How Detroit’s new food-delivery pilot is helping ‘box-in’ COVID-19

Imagine for a moment: You’ve just been diagnosed with COVID-19. You’ve been told to self-isolate at home, and you don’t have friends or family nearby to call for help.

How are you going to get groceries?

Detroit is piloting a food-delivery program for people in exactly this situation. It’s not only helping solve one part of the city’s hunger problem at a time when food supply chains are scrambled and pantries are slammed. It’s also helping stop the spread of the virus by enabling infected residents to stay in isolation — one of the four things cities need to do to “box in” the virus and finally get COVID-19 under control.

“People get that COVID-19 positive diagnosis and then are told they can’t leave their house, and their world is absolutely rocked,” said Alicia Moon, director of the city’s innovation team, which coordinates the program. “Residents are crying on the phone with our team saying, ‘I don’t have friends or family here — I don’t know how I would’ve fed myself if you hadn’t offered to drop off food.’”

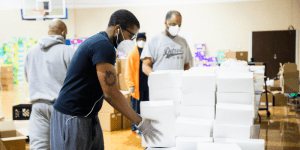

Detroit’s pilot is built on the combined efforts of staff from several city departments, external partners who provide the food and support, and more than 100 volunteers who deliver boxes of meals from their cars every Wednesday. So far, they’ve served more than 30,000 meals to over 600 people, and they’re now plotting how to scale that up significantly. The effort targeted at COVID-positive residents stands alongside a substantial operation the city has built where residents in need can go to pick up their own meals, as well as an interactive map the city designed to help residents find food pantries.

For City Hall, building a food delivery network from scratch represents not one innovation but several stacked one atop another. Here’s some of the ingredients of how Detroit did it:

Inter-departmental collaboration. The food delivery program is a combined effort of a number of departments, including Health, Housing & Revitalization, Neighborhoods, Parks & Recreation, different groups within the Mayor’s office, and a “LEAN team” that specializes in process-improvement. Many staff are working outside their normal roles. For example, Parks & Rec staff who normally run basketball camps or aquatics programs are now boxing food for delivery. “The ability of people to rapidly change focus and not stay in their silos has been remarkable,” Moon said.

City Hall can’t do it all. External partnerships are also critical to the program, from the relief organizations supplying food to the churches, labor unions, and youth groups who have brought volunteer muscle to the operation. In surveys of volunteers, 100 percent have said they would recommend the program to a friend as a volunteer opportunity. “Volunteers are telling us they like that it’s a way they can come out and help without being in direct contact with other people,” said Breanna Sullivan, Volunteer Coordinator for the Department of Neighborhoods. “In a time of social distancing, they feel like this brings connection.”

Just do it. City staff recognized that the urgency of the moment required immediate action. They cast aside the normal urges to make the program work perfectly from the start and embraced a philosophy of continuous improvement. “Standing up something like this feels really intimidating, and it’s a heavy lift,” said Erin Casey, Assistant Director of the Parks & Recreation Department, which is coordinating food procurement and packing it up for delivery. “Everyone went into this knowing that the intention is to serve people and recognizing that at first it’s going to be a little bit bumpy. But knowing that it’s OK as long as we’re working to improve along the way.”

Pivoting with purpose. Organizers have made numerous adjustments as the program developed. For example, the i-team developed a digital training process for volunteers and updated those materials several times based on how it’s working. It started out as a recorded Zoom presentation of a slide deck. Now, there’s a more interactive training that includes videos of the entire volunteer experience, from driving to pick up the food to showing where to leave food on a resident’s porch. Now, there’s an automated quiz that asks four simple questions about the most important things volunteers need to know. “There’s been a lot of pivoting,” Moon said. “It’s not just doing one thing and sticking with it but changing constantly to meet the need.”

Make it easy for people. Social services often require beneficiaries to navigate tons of red tape. This program isn’t like that. “We’ve been really intentional about just trusting people and saying: ‘If you tell us you need food, we believe you and we’re going to get it to you right away,’” Casey said. “It’s shifting the narrative a lot of folks we’re serving previously had about government to one where we’re saying, ‘here’s something really concrete we can do to support you right now that’s going to make a huge impact in your life.’”