Boosting mental health during a pandemic: 4 things mayors can do

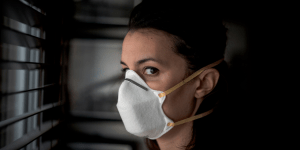

A month-plus into the Covid-19 crisis, the psychological strain of social isolation, health worries, economic distress, and grieving is showing up in communities across the U.S.

Feelings of depression, loneliness, and anxiety are through the roof. Parents say they’re yelling at their children more. Reports of domestic violence are up. Doctors are worried about a potential spike in suicide. Alcohol consumption is soaring, and a number of counties are reporting a new surge in drug overdoses. Health care workers are stressed and some show symptoms of trauma.

Dr. Kimberlyn Leary, a professor at Harvard Medical School/McLean Hospital and a clinical psychologist, recently spoke with mayors about how they can respond to these and other mental health concerns in their cities. And, as part of the learning and coaching sessions of the Coronavirus Local Response Initiative, she led them in a discussion about what they’re seeing in their cities — and what they can do about it.

This is a particularly challenging situation for mayors, Leary explained. Some of the very steps they need to do to protect the community — such as enforcing strict social distancing rules — are also exacerbating mental health problems. At the same time, mayors and their staffs are themselves coping with extraordinary stresses, both at work and home.

[Get the City Hall Coronavirus Daily Update. Subscribe here.]

Nevertheless, Leary said there are four things mayors are uniquely positioned to do as leaders in their communities to address these growing mental health concerns.

1. Use your bully pulpit. As mayors enforce physical distancing, they also can reinforce the need for social connection. They can remind residents to check in on friends and relatives, and they can speak directly to specific groups such as healthcare workers, teens at home, or people with disabilities. “You can acknowledge the economic challenges that so many people are facing, while also amplifying positive stories,” Leary said. “People need to hear both.”

2. Build up and promote available resources. While demand for mental health services is growing, services are available at the local, state, and national levels. There are crisis hotlines and texting services, peer-to-peer help groups, pastoral care services, and more. In addition, the availability of tele-mental health options are quickly growing. Mayors can build partnerships with nonprofits and other groups to further build up these services and promote their use, especially with vulnerable populations.

3. Mitigate stigma. By talking about these issues regularly, and using inclusive language — “we” and “us” — mayors can normalize the stress every resident is feeling and reduce the stigma that remains around seeking mental-health help. Mayors also can be mindful with their words, for example, by talking about “people who have Covid-19” rather than referring to “Covid-19 cases.” “To the extent you can,” Leary said, “encourage people to seek help” and convey that “seeking help is a sign of strength.”

4. Honor unspeakable losses. The scale of death and grieving is profound, and made worse by the hardship of being unable to mourn losses together in a time of social distancing. This is a time when mayors need to be the local “comforter-in-chief,” Leary said. “Your ability to speak honestly about those losses, and to help people come up with new rituals to honor those losses, is going to be critical.”