Cities make big bets in fight against homelessness

Last month, a survey of American mayors appeared to reveal deep pessimism about the fight against homelessness. Only 19 percent of mayors in the survey said they have much control over the problem, even though most said the public holds them accountable for it. A headline on the news site Axios summed up the findings this way: “Mayors feel powerless to reduce homelessness.”

However, there are mayors who would disagree with that conclusion. In fact, leaders in a number of cities, flush with federal dollars and armed with innovation tools fine-tuned through participation in Bloomberg Philanthropies initiatives such as What Works Cities, i-teams, the Bloomberg Harvard City Leadership Initiative, and others, are unlocking new ways of addressing the problem to produce better outcomes for residents.

Take Austin, Texas. Last April, a coalition of government, business, and nonprofit leaders there gathered to discuss what it would take to finally put an end to unsheltered homelessness locally. At the center of the wide-ranging plan they came up with was the need to secure or develop 3,000 housing units within three years. That’s a lot of housing in an expensive city. And it came with an intimidating price tag of $515 million.

Undaunted, local leaders began raising funds. The federal American Rescue Plan Act, or ARPA, provided a big boost. Calling the federal money a “once-in-a-lifetime” opportunity, Mayor Steve Adler rallied the city to put $107 million, the bulk of its federal allotment, toward the plan to end unsheltered homelessness.

Later, Travis County added another $110 million of its ARPA funds to the effort; more dollars have come in through various public, private, and philanthropic sources. Organizers still have more funds to raise to reach their goal, but they’re more than three-quarters of the way there.

[Have a question about federal assistance? Get answers and ask our experts here.]

Collaboration is key to how Austin is going about this. The cross-sector group driving the effort, which calls itself the Austin Homelessness Summit, recognizes that no individual organization in the city can generate impact at this scale on their own. It has to be a community-wide mission.

In addition to the housing units, the Austin initiative will need about 200 additional staff and a range of service providers to bundle social services needed to keep people housed. “We’re trying to help people collaborate and coordinate,” said Lynn Meredith, president of the MFI Foundation and chair of the Austin Homelessness Summit.

With funds entering the system and contracts mostly written, now the hard part begins, Meredith said. “We have to operationalize these dollars and turn them into stability for the people living outside,” she said. “Part of the issue we’re trying to solve is, who’s homeless, what do they need, and where can I find them? … We have a lot of work ahead of ourselves. How much money is going out, where’s it going, and what are the performance metrics?”

The Summit is attempting to funnel data on all of this into a system maintained by a housing organization called Austin Echo. That’s going to be critical to getting all the partners involved on the same page. “Lots of good work has been done before, but it has not kept up with demand,” Meredith said. “It needs to be coordinated; it needs to be collaborative .… What our stakeholders want to know is, how are you addressing this, where is the money being deployed, how is it being successful, and how are we pivoting when things are not successful?”

In Portland, Ore., city leaders also are making big investments in permanent supportive housing. Those projects will take some time to come online, however. In the meantime, they’re taking an innovative shelter experiment born in Portland 20 years ago and scaling it up.

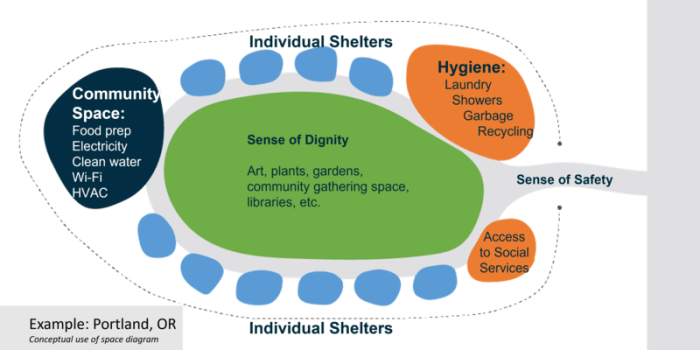

Essentially, it’s an outdoor shelter model where residents live in a cluster of “tiny houses." Portland’s first experiment with this idea, known as Dignity Village, showed how this model not only can work but build a sense of community. Now, city leaders are taking what they’ve learned and expanding on it with what they’re calling “Safe Rest Villages.” Each will have from 30 to 60 small dwellings co-located with social services as well as laundry, showers, and other basic amenities. The plan is to build six of them.

City officials had already made a zoning code change to enable the Safe Rest Villages to be built when an influx of federal aid arrived. “ARPA is the piece that allowed us to actually do the work,” said Chariti Li Montez, who manages the work for Commissioner Dan Ryan. Portland put $16 million—the single biggest outlay from its ARPA allocation—toward the project.

“Folks are going to be able to get stabilized and recover from the trauma of living on the street,” Montez said. “If you have a locking door, you can hold your possessions and go out to work and not worry about whether your tent will be there when you come back.”

In Chicago, the COVID-19 pandemic brought new urgency for city officials to think big—and innovatively—in finding ways to stem the city’s longstanding problem with homelessness.

In December, Mayor Lori Lightfoot announced a more than $1 billion investment in affordable housing. But in the meantime, leaders of the city’s division of homelessness services have been using data to increase the impact of money they’re already spending.

The division funds 75 percent of the city’s shelter beds through about 50 contracts with providers. Maura McCauley, deputy commissioner of homelessness services, said the existing procurement process was not focused on the result the city wanted to achieve—getting residents into permanent housing. “We had seen long lengths of stay in our shelter systems,” McCauley said. “Movement into permanent housing felt relatively low to us.”

The division partnered with the Government Performance Lab at Harvard University to overhaul its procurement practices. In 2018, they piloted a contracting process that was much more explicit and transparent in the outcomes grantees were expected to achieve—particularly as it relates to moving residents out of shelters and into permanent housing.

The city had to tread carefully with nervous providers when it came to collaborating around data and performance. “There was a lot of intentional tone-setting and laying groundwork to build trust,” McCauley said. “We wanted to genuinely work with shelter providers to see what barriers they faced and what would help them move the needle to propel people to housing faster.” One finding from this work was that mental health and substance-abuse issues were not the top barriers clients faced, as stereotypes would suggest; instead, it was a lack of income and the wider lack of affordable housing.

To address those problems head-on, the city allocated $20 million in federal ARPA aid to rapid rehousing, rental assistance, and supportive services, an effort that began under the CARES Act of 2020. Another $71 million of federal funds will go toward housing the homeless, and $85 million from a local bond will fund shelter infrastructure, non-congregate housing and permanent supportive housing developments. To date, the city and its partners have successfully housed 1,300 residents and the average “time to house” has dropped from more than 100 days to about 60.

Chicago’s success with “results-based contracting” was one reason why the city recently achieved What Works Cities Certification as one of the best cities in the U.S. at using data to drive better results for residents. “We have been able to see that when you do have the resources, and barriers are removed to a certain extent, people are moving into housing,” McCauley said, “and moving into housing faster.”