Garbage in, insights out: What every city can learn from Durham’s composting prototype

Tenita Poole had never separated her kitchen food waste for composting before. But when the innovation team in Durham, N.C., where she lives, approached her about trying it out for two weeks as part of a prototype, she was eager to give composting a try.

Poole’s family of nine does a lot of cooking with fresh greens, and there’s always a lot of table scraps that go into the trash. “I thought composting would be a wonderful idea,” she said. “I hate to waste food, and composting is really good for not wasting food.”

The children picked the practice up quickly, Poole said, scraping their plates into bags that filled quickly with bits of green beans and corn cobs, along with other compostable items like tissues and cardboard toilet paper rolls. Everyone in the family enjoyed it, Poole said, although the odor of old food in the house became a problem. “My only downside is the smell,” she said. “I had to put it out on the porch.”

Poole’s family is one of eight households that participated in the Durham i-team’s prototype this summer. Their feedback will be critical as the city builds a service it’s never offered before: curbside compost pickup. When all is said and done, the city hopes to divert as much as a third of its waste away from the landfill and then use it to produce a nutrient-rich soil amendment that local farmers, landscapers, and backyard gardeners can use to grow more food.

Developing a service like this from scratch is a pretty complex endeavor, requiring cooperation from residents, waste collectors, and others. That’s why the Solid Waste Management Department teamed up with the i-team, City Hall’s in-house group of innovation consultants. Funded through a grant from Bloomberg Philanthropies, the i-team is known for using collaborative strategies like prototyping to co-create policies and programs with the very people intended to use them. While Durham’s composting program still has a way to go before it launches, there’s a lot that cities everywhere can learn from the city’s use of these human-centered design techniques.

The effort, a partnership with the Duke University Center for Advanced Hindsight, started with interviewing Durham residents in their homes. Some of those interviewed already compost food waste in their backyards or through a private service, while others have never done it before. Either way, said Shannon Delaney, an i-team design strategist spearheading the compost work, the point was for city leaders to learn how residents deal with their food now — before they build out a whole new set of expectations.

