Department scored low on communication with employees, leadership started holding quarterly meetings to give employees more insight into where the department is headed.

“That’s how you shift the culture,” TenHaken said. “A more engaged employee is a more productive employee.”

A pick-up team of creative minds

The most audacious piece of TenHaken’s innovation agenda is happening two blocks down the street from City Hall, on the third floor of a new city office building. That’s where the transportation Core Team meets every Friday for two hours over lunch.

The’ve set up their War Room in a cavernous unfinished corner of the building with huge windows, a raw ceiling with exposed steel beams and ductwork, and a shiny gray concrete floor. Most of the vertical spaces, from the walls to the windows to the bulletin boards erected on huge wooden stands, are colorfully plastered in sticky notes.

[Read: Inside the Sioux Falls innovation ‘War Room’]

Jason Reisdorfer leads the 13-person team and worked with department directors to pick its members. “They were not to have specific knowledge of the public transit issue,” Reisdorfer said of the kinds of people he was looking for. “They had to be good innovative minds, strategic thinkers, and high-energy folks — not the sort of people who would say, ‘But this is how we’ve always done it’.”

The result is a sort of pick-up team of creative people from across local government. Departments represented include Finance, Fire, Innovation & Technology, Library, Parks & Recreation, Planning & Development, Police, Public Health, and Public Works—there’s one transportation planner on the team, who is able to inject subject-matter expertise when it’s needed. Core Team members dedicate three to five hours a week to the project, alongside their day jobs.

[Read: Three tips on cross-sector collaboration]

The method they’re using to tackle transportation in Sioux Falls is called “human-centered design.” With coaching from Brianna Sylver, a Chicago-based designer on assignment with Bloomberg Philanthropies, the Core Team is trying to flip the script of how local government handles problem solving.

The idea is to approach transportation without any assumptions about what’s broken or how to fix it. That’s really hard to do in a city like Sioux Falls, where obvious holes in the system — such as a lack of bus service on Sundays — can descend quickly into old and hardened debates about whether there’s enough money to fund new service or enough riders to justify it.

Instead, the team is taking a more open-ended approach. Before jumping to solutions, they worked to deeply understand transportation problems in Sioux Falls, from the perspectives of the people impacted by it. The Core Team identified stakeholders such as bus riders, employers, and people who don’t ride the bus. And they split up to interview dozens of people from each stakeholder group, both out in the field and in conversations in the War Room.

Sky Smothers, a recreation manager with the Parks & Recreation Department, was one of a few team members who spent an afternoon riding city buses and interviewing passengers about their experiences. It was valuable to hear directly from riders about the city’s transit service, Smothers said. He also found the experience of riding the bus himself helped him better understand the needs of the people who ride it every day.

[Read: What is human-centered design?]

One morning, Smothers tried out riding the bus to work — a trip that usually takes 10 minutes by car took him an hour on the bus. He had to leave home earlier, forcing his wife to change her schedule in order to take care of their two young boys. On one bus ride, he found himself 50 cents short of the $1.50 fare, which has to be paid in cash, with exact change. “It really opens your eyes to the challenges people face riding the bus,” Smothers said. “If you just sat in your office, you wouldn’t know it because you would not be experiencing it.”

‘Everyone is excited’

Following their field research, the Core Team assembled in the War Room. They scribbled hundreds of takeaways both big and small on sticky notes. Looking for patterns in what they’d learned, they synthesized key insights such as how long bus rides take, or the potential for public-private partnerships to fill service gaps. Along the way, they held their tongues when solutions came to mind — they needed to understand the problem first.

Meeting with the team a couple of weeks ago, Sylver acknowledged that’s hard to do.

“One of the biggest things people struggle with in a human-centered design approach to problem solving is that it feels like you take a long road to get where everyone wants to start,” she explained. “Albert Einstein once said if he had eight hours to solve a problem, he’d spend seven hours trying to understand it and an hour solving it.”

On this day, the team began moving toward solutions, through a process called “ideation.” Four Sioux Falls residents, including one who uses a wheelchair, joined them. Seated in small groups around tables covered in brown butcher paper they could draw on, they bounced ideas off each other and built on one another’s thoughts. In two hours, more than 50 ideas for improving transportation service came tumbling out; at the end, everyone voted on which ideas they liked best by placing round stickers next to their favorites.

It’s still early days for the Sioux Falls Core Team. They have more ideation sessions to come, and many more ideas to generate with residents. Later, they’ll pick ideas to prototype, and test out those prototypes with residents. That will give the team quick but concrete feedback they can use to tweak their ideas before the city invests real money or time in any particular solution.

[Read: Prototyping city solutions and launching a revolution]

What the group produces probably won’t look like one “silver bullet” idea that solves the city’s transportation woes once and for all. It may instead involve a number of fixes, each aimed at different pain points in the transportation system. By the time Sioux Falls is ready to start piloting some solutions this summer, they’ll have confidence that they’re on to ideas that respond to real needs in the community, are likely to work, and represent innovation for Sioux Falls and its residents.

For members of the Core Team, the experience so far has been uniquely energizing in their careers as public servants. Several said this is their first time working with people in other departments. Others said it’s exciting to work on something the mayor has made a high priority. They value the direct contact they get with him when he drops in on their meetings or posts a note to the group’s instant messaging channel on Slack.

“It’s invigorating to work outside your department,” said Amy Richardson, a finance and information officer with the Public Health Department. “There’s new personalities, new ideas, and no judgement about whether your ideas are good or bad. The whole point is just to get it out on the table. Everyone is excited — you can feel it.”

TenHaken’s hope is that each member of the Core Team will take that excitement back to their own departments and spread these new ways of thinking about problem-solving throughout local government. While the issue today is transportation, TenHaken thinks the model of building cross-departmental teams can help solve any big problem cities face today.

“Each of those departments has a transportation-esque problem they’ve been staring at for years and not doing anything about,” TenHaken said. “A process like this brings brand new life and energy into finding a solution.”