For this AIDS activist turned mayor, Covid-19 is all too familiar

When the Covid-19 outbreak began to be felt in the U.S. in February, Sean Strub had a sinking feeling; he’d seen this movie before.

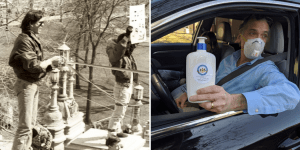

Strub, the mayor of tiny (pop. 1,000) Milford, Pa., experienced the HIV/AIDS epidemic as an activist, journalist, author, and HIV-positive person. So, when another potential epidemic began to surface, he didn’t want to see past mistakes repeated.

“We started mitigation earlier than many other places, certainly in Pennsylvania, with a shut-down recommendation on March 12,” Strub said. “In the HIV/AIDS epidemic, I’d witnessed first-hand the impact of government inaction and indifference and how that can translate into harmful public health outcomes. Now that I’m a public official, I was determined that would not be me.”

Strub is the founder of POZ magazine, a print and online journal for people living with and affected by HIV/AIDS, and the executive director of the Sero Project, an organization focused on ending criminalization, mass incarceration, racism, and social injustice for persons living with HIV/AIDS. He said he was determined to “err on the side of doing too much. I’d rather people be mad about that than not doing enough.”

In Milford, a small community in Pike County near the Pennsylvania/New York border, that’s meant a steady stream of communication to residents who lack the medical facilities of a larger community. As the pandemic has hit Milford — there have been at least 300 confirmed cases and eight deaths in Pike County — the measures Strub has taken include:

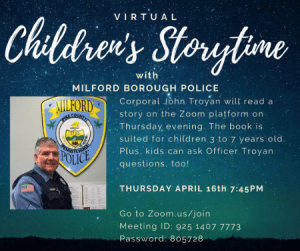

- Making the city’s Facebook page a daily lifeline filled with information and diversions that have included a story hour starring local police officials. Strub also has used a regular radio spot, a listserv, and newsletters to keep his constituents up to date.

- Providing regular video meetings of the borough public safety committee that included guidance from a local doctor, Doug Manion, who also is a well-known epidemiologist and HIV-AIDS clinician.

- Starting an online tracker for Covid-19 cases in the county as well as across Pennsylvania, a resource that is still updated daily by volunteers.

- Encouraging residents to shelter in place, but also to maintain relationships with each other. “We try to avoid the term social distancing; we prefer safe distancing or physical distancing, because it’s important for us to keep our social connections,” Strub said. He owns a boutique hotel and restaurant and has encouraged residents to patronize other local eateries for pick-up and delivery meals and offered vouchers for local restaurants to residents in need.

- Raising money through a Covid-19 relief fund at the Greater Pike Community Foundation. Strub said the fund had already raised $20,000 and made a $4,000 grant to a local church to help residents pay bills and buy diapers.

Clear communication and planning are crucial, Strub said, given that Pike County (pop. 55,000) has no hospital, urgent care facility, or county health department. There’s no daily newspaper headquartered in the county and a third of the homes are weekend or seasonal dwellings. “We have conditions that make it difficult to communicate. We don’t have visible public health leadership,” Strub said. Milford and the surrounding county have been hit hard by the outbreak. For weeks, Pike County had the second-highest concentration of cases per capita for Pennsylvania counties, but has now dropped to fourth or fifth.

Strub’s memoir, Body Counts: A Memoir of Politics, Sex, AIDS, and Survival, chronicles his witness of the HIV/AIDS pandemic, a period he said reminds him in some ways of the present moment. “Just the constant anxiety…in the epidemic there were years when it never escaped a person. Every day you were thinking about it.

“What is not familiar is the amount of attention, having governors and presidents on TV every day,” he said. “Physical distancing also makes it different. During the epidemic, we could hug our friends — even if others were afraid to.”

As he looks to the future, Strub fears another potential similarity between the two epidemics: the potential for criminalization and invasion of privacy for those who may have had Covid-19 or may be shown to lack immunity. The Sero Project has put out a public statement warning of Covid-19 criminalization. That’s an issue, he said, “we should be taking very, very seriously.”