Putting ex-offenders back in the driver’s seat

One night during dinner a few weeks ago, Ryan Smith’s phone began buzzing with text messages and emails. That’s when he knew a project he helped design for the city of Durham, N.C., was working better than he’d ever imagined.

The flood of messages was coming from residents who’d had their driver’s licenses revoked — many of them because they’d once been in prison. They were reaching out to Smith, city hall’s innovation team (i-team) project manager, to get their license back so they could drive legally again.

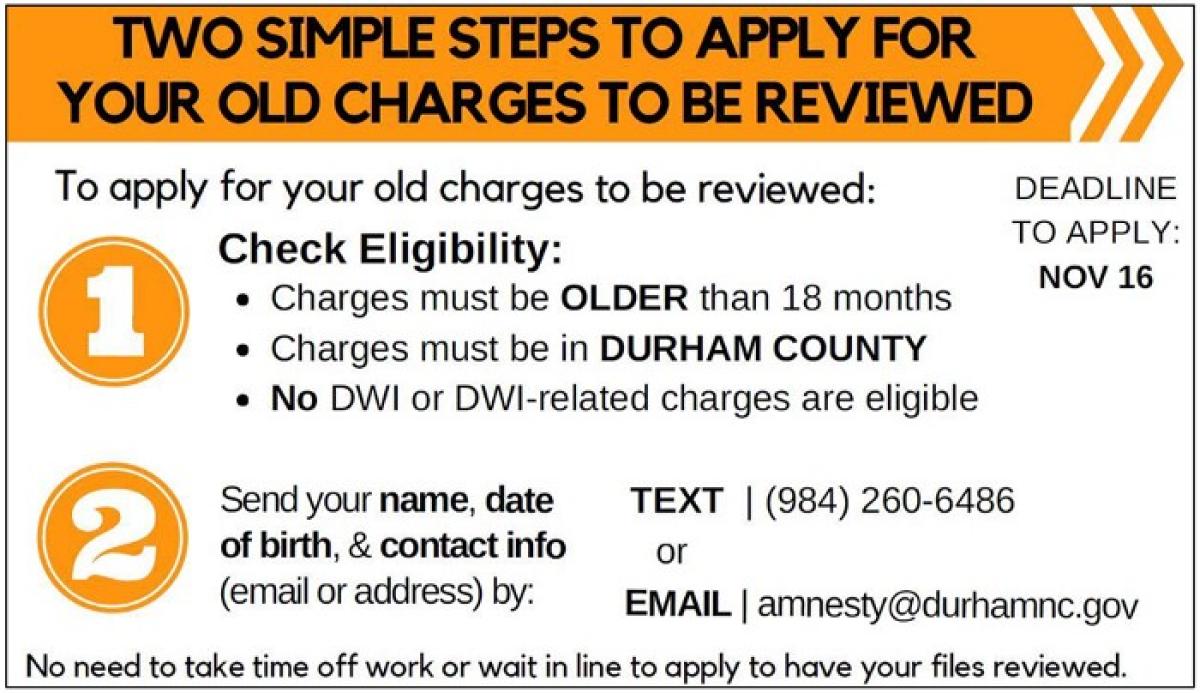

Reclaiming a driver’s license after it’s been revoked or suspended can be a frustratingly difficult and expensive thing to do, especially for people getting their lives back on track after prison. So as part of an amnesty effort, Smith and his colleagues in the city’s i-team devised a workaround: “Just send us your name and date of birth,” they told residents looking to get their licenses back. “We’ll work with the District Attorney’s office to do the rest.”

Nobody expected an outpouring of response, which was all directed to Smith’s email address and phone number when the initiative first went public. “We were caught off guard. In just the first two or three days, nearly 1,000 people sent their information in,” Smith said. “I remember sitting at the dinner table and eating with one hand and responding to text messages with the other.”

This simple but innovative solution is part of the Durham i-team’s larger mission to make it easier for people with criminal records to get jobs or go to school, a critical factor in reducing recidivism and lowering incarceration costs for taxpayers.

Yet the justice system often tangles ex-offenders in red tape — and, worst yet, places the burden of cutting through that tape on the ex-offenders themselves. Durham’s i-team flipped that narrative around. With the driver’s license initiative, they put the burden of managing the bureaucracy on their own shoulders — and then worked with partners in the District Attorney’s office and nonprofit sector to find creative ways to reduce it.

