4 secrets to successful citizen engagement

At a time when trust in national government has reached new lows around the world, cities are finding exciting ways to deepen their connections with citizens. They’re opening up to new forms of collaboration, tapping not just the energy of volunteerism but also the insights and talent that citizens can bring to bear on the most pressing urban challenges.

Last week, leaders from some of the world’s most innovative cities gathered in New York City to share their experiences. Most were among the 10 finalists for the first Engaged Cities Award offered by Cities of Service. The cities of Bologna, Italy, Santiago de Cali, Colombia, and Tulsa, Okla., brought home awards of $70,000 to expand and replicate their successful strategies. (You can read up on all ten of the finalists here.)

Here are several themes that emerged from a day of celebrating the value of public participation in local government.

Citizen capacity is an amazing force to tap into

Like many cities today, Tulsa has invested heavily in data collection and opening datasets to citizens. But staff have limited bandwidth to analyze all that data and harvest it for insights. Mayor G.T. Bynum turned to citizens to help, by creating a group called the Urban Data Pioneers. Volunteers join with city staff and data scientists to cull through data and then feed findings back to city hall to inform decision making.

Bynum said he was blown away by how much citizen interest there’s been in doing this kind of wonky data work. At an initial meeting, he expected 10 people to come; 60 showed up. Now, the group is up to 120, about one-third of whom are citizens working on their own time. Their findings are informing a range of city strategies, from fighting blight to prioritizing street repairs.

“Our greatest surprise is that there’s this capacity we had totally overlooked,” Bynum said. “There’s all these people with the abilities to help our city make game-changing decisions, and we were not aware of it.”

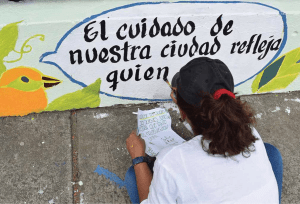

City leaders in Santiago de Cali came to a similar realization in a very different way. To combat gang violence and build trust between neighbors, they created local councils in 15 districts. The councils have launched more than 200 community initiatives, including fixing public parks, clearing debris, and organizing arts events and sports tournaments. In some cases, ex-gang members have joined the efforts.

“What surprised us is the capacity of Cali citizens to get up, continue, and succeed,” said Rocio Gutierrez Cely, the city’s Secretary of Peace and Civic Culture. “Our city was the biggest route for drugs, with 200,000 people affected by these drug wars. The capacity of citizens to get up and try to do something better is remarkable.”

Make it easy for citizens to help

Not long ago in Bologna, a group of women living near a public square got tired of seeing paint peeling from old benches.They approached city authorities, volunteered to paint the benches themselves — and then ran into a bureaucratic buzz saw. No fewer than five city departments needed to sign off on their offer, and the approval would take months.

City leaders recognized that it should be easier to say “yes,” and responded with a regulation clarifying how citizens can volunteer their time and talents improving public spaces. They also set up an “Office of Civic Imagination” to offer citizens everything from paintbrushes to technical assistance, and to experiment with new ways of co-designing projects with citizens.

“Trust starts from simple things,” said Deputy Mayor Matteo Lepore, noting that the city has signed 400 “pacts” with citizens to do different kinds of projects over six years. “From restoring benches to a school to a building, we’ve discovered we can find simple solutions involving people.”

Cultivate citizen leadership

Citizen activism is not automatic. Sometimes, concerned residents or business owners need a nudge to become more active leaders in their communities. And the active leaders sometimes burn out from balancing volunteer work with their busy lives. So it’s important for cities to nurture citizen leadership.

Helsinki does that very intentionally, said Muttaqi Khan, chairman of the city’s Young Muslims group. Not only does the local government fund his organization. It also engages them and other groups in policymaking, particularly around the question of improving services for immigrant youth. One result of that co-design process is a program called Make Some Noise, a leadership and public-speaking program that has trained 16 young immigrants to tell their stories. Khan is one of them.

“I gave a talk at my primary school,” Khan recalled, “and afterward, there were so many second-generation immigrant kids who came up to tell me where they’re from. And the smile on their faces — they’re used to seeing white Finnish people talking about things. That meant a lot to me. I can make a difference if I get a platform and know how to talk about my issues in an effective way.”

[Read: How Helsinki uses a board game to promote public participation]

Mexico City tried a very different approach at cultivating leadership when it turned to citizens for ideas for its new city constitution. Residents could propose petitions via the online platform Change.org. Those who had 10,000 supporters online got an audience with the working group drafting the constitution. Four residents who cracked 50,000 were able to personally pitch the idea to the mayor.

“They felt so much responsibility because of all the people who were backing them,” said Mexico City’s Gabriella Gómez-Mont, whose Laboratory for the City led the crowdsourcing effort. Gómez-Mont told the story of a 60-year old woman who, through the process, built a large following of people concerned about animal rights. That helped her and others make a successful case for a new animal hospital in the city. “She has about 50,000 followers, which is probably more than many congressmen,” she said, “and with the push of a button she can rally them.”

Engagement starts from the top

Gary, Ind., has a problem with overgrown grass on vacant lots. So every few weeks, Mayor Karen Freeman-Wilson goes out with a lawnmower and mows some of it. When curious neighbors come over to chat, they get the message: Take responsibility for keeping up the lots on your block. “I never have to ask,” Freeman-Wilson said. “They see me cutting, and they say, “Mayor, if you cut it, I’ll maintain it.’ We do it all over the city.”

Political leadership is essential to citizen engagement. Part of it is leading by example, as Freeman-Wilson does — being visible in neighborhoods, handing out her cell phone number and actually responding to calls, texts, and tweets. But it’s also about setting a tone for city employees, and communicating that engaging with residents is simply an expected part of the job.

Huntington, W.Va., Mayor Steve Williams had all of this in mind when he began taking his “mayors walks” through different neighborhoods. With the city facing an obesity crisis, Williams wanted to both demonstrate the value of physical activity while also finding out what’s on residents’ minds.

“Previous mayors would have open houses where people could come into the mayor’s office without appointments and talk about something,” he said. “And I thought, why not just take it to them? We can walk through the neighborhood and they can say, ‘See that dilapidated house? See that pothole? See that broken sidewalk’?” Williams has now led more than 50 of these walks and scheduled more for this summer.