How to fight COVID-19 in jails

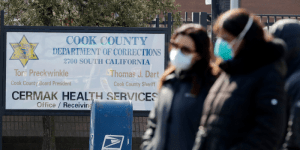

As alarming as the COVID-19 outbreak is in almost every corner of the country, it’s especially so in the nation’s prisons and jails. Just consider that, Chicago’s Cook County Jail alone, more than 500 people have tested positive for the virus — with detainees making up two-thirds of the cases — and at least three people have died. Similar scenarios in Houston, New York City, and almost every other U.S. city and town make it painfully clear that people behind bars and the staff who work with them are at particularly high risk for infection. Close quarters in crowded facilities make social distancing difficult, if not impossible, to enforce.

To address this quickly developing concern, The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health on Tuesday issued new recommendations to help ensure safety in local jails and other incarceration settings like state prisons or juvenile detention centers. What’s needed is “a concerted, state and local government-supervised strategy across facilities,” the report states, as well as “meaningful, centralized oversight.”

Specifically, the guidance contains four recommendations for decision makers:

1. Increase transparency. Incarceration sites should make their COVID-19 response plans, as well as the number of cases, deaths, and other data, publicly available. “Without knowing the content of these plans or circumstances unfolding in these settings,” the report says, “it is difficult to discern risk for transmission or for public health officials to provide guidance on measures that need to be taken to ensure safety.”

- See the Bergen County, N.J. jail’s COVID-19 data here.

- See the San Francisco Sheriff’s Office’s COVID-19 response and action plan here.

2. Reduce density of incarcerated people. The report recommends early release for inmates over age 55 and those with underlying conditions when possible, and stepping up use of community-based incarceration alternatives. Reducing crowding this way “makes it more feasible to implement social distancing practices,” the report says, while relieving burdens on strained staff. These steps must be paired with help for released individuals with finding housing and food, as well as steps to free up parole supervision capacity.

- See the Prison Policy Project’s roundup of local actions on early releases.

3. Reduce risk of transmission. Hygiene basics like handwashing aren’t always so easy to practice in correctional facilities — in some, inmates must buy their own soap and alcohol-based hand sanitizer is prohibited. The guidance says to enable frequent handwashing, and step up education about the importance of hand hygiene and social distancing. Facilities also are urged to step up inmates’ access to health care and to proactively communicate with hospitals about virus exposures and infections.

- See county jail inmates in Wichita, Kan., must wear masks

4. Protect mental health of incarcerated individuals. With family-and-friend visits no longer an option, the report suggests correctional facilities step up the use of video visitations and attorney meetings. It also cautions that individuals requiring isolation or quarantine not be made to feel that they are being disciplined or put in “solitary confinement.”

- See new video visitation setup in Dayton, Ohio’s county jail

Read the full Johns Hopkins guidance on protecting incarcerated individuals report here.

Read the CDC’s interim guidance for correctional and detention facilities here.