“The reality is that when you get out of prison and you have outstanding charges, even from traffic court, the last thing you want to do is go back to the courthouse to figure out how to deal with them,” Smith said. “We have to recognize where people are coming from.”

Driving data

The focus on driver’s licenses grew out of conversations the i-team had with ex-offenders and others Durham officials refer to as “justice-involved” individuals. They also spoke with community partners, including the Durham District Attorney’s Office and nonprofits such as the North Carolina Justice Center and the Southern Coalition for Social Justice, to understand the challenges that formerly incarcerated residents face when trying to access economic opportunities. Over and over again, they heard about the obstacles to getting a driver’s license.

In Durham, as in many cities, everyday tasks and employment can be almost impossible without a driver’s license. Without a license, one’s options are often limited to long bus rides, hitching rides with family or friends, or driving illegally without a license — an offense that can lead right back to jail.

Digging into the numbers, the i-team confirmed the depths of this challenge: Across Durham County 46,000 residents currently have their licenses suspended. Driving with a revoked license is one of the most common offenses faced by people in the county jail.

In North Carolina, driver’s licenses are automatically suspended for failure to pay a traffic fine, and low-income residents who choose to pay a utility bill over a speeding ticket can find themselves without a license or a way to get to work.

Durham i-team members were meeting with the District Attorney’s office in November to discuss barriers faced by formerly incarcerated residents when the DA’s office suggested partnering to host an amnesty initiative. The idea was to give people a chance to have outstanding charges and fines against them waived so they could get their licenses back.

The i-team leapt at the offer. And, as they got to work, Smith and his colleagues learned they’d have to move fast — as a state law taking effect in December prevented such amnesty. This left them with only 10 days to both come up with a plan and let the public know about it.

“If we had an opportunity to plan longer we would have,” Smith said, “but the changes in state law compelled to us to move as fast as we could.”

‘People couldn’t believe it’

This wasn’t the first time Durham had held an amnesty event related to reclaiming revoked driver’s licenses. But previous ones resulted in limited success.

In part, that was because it was difficult for people to determine whether they even qualified — and then, if they did qualify, they were required to show up at the courthouse in person to have their records reviewed.

The in-person requirement dissuaded many people from participating: They couldn’t drive, after all. Others wanted nothing to do with the courthouse after having negative experiences with the judicial system, or simply couldn’t take time off work. Moreover, people could only apply on a particular day. Typically, only 15 or 20 people would apply for amnesty.

The i-team, working closely with the DA’s office, took several steps to overcome these barriers. First, they ensured residents could have their records reviewed without showing up at court. All they needed to do to initiate a review was to send a text or email requesting it — and then the DA’s office took on the responsibility of determining who qualified.

Next, to get the word out, they worked closely with the city’s outreach director, who canvassed neighborhoods and community gathering places such as barber shops. Nonprofit partners also helped spread the news and encourage people to apply. For those accustomed to difficult interactions with the justice system, the process was shockingly easy. “People couldn’t believe it,” said Josh Edwards, director of Durham’s i-team.

Overwhelming response

The results — as Smith began to suspect when his phone began buzzing — were staggering. The i-team hoped they might get a few hundred people to apply for amnesty. Instead, more than 2,200 people asked for their records to be reviewed.

Edwards credits the overwhelming response in part to the simpler process and in part to the outreach by partners. “There’s a real power to partnerships,” he said. “These residents might not trust me, but they will trust our partners, and it’s something that everyone agreed was legitimate.”

The deluge of applicants also meant that both the i-team and the District Attorney’s office had a lot more work to do than they’d anticipated. “We didn’t realize how much of a crush it would be, but we got through it,” Smith said. “Our efforts make me proud. For so long, we have been shifting the burden onto people who are incarcerated, including fines and fees, and this was a small way of shifting the burden back to government. It took applicants two minutes of their time, and it took us weeks.”

By late December, the District Attorney’s office had gone through all applications and reported that more than 450 people would have charges dropped. The initiative identified more than $260,000 in associated fines and fees that could potentially be waived. Individuals still need to pay a restoration fee to the state Department of Motor Vehicles to get their license back.

Assistant District Attorney Josephine Davis hopes what Durham did can be the start of a larger movement toward helping ex-offenders get their rights back. Reviewing thousands of cases was a lot of work, but it was worth it, she said. “I know these dismissals are changing people’s lives for the better.”

Durham’s i-team was developed in partnership with Bloomberg Philanthropies. Now working in more than 20 cities across four countries, the Innovation Teams Program helps cities solve problems in new ways to deliver better results for residents.