Chief innovation officers reconnect as their movement grows

More than 90 chief innovation officers from around the world met at the Chief Innovators Studio in Amsterdam.

More than 90 chief innovation officers from around the world met in Amsterdam this month to share solutions and learn from each others’ experiences driving new ways of working in city halls.

It was the largest such gathering since Bloomberg Philanthropies began seeding the innovation movement in local governments a decade ago. And it was the first time this community of innovators has connected in person since the pandemic. That smoothed the way for a dynamic, global exchange of ideas that hasn’t been possible in years.

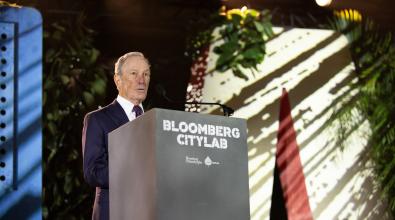

“It’s impossible to replace the chemistry that flows from direct personal interaction,” Michael R. Bloomberg, the founder of Bloomberg LP and Bloomberg Philanthropies and 108th Mayor of New York City, told the group. “You’re here in person, and we are going to do everything we can to help you be effective. Being a chief innovation officer is a lot of work. You’re responsible for driving change.”

A lot has happened since the last time the chief innovation officers gathered face-to-face in 2019. The pandemic showcased the value of using innovation tools like data, human-centered design, and collaboration to get COVID-testing, vaccines, food aid, and more to vulnerable residents. There are also many new faces among the innovators as newbies join more experienced colleagues in other cities who have been in the role since the beginning.

That is a sign of the innovation movement’s growing strength. “This is a movement that has elders, has established best practices, and has staying power,” James Anderson, who leads Government Innovation programs at Bloomberg Philanthropies, told the chiefs. “The offices you are leading are becoming fixtures in local governments. They’re surviving political transitions, and increasingly funded with public dollars.”

The public-sector innovation movement is also growing more diverse, said Amanda Daflos, who was the first chief innovation officer in the city of Los Angeles and now heads the new Bloomberg Center for Public Innovation at Johns Hopkins University. “There is more diversity of every kind in rooms like this one,” Daflos said. “That means there are more voices in the work we’re doing, which is critical to the success of the movement and the future of government.”

The gathering, called the Chief Innovators Studio, took place just ahead of the Bloomberg CityLab summit. About half of the participants were women, and the group overall hailed from two dozen countries. Among them were leaders of six new digital innovation teams funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies, who also joined together for the first time.

A big theme of the day was the power of inclusion in innovation. Dr. Victor Pineda, president of World Enabled, an advisory group supporting innovative approaches to inclusive urban development, outlined steps cities such as Amsterdam, Barcelona, and New York City are taking to engage persons with disabilities in co-designing public spaces and policies.

Pineda, who uses a wheelchair, asked innovators to infuse accessibility into local government’s DNA, including leadership, budgeting, procurement, human resources, and resident engagement. “You can’t rely on just one agency to drive inclusion,” Pineda said. “It has to be an all-of-government approach.”

Innovators shared their motivations for working in public service. One of them, Andrea Apolaro, who heads the Citizen Innovation Lab in Montevideo, Uruguay, traced her roots to wanting to save the world and take care of sick people as a child. “I have a passion for helping people, to solve their problems with creative solutions,” Apolaro said. Leading the innovation lab, “I work with people in my city to channel collaborative and experimental solutions.”

And innovators shared some of the cutting-edge work they’re leading that can be adapted by other cities. José Merino, who heads Mexico City’s Digital Agency for Public Innovation, described how his city has streamlined many services into a single app, leveraging a user-authentication tool that has reached a staggering 4.3 million residents. Tel Aviv’s Dana Schleifer described how her innovation team is engaging 18- to 35-year-olds to co-design strategies for making the city’s arts institutions more appealing to young people.

And Brian Smith of Minneapolis described how the i-team he leads used innovation processes to start diverting some calls for service away from a police response. Two new Behavioral Crisis Response teams now handle an average of 125 incidents a week related to mental health, meaning that residents in crisis are met by counselors rather than armed police officers. “This is a new first responder service in the city,” Smith said. “And it’s the first one developed by residents rather than one that government told residents, ‘this is what you get.’”

A number of the new chief innovation officers gathered are the second, third, or even fourth person to hold the position in their cities—another sign the role in local government is here to stay even if the people in them, naturally, move on.

Nicolas Diaz, the third chief innovation officer in Syracuse, N.Y., reflected on how the role there has grown and evolved. A big change is a shift from focusing innovation efforts on a single service to taking on bigger-picture projects. For example, the Syracuse team is now doing systems-level work on things like tracking performance of budget investments and reforming procurement systems. “We’re seeing that if we really want to commit to changing how things are working, we need to be in there for the long haul,” Diaz said.

Jayson D’Alessandro is the fourth innovation chief in Mobile, Ala. He said the role has changed over the years as new directors have brought their own “superpowers” into it. While previous directors were gifted at forging community connections, D’Alessandro said, his gift as a designer is “I can quickly see how things need to be adapted and show and tell that story.” His focus going forward is going to be making process improvements across multiple city services.

Process improvement is also a big focus in Denver, where Megan Williams became the third director of the city’s famous Peak Academy last year. Peak trains city employees in tactics for spotting and fixing waste in their everyday work, and works with agencies on more strategic ways of working. A dashboard on their website tracks the cumulative savings to taxpayers of innovations born out of Peak—$52 million and counting. “In the beginning, we had not built up that reputation of success,” Williams said. “Now, people can see the savings. We’ve got the track record. And because of the way we work with people and make people feel heard and seen and valued, they come back and want to work with us.”