Taking the pulse of public-sector innovation

As a new report identifies global trends in public-sector innovation, here’s where cities are leading the charge.

Where is public-sector innovation heading? A new report, “Embracing Innovation in Government,” provides some answers and identifies four global trends, including: 1) new forms of accountability for a new era in government; 2) new approaches to care; 3) new methods for preserving identities and strengthening equity; and 4) new ways of engaging citizens and residents.

But because this annual analysis, published by the OECD Observatory of Public Sector Innovation and the Mohammed Bin Rashid Centre for Government Innovation, takes a broad look at innovation at all levels of government, Bloomberg Cities has gleaned some of the report’s city government-specific details. Here’s what we found.

Public-sector innovation is more strategic and increasingly systems focused.

This year's report includes more innovations than ever—1,084 compared to 161 in the inaugural report in 2017—and those innovations show a new level of sophistication across the field, according to principal author and OECD Innovation Specialist Jamie Berryhill. “The nuance of the efforts we’re seeing is much greater, in a very positive way,” he says. “When we first started [in 2017], we’d see a lot of interesting stuff that wasn’t super directed or strategic; it was trying new technologies just to try new technologies, or putting in something new and different because they've seen something like that work elsewhere. Over time, these innovations have gotten much more strategic and systematic, so that they are really aligning things in new ways across levels of government instead of as these one-off kinds of interventions.”

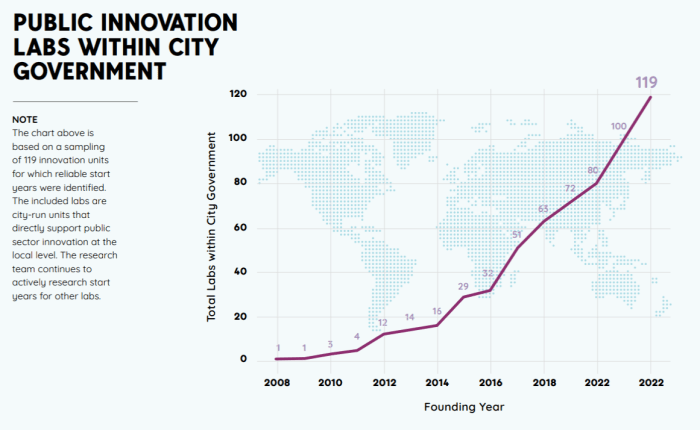

Berryhill also reports that there were more city innovations than ever submitted for this year’s report. This trend mirrors Bloomberg Philanthropies’ insight, reflected in this research from the Bloomberg Center for Public Innovation at Johns Hopkins University, that shows a global proliferation of city-funded and -focused innovation units—from one in 2008 to 119 by the end of 2022.

Digitalization is driving resident engagement and trust-building efforts.

As governments at every level turn to resident engagement as a means to build trust, local governments are doing much of the legwork. Indeed, as the OECD report identifies “new ways of engaging residents” as one of the emerging trends in public-sector innovation, it also spotlights that “the majority of the implemented initiatives exist at the local level.” Earlier OECD research also shows that local leaders are more trusted than their peers at other levels of government. But that doesn’t mean there isn’t a lot of room for improvement: Slightly fewer than half of respondents to the OECD survey said they trust local government.

“What we’re seeing in this report is the evolution of public engagement and stakeholder engagement,” Berryhill says. “There’s more maturity and more recognition that the best sense for what residents need is not completely known by a bunch of smart people from government in a room trying to figure things out.”

With those lessons in mind, cities are scaling their resident engagement approaches by taking advantage of a new opportunity: digitalization. From enabling community members to participate in proposing their own landscape architecture solutions using augmented reality in Tallinn to crowdsourcing data on damaged streets from bicyclists in Helsinki, governments have made digital tools a centerpiece of their approach.

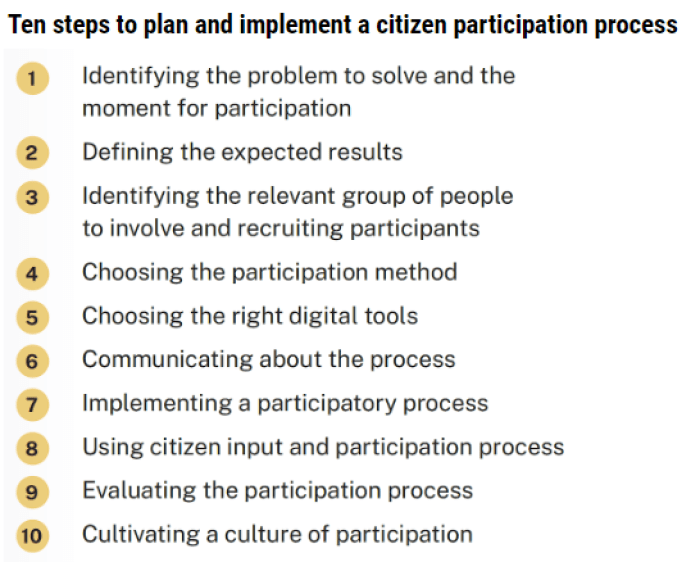

This report also highlights a 10-step citizen participation model—with digital tools at its center—to help city leaders take action.

How cities can flex their innovation muscle for impact.

In describing one of its four key trends, “new approaches to care,” the report also highlights approaches cities are employing in this space that could help them in the face of other challenges.

One of them is in the way city leaders are rethinking service delivery. “Rather than requiring citizens and residents to go to different organizations and offices based on the functional structures of government, government absorbs this burden and provides holistic services that meet people where they are.” That’s a core characteristic of Bogotá’s CARE Blocks program, which was both an innovation examined by the OECD and a winner of Bloomberg Philanthropies’ 2022 Global Mayors Challenge. The program not only centralizes support services for the city’s 1.3 million women who work as unpaid caregivers, it also includes mobile units that deliver service to those women’s homes and personnel who can relieve them from their home-care burdens while they’re taking advantage of those services.

[Read more about Bogotá’s pioneering approach to public health.]

The report also identifies a secondary trend around “public administration transformation,” where governments are rethinking nuts-and-bolts operations, like procurement, to drive change. This is reflected in a number of innovations highlighted by the OECD, including the Plymouth Alliance Contract, an effort in Plymouth, U.K., to consolidate 25 contracts—spanning supports for people that include substance-related issues and homelessness—into one. This cross-cutting work is emblematic of how local governments can put larger, systems-focused approaches to work not just on service delivery, but also on internal operations.

What’s next for public-sector innovators?

One of the biggest benefits of a report like this is to “spread ideas, have other people test them and adapt them to their own cultures and context, and then see what works,” Berryhill says. Bloomberg Philanthropies provides one model for this: Taking winning ideas from its Mayors Challenge program and supporting cities around the world in adapting and implementing them. This is driving the adoption of proven ideas such as Stockholm’s biochar program—which enables the reuse of plant waste from parks and homes to help combat climate change.

As local governments continue to grow their innovation capabilities, there’s also an opportunity for practitioners to compare those efforts to the hundreds of case studies that have already been cataloged by OECD. “That’s the level of exchange we’d like to see more of,” he adds. “Not every city needs to reinvent the wheel.”