Economic mobility: Why cities are stepping up to the challenge

What will it take to ensure that more people move up the economic ladder and achieve the “American Dream”?

That’s a question usually discussed among government leaders at the federal and state levels, where overarching decisions about tax policy and wealth distribution are made. But increasingly, mayors and other local leaders are not only engaging in the discussion about economic mobility but also looking to deliver concrete solutions to lift their residents up.

A new initiative launched yesterday aims to accelerate this local action in nine cities: Cincinnati, Ohio; Dayton, Ohio; Detroit; Lansing, Mich.; New Orleans; Newark, N.J.; Racine, Wis.; Rochester, N.Y.; and Tulsa, Okla.

Over the next 18 months, these cities will be identifying, piloting, and measuring the impact of a variety of interventions, with a goal of building the evidence base of what city-level policies and programs work and can potentially scale up. The project is managed by What Works Cities, a Bloomberg Philanthropies initiative that helps cities improve their use of data and evidence to make decisions and deliver better outcomes for residents. And it builds on research by Harvard economist Raj Chetty, whose “Opportunity Atlas” gives city leaders across the U.S. a more detailed view of economic mobility than they have ever seen before.

To learn more about what this new effort means for city leaders, Bloomberg Cities caught up with Chetty and Andrea Coleman of the Bloomberg Philanthropies Government Innovation team. Here’s what they had to say.

Andrea Coleman: Raj, the work you and your team are doing has brought the issue of economic mobility front and center in cities right now. What does your research show and why is it important for local leaders to pay attention?

Raj Chetty: Our team has been using big data in various forms to study one measure of the American Dream: the idea of upward mobility. In America, we believe that all kids, no matter their circumstances, should have a shot at climbing that ladder. And so we’re essentially assessing the extent to which that’s true.

For kids born in the 1940s and ’50s, there was a virtual guarantee that they were going to move up and have a better standard of living than their parents — 80 percent to 90 percent of kids born at that time went on to earn more than their parents. But when you look at kids who are entering the labor market today, that number is closer to 50 percent. So, in a sense, the American Dream really has faded over the past 50 or 60 years. And we’re broadly interested in studying why that’s the case.