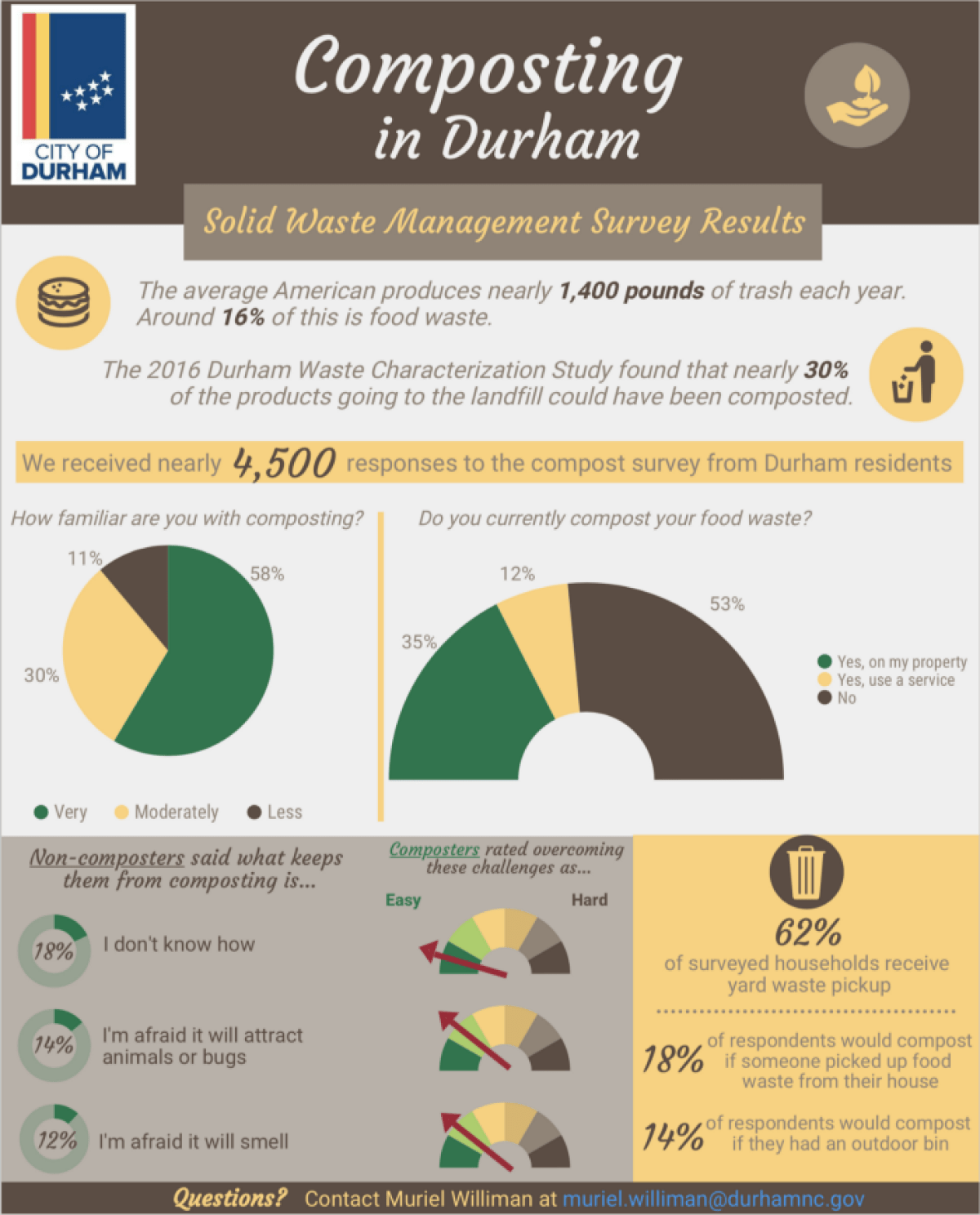

Next came a survey circulated through social media and neighborhood listservs. Nearly 4,500 residents responded, yielding a trove of data about public perceptions and knowledge of composting. The survey not only confirmed an interest among residents in launching a municipal composting service but also began to build a constituency and support network for getting it started.

“We hit a nerve,” said Muriel Williman, Solid Waste’s point person on the composting project. “A good number of people who are not currently composting are interested in learning — and those who already compost are interested in teaching others how to do it. Tapping into that wellspring of interest, desire, and knowledge — all this incredible social capital — is what’s going to make this program fly.”

[Read our explainer on prototyping]

Before they could do that, however, Williman and Delaney needed to see for themselves how Durham residents would respond to separating food waste in their kitchens. So they ran a two-week prototype with just eight households. Unlike a pilot — which would roll out a more complete version of a program — the prototype was intended solely as an experiment to gain feedback and learn from residents. The idea was to tinker in a low-stakes way before investing time and money in building out a more fully functional composting service.

To get started, the i-team reached out to some people who had taken the survey and others who had not, making sure to engage residents who reflect Durham’s racial and ethnic diversity. Every participant was given bags and buckets to put food waste in, along with a guide laying out what other items, like napkins or popsicle sticks, can go in the compost. The i-team used the messaging service WhatsApp to connect with everybody over the two weeks, both to answer any questions and to encourage them to keep photo diaries of their experiences.

Tenita Poole’s family demonstrated one challenge: volume. With so many people under one roof, they quickly filled up a plastic tote bag, which was soon too heavy for Poole to carry. The i-team expected to pick up everyone’s food waste once a week during the prototype, but they had to come to the Pooles’ house more often. The family also gave up gave up on composting meat scraps. Those would get really smelly if they weren’t stored in the freezer, and Poole didn’t have the space for that.

These kinds of learnings emerged frequently during the prototyping process. While there were complaints about odor and bugs, people generally were more willing to put up with more inconvenience than Delaney expected. Prototyping also exposed issues with contamination, especially from plastic infiltrating the compostable waste. Many people forgot to remove the little stickers that often come on store-bought produce. One person tried to compost loads of meat still wrapped in plastic packaging. These learnings will inform future tests, and ultimately, decisions about the service design.

“I had a theoretical understanding of what the barriers would be,” Williman said, “but seeing it and touching it and talking to people made the issues very human.”

[Read our explainer on human-centered design]

Another group Durham would like to prototype with is the waste collectors. In particular, the workers who currently collect yard waste are likely to gain responsibility for picking up compostable waste as well. Williman and Delaney recognize that these frontline staff know better than anyone what issues may arise. A few weeks ago, they hosted a conversation with a dozen waste collectors to begin tapping into their knowledge — and they hope to work with them this fall to prototype how compost collection could work.

“Collectors are one of the most valuable voices to have in the room,” Delaney said. Williman agreed: “They’re the gatekeeper between what comes out of people’s houses and into the composting facility. They have to be on board, so making them part of the process is key.”

Durham’s composting plans still have a way to go yet. The biggest unresolved question is where all the food waste will go for processing into consumer-grade compost — that’s a siting matter wrapped up in a host of environmental and regulatory considerations. But when it’s time to launch, Williman said, she feels confident that the i-team’s human-centered approach to engagement will help make it as smooth as can be.

“Nothing happens in their process without a thoughtful gathering of information and inputs and collaborative decision-making,” she said. “I appreciate the level of energy they bring, just this freshness in making social change that matters to our community.”