How a card game can help city residents suggest new ideas

This year, Helsinki is embarking on a bold experiment in direct democracy. For the first time, municipal leaders are putting aside part of the city budget and empowering residents to decide for themselves how those funds should be spent.

Helsinki is not the first city to try its hand at “participatory budgeting.” The strategy goes back 30 years to Porto Alegre, Brazil, and spread across Latin America, Africa, and Asia before jumping more recently to European cities such as Barcelona and Paris, as well as American cities such as Boston, New York, and Oakland.

But Helsinki has added some new twists. Most notably, city leaders — working closely with residents and a local design firm — developed a card game to help people come up with ideas for how to spend their share of the budget. It’s a kind of gamification of citizen engagement that Helsinki has become well known for — and something cities everywhere can learn from, whether they use participatory budgeting or not.

For Helsinki, it’s all one piece of a major local-government overhaul intended to make City Hall more responsive to the public. There’s more power vested in local leaders, including Mayor Jan Vapaavuori, who has pledged to make Helsinki the “most functional city in the world.” The city also has created a new team of seven “borough liaisons” to promote citizen participation in each section of the city.

Participatory budgeting weaves through all of that. Helsinki has set aside €4.4 million (roughly $5 million in the U.S.) for residents to use as they wish. While that’s just a fraction of the city’s €4 billion budget, it’s enough to fund dozens of small but locally impactful projects like new playgrounds or bus shelters. It also represents an entirely new way to get residents engaged and thinking about how they can improve their city.

Engagement isn’t automatic, however. As the Helsinki team developed their plans, they interviewed residents — using techniques of human-centered design — to understand how people felt about participatory budgeting. While they found a lot of excitement, they also heard concern that the process of proposing ideas seemed daunting or overwhelming. “It’s not easy to just come up with ideas,” said Kirsi Verkka, who manages participatory budgeting for Helsinki. “People need encouragement to participate and get engaged.”

That’s where the card game comes in. The game is aimed at making it easy to come up with and submit ideas for funding — less like a civic duty and more like a fun thing you do with friends and neighbors. That, too, comes from the discipline of design, where there’s an emphasis on finding creative ways to solve problems in new ways.

“The game is a tool to make it approachable,” Verkka said. “Not something that feels complex or bureaucratic, but something where you can sit down with people, have a good time, and do something for your community.”

At the same time, the game serves another purpose: To help residents make strong proposals that solve real community problems. The game also encourages players to consider not just how their idea improves their own lives, but also the lives of others.

[Read: How Helsinki uses a board game to promote public participation]

Hundreds of Helsinki residents have played the game in workshops hosted by Verkka’s team. More have played in informal gatherings: Verkka has given away more than 300 sets of the game materials, consisting of a deck of 40 cards and instructions for how to play. “Giving it away has been one of our marketing tools,” she said. “We want people to play in their own groups and communities.”

(The materials are published under a Creative Commons license; You can download an English version of the cards here and the instructions in English here.)

Play takes up to 90 minutes and happens in small groups — Verkka said seven people is a good size. Players divvy up roles such as director, scribe and timekeeper. (You can watch the following video learn how to play.)

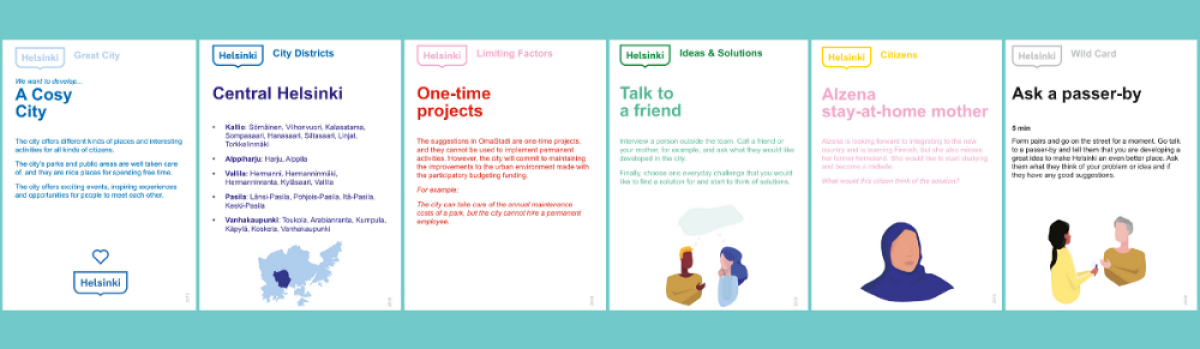

The game centers around six different kinds of playing cards, each tailored to spark conversation among players to ignite ideas and give them shape:

- Light blue “Great City” cards are about different ways Helsinki can improve, by developing spaces like parks where people can meet, for example, or making the city safer.

- Dark blue “City Districts” cards are about scale: Is the idea intended for the whole city or just for a certain neighborhood?

- Red “Limiting Factors” cards set parameters: Projects must be one-time activities rather than ongoing commitments, and can’t exceed a cost of €35,000; they also can’t contradict core city values such as promoting equality, safety, or sustainability, or fall outside the city’s legal jurisdiction.

- Yellow “Citizens” cards offer personas of different Helsinki residents to keep in mind as potential users of the project: for example, stay-at-home moms who are recent immigrants to Finland, students, or persons with reduced mobility.

- Green “Ideas & Solutions” cards get people thinking outside the box. Draw one of these cards, and you may be told to call a friend or family member to ask what they would like developed in the city, or to write down an idea on paper, hand it to the person to your left and have them develop it further.

- Black “Wild” cards are for when a team gets stuck or locked in an argument. These cards encourage everyone to take a short break, or even pop out onto the street and bounce their idea off a person walking by for feedback.

After pitching ideas, debating, and developing them, players decide among themselves which ideas to formally propose and submit them to the city’s web-based participatory budgeting platform. That’s the end of the game — but just the beginning of the road for residents’ ideas.

The city received a total of 1,260 ideas from residents while the call for submissions was open for three weeks last fall. All the proposals were then sent to city departments for vetting, to make sure they followed the city’s rules; about two-thirds of those ideas made the cut.

[Read: How Helsinki’s new library prepares residents for technology’s future]

Now, the city is hosting a series of co-creation workshops. These are public forums where residents break into committees to analyze all the ideas for a similar topic — cultural events, for example — and assemble those ideas into a plan. This spring, those plans will go back to city departments to receive cost estimates. Later, residents will vote on which plans they want to see implemented.

Verkka said she presented the game recently at an international conference in Berlin and found other cities were very interested in the strategy. “It’s a tool that makes this whole participatory budgeting thing more approachable,” she said. “It’s easier to get your hands around it with a game. It’s a really complex thing, but this game makes it more approachable and more doable.”