Explainer: What is a ‘randomized control trial’ and why are a growing number of local governments using them?

Thanks to the race for COVID-19 vaccines, the results of “randomized control trials” are now dinner-table conversation around the world—even for people who aren’t scientists or data geeks.

But the term has also been popping up more and more in city halls recently, and for a very different reason: Randomized control trials are increasingly seen as a critical innovation tool, one that can help city leaders experiment safely and build programs based on evidence that they work.

In our latest explainer, Bloomberg Cities breaks down the basics of what randomized control trials are all about in the local government context, and why city leaders these days are making more use of them.

What is a randomized control trial?

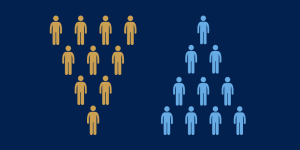

A randomized control trial is a scientific tool city leaders can use to learn whether a new policy, program, messaging, or some other change is working as intended. It’s not the only evaluation method available to do that, but it’s one of the most rigorous. The idea is to create statistically similar groups—including at least one that experiences the intervention, and another that does not—and then compare the results of each.

For example, Washington, D.C., is running one such test now in the city’s 911 call center. To cut down on unnecessary ambulance trips and E.R. visits, city leaders are experimenting with having nurses triage medical calls where patients report mild symptoms. If their assessment finds an ambulance is needed, they’ll call one. Otherwise, the nurses connect the callers to primary care or urgent-care clinics. To test the outcomes, some of these callers have been randomly assigned to the nurses, while others were randomly assigned to be handled as usual by 911 dispatchers.

While the final results are not yet in, Sam Quinney, who heads the city’s Lab @ DC science team, says the rigorous approach will give city leaders an evidence base to build future decisions on. “When we talk about ‘what works’ for people,” Quinney said, a randomized control trial “is the best way science has found to determine that.”

[Read: How Washington, D.C. brings science into local government]

Why are cities using them?

Randomized control trials are nothing new