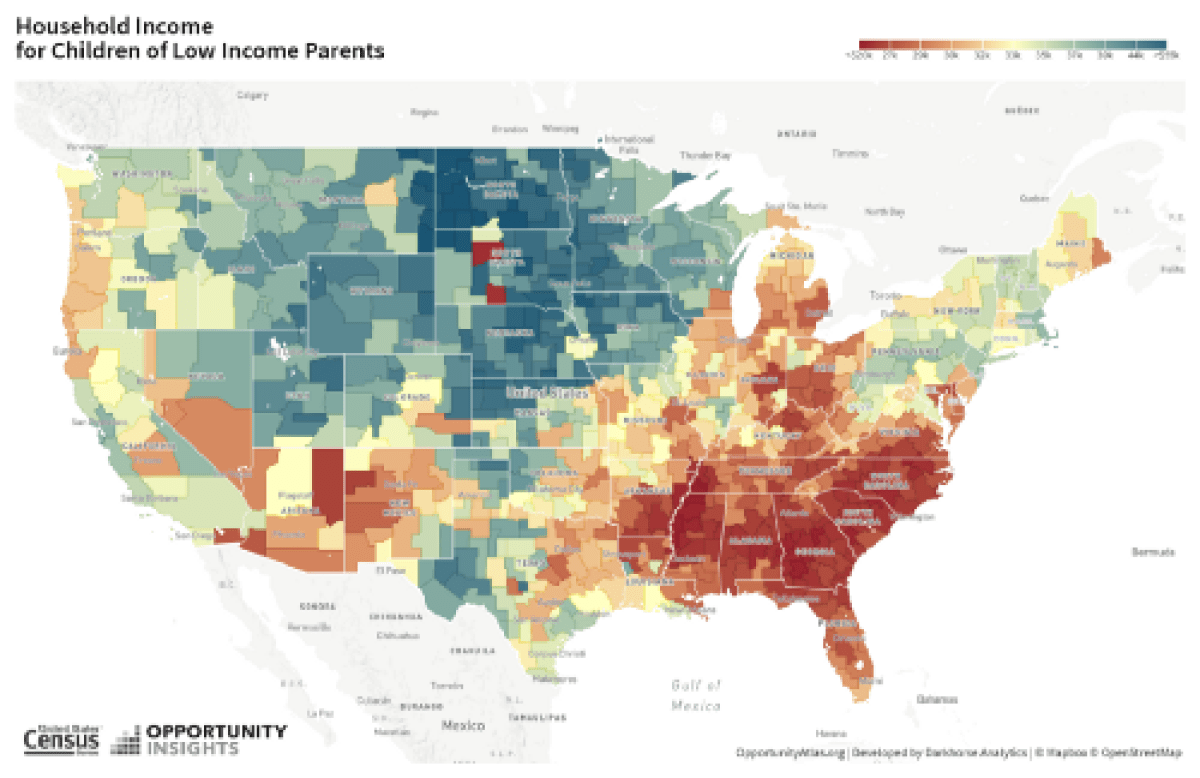

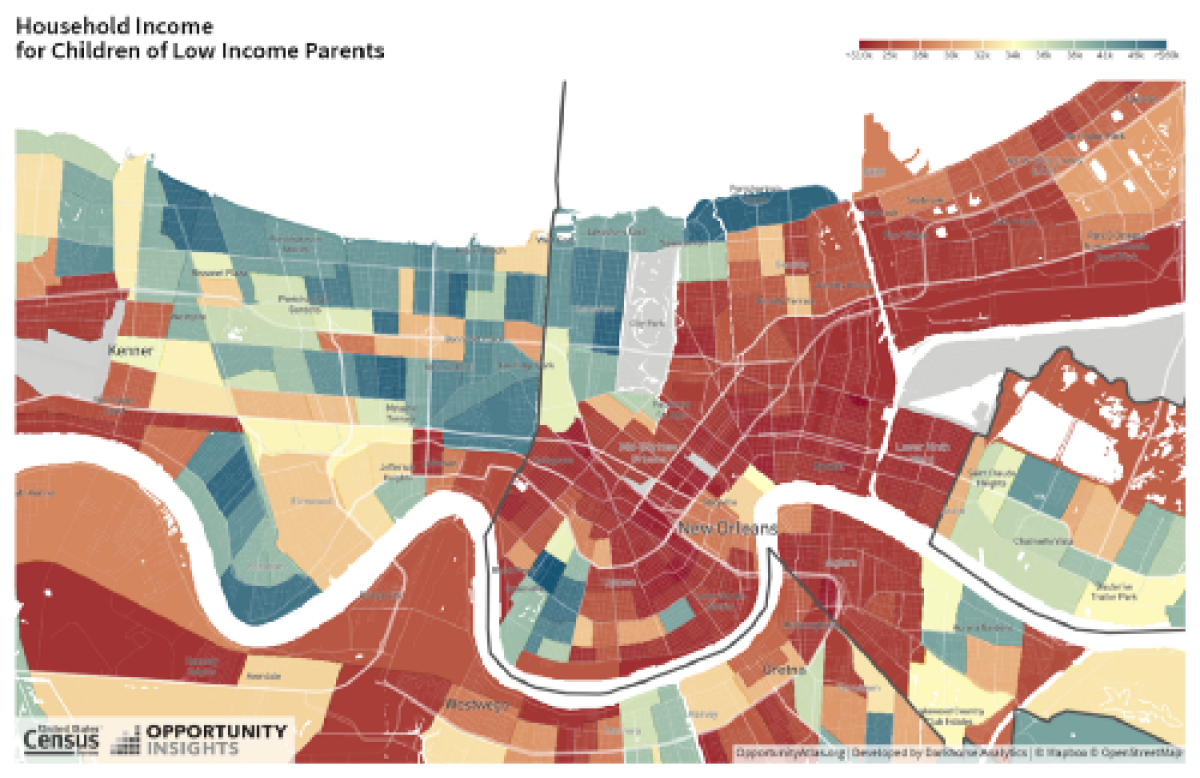

The reason this work is taking us to cities is that we find that the extent to which the American Dream has faded — or the extent to which kids will be able to climb the income ladder — varies greatly from city to city and even from neighborhood to neighborhood within cities.

So, when you look at Detroit or Charlotte, N.C., you’ll see that there are some parts of the city where kids who grow up there have really good chances at climbing up. You’ll also find that there are other parts where they don’t. While we’ve traditionally thought of the American Dream as a national issue, its roots really emerge at the local level, which is why cities can play a big role in reviving it.

A.C.: Your point about the importance of the local context really resonates. Your data visualizations showing that children’s outcomes in adulthood vary so sharply across neighborhoods that are just a mile or two apart are really powerful. It prompts a lot of questions about why that’s the case — and what cities and city leaders can do to maximize opportunities for children in all neighborhoods.

We know this is a top concern for mayors. In our 2018 American Mayors Survey, mayors said that providing better economic opportunities to all residents was one of their highest priorities. And we see it in the intensity of their interest in finding new and more effective interventions that address income inequality and economic mobility. Mayors hear about it anecdotally from constituents, they see it day to day in their cities, and now, with the work of your team at Opportunity Insights, there’s a strong research base behind that.

R.C.: We’re seeing that local interest as well. Charlotte, which I’ve already mentioned, is an especially interesting case because it’s a city with tremendous job and wage growth over the past 25 years. So by traditional economic measures, most people would think of Charlotte as an overwhelming success.

But when you look at the data on upward mobility for kids growing up there, you find that they actually have very poor prospects. So the way that adds up is that lots of people are moving to Charlotte to get those high-paying new jobs but, somehow, the local residents aren’t benefiting from that.

