4 things mayors can do to address COVID-19 racial disparities

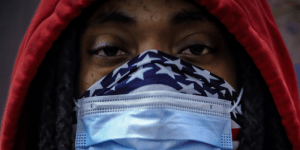

As alarming as the COVID-19 pandemic has already proven, data released this week — that the virus is infecting and killing a disproportionate number of African-Americans — is nonetheless shocking.

In Chicago, Mayor Lori Lightfoot announced that African-Americans, who make up 30 percent of the city’s population, account for 72 percent of the COVID-related deaths. Similar disparities are unfolding in other jurisdictions that are collecting data by race, including Milwaukee County, Wis., and Washington, D.C.; New York City announced yesterday that COVID-19 is killing black and Hispanic residents at roughly twice the rate of white residents.

Explanations for this disparity vary: from the greater prevalence of underlying conditions — including diabetes and lung cancer — among black Americans to the possibility that more African-Americans are exposed to the virus while working in essential jobs that can’t be done from home. While researchers explore these and other potential causes, mayors are moving quickly to tackle the problem. Lightfoot, for example, is setting up a Racial Equity Rapid Response team to step up targeted outreach and education efforts.

To discuss more about what mayors can do right now, we spoke with Augusta, Ga., Mayor Hardie Davis, Jr., who is president of the African American Mayors Association. Here are four things Davis said mayors can do right now to address racial disparities with COVID-19.

1. Get the data. Many cities are struggling to get accurate, local demographic information on caseloads from their state health departments, Davis said. In Augusta, for example, “we were provided with a pie chart that says 20 percent African-Americans, 14 percent white, and 64 percent unknown,” Davis said. “That’s completely unacceptable.”

Mayors need to push their state health departments and governors for disaggregated data around race, ethnicity, and gender, he said, adding that this can be done without violating privacy laws. “It’s a false argument to say they can’t provide this data…. We know that’s not true.”

2. Use the data to target resources. With the data in hand, mayors’ teams can look for patterns. “If we can get that data and localize it by ZIP codes, we can identify where there are hotspots and potential for hotspots,” Davis said. “And then we can mobilize testing and other resources. Increasing access to testing is a critical item that has to happen — especially in communities of color because of the disproportionate health disparities that have been there for generations.”

3. Step up outreach and communication. A lot of incorrect information has trickled down from the federal and state levels into communities, Davis said. “That’s led to misinformation in communities of color that African-Americans are not as susceptible to COVID-19 — and that’s absolutely not true,” he said. “We’ve got to go back now and do some reeducating that COVID-19 infects people of all races, ethnicities, and genders, and we’ve got to do an even better job of doing those public service announcements using the CDC guidelines, particularly as it relates to staying home and washing hands.”

4. Be a bold leader. “Foremost, mayors have to continue leading their cities in the manner in which you see happening all across the country, and raise this critical issue around race,” Mayor Davis said. “This is a very fluid situation, and mayors are having to lead in the moment.” That’s because, he added, “When it comes to COVID-19, the playbook doesn’t yet exist.”