Expert: How cities should prepare for a season of dual disasters

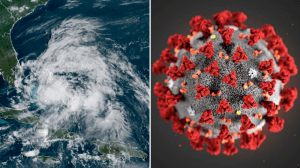

As Tropical Storm Isaias lashes the East Coast from Florida to Maine this week, following half a dozen other storms to already impact the U.S., the 2020 hurricane season is turning out to be a busy one, as predicted. Meanwhile, wildfire season in the West is in full swing, with 10 large fires burning in California, nine in Alaska, and more in Arizona, Nevada, and a number of other states.

All this on top of a pandemic.

This “dual disasters” scenario is one that city leaders have been worried about for months. A June survey of American mayors by Bloomberg Philanthropies and the U.S. Conference of Mayors found that 69 percent were more concerned than in other years about their ability to respond to a natural disaster or other emergency striking their city this summer. And that was before a surge of COVID-19 cases across the South and West put new strains on first responders, crisis managers, and hospitals.

Now, the reality of managing two disasters at once has arrived in many parts of the U.S. Across Florida, the state with the highest number of confirmed COVID-19 cases for the past week, testing locations have been closed for days due to Tropical Storm Isaias. Evacuation shelters are screening people for coronavirus before letting them in, and operating at far reduced capacities to allow room for social distancing.

The good news so far is that there’s yet to be a “big one” natural disaster to hit on top of the pandemic. The bad news? It’s still early August. A lot can still happen.

To learn more about what mayors and city leaders need to keep in mind here, Bloomberg Cities caught up with Harvard University Professor Juliette Kayyem. She played top roles in the Obama Administration managing crises such as the H1N1 pandemic and BP oil spill. Kayyem also has been a frequent presenter in regular coaching and learning sessions for mayors and local leaders as part of the Bloomberg Philanthropies COVID-19 Local Response Initiative.

Kayyem said mayors are going to have to “add a COVID layer” to what they already know about communicating and managing the most common disaster situations where they live. And they’ll need to do it at a time when the public safety community and residents they serve are suffering from crisis fatigue. “I talk to a lot of first responders, am involved in the Red Cross, and people are exhausted,” Kayyem said. “From the top, no matter how frustrated the mayor is, there has to be some bandwidth for goodwill right now.”

Here are three more things Kayyem said mayors should keep in mind:

Know the plan. The local response to a wildfire or hurricane, just like COVID-19, requires intense collaboration with county, state, and federal authorities. The first step for mayors is to get familiar with how plans and preparations are changing for the pandemic — both where they are and also in surrounding areas in the event that an evacuation sends people fleeing.

For example, with limited shelter capacity available, local leaders will want to prepare residents to be ready to stay home, where that’s a safe option. Where it isn’t safe to stay put, they’ll want to encourage residents to pack a face mask and sanitizer and find a hotel or stay with friends or relatives. “You have to think through non-shelter alternatives to relieve the stress on shelter capacity,” Kayyem said.

“There’s some COVID risk involved in that,” Kayyem continued, “but there are no ideal answers when you’re dealing with COVID and another potential disaster. At this stage, you’re just weighing one risk against the other.”

Extend the runway. Where evacuations are deemed necessary, Kayyem said, it is likely they’ll be called earlier. In part, that’s because people have been told to stay home for five months, and some may be more reluctant to go as a result. “It’s going to be that much harder for people to evacuate,” Kayyem said. “And so mayors have to be aware of that.”

Protect evacuees. While mass sheltering is a last resort, the Red Cross and other shelter operators are working on ways to do it safely in the pandemic. More hotels and dormitories will be used. And where school gyms or community centers must be deployed, residents will need to get temperature checks at the door, there will need to be lots of space between families, and everyone working and staying at the shelter will need to wear masks. “Mayors need to communicate every individual’s responsibility if they enter a sheltering facility,” Kayyem said.

For more information:

- Public Disaster Shelters & COVID-19 (CDC)

- COVID-19 Pandemic Operational Guidance for the 2020 Hurricane Season (FEMA)

- Tornado Sheltering Guidelines during COVID-19 (American Meteorological Society)