A.C.: That’s a very eye-opening point for mayors — that job growth doesn’t always translate into greater economic mobility. That should influence the way they think about what policies to pursue.

R.C.: Yes, and we’ve found that simply putting out these statistics is motivating to local leaders. There are two ways that cities can use the data. One is to make an assessment or diagnosis. Looking at data at a very granular level, you can begin to pinpoint exactly which parts of the city seem to be falling behind. And, often, you can learn about which demographic groups are not being served. It could be minority populations, or in some places, you find much better outcomes for women than men.

A second, more ambitious way to use the data — and this is where we’re excited to partner with cities through the What Works Cities initiative — is to figure out what sorts of interventions might make a difference. What sorts of policy changes might actually increase opportunity in the neighborhoods that are lagging behind.

A.C.: These 10 cities will be testing, refining, and piloting what we think are some of the most promising interventions — and then collecting data on what works and how. They’re looking at a broad-cross section of interventions, addressing different drivers of mobility, including early-childhood education, career readiness, financial empowerment, and housing.

[Read: Prototyping city solutions and launching a revolution]

This isn’t something that’s going to be solved overnight — or as a result of a single program or policy. But there’s a huge opportunity for these 10 cities to test interventions that target critical policy areas and share what they’re learning. By doing so, they’ll also be helping other cities across the country understand what some of the best strategies are. Getting good data — on what has worked or not worked in other contexts and why — is critical for cities to make faster progress.

R.C.: That’s exactly right. This capacity-building exercise is, itself, very important. Getting cities into the mindset of saying, “Here’s an important set of outcomes we should focus on,” and “Here’s how we can begin to think of potential policy solutions,” will help us create an architecture to take this issue on in an even bigger way going forward.

Another thing cities can do, which is completely actionable, is to use the money we’re already spending on affordable housing vouchers or the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit, and facilitate families to move to higher opportunity areas. We’re actually conducting such a trial in Seattle, called Creating Moves to Opportunity, in cooperation with Seattle and King County Housing Authorities. The results from this study will be out in about a month, and I can say now that they’re incredibly promising. We’re finding that you can dramatically change where families choose to live, voluntarily, using these housing vouchers in a way that will really reshape the next generation’s outcomes.

Of course, cities can’t possibly move everyone, and ultimately, they need to think how to invest in place and improve the lower opportunity areas. I find it useful to think about all of this as a pipeline of opportunity that begins at birth and ends when you enter the labor market, say in your mid 20s. And throughout that period, we want to build a strong pipeline of services.

[Read: new evidence helps more cities adopt Providence Talks model]

Starting at birth, you might think about things ranging from prenatal care to early childhood interventions. Then improving the quality of schools through a variety of different options from, say, hiring and retaining the most effective teachers to charter school-type solutions. And then, moving on through the pipeline, we find in a lot of our work that networks — mentoring, social capital, and social connectedness — all seem to be very important factors. So that means thinking about programs like Big Brothers Big Sisters that connect youth with mentors. And then going to higher education, think about making sure kids apply to colleges they’re qualified to get into — and making sure those colleges are admitting those students. So being thoughtful about that entire pipeline of opportunity in some of these disadvantaged neighborhoods is the second approach, that place-based approach.

A.C.: I love the pipeline analogy. And that’s something that we’re seeing from cities, interventions and touchpoints with residents along the way.

There are also challenges for cities in engaging in this work, and that’s something we’re focused on helping them overcome. Take your pipeline of opportunity, for example. City government often isn’t organized in this way. The work spans a lot of departments and funding streams and sometimes cities have difficulty connecting resources and getting the right people around the table to work on those solutions.

[Read: Lessons on cross-sector collaboration]

Also, we know that cities can have a difficult time measuring and tracking progress on these issues. And that can be for all sorts of reasons — whether it’s a lack of data, disorganized data, or capacity issues. Ensuring that cities are able to build their muscle around these data skills and strengthen their ability to measure progress along the way will be really important.

R.C.: What also makes this issue so challenging is that we’re talking about generational change. We’re talking about building human capital. In that pipeline, the time it’s going to take to see outcomes in terms of income, education, incarceration, and so forth is between 15 and 10 years. We need to be willing to stay the course, and wait for those outcomes to emerge.

What really gives me hope also brings us back to where we started this conversation. When you think about where we need to look in order to increase upward mobility, it’s not about imagining a totally different country or a completely different time period. Often, the answer is just down the street, where you see much better outcomes for kids from low-income families. That’s what gives me tremendous hope. It shows us that the solutions are already there. They’re literally there in our own cities. We just need to figure out how to scale them.

A.C.: I totally agree. And I’ll just build on it by saying that we know cities get better results faster when they share what they learn with each other. And in this cohort, we’ll have a group of cities working closely with each other to share lessons and experiences to advance the work. These models for collaboration can lead to better results on a host of issues down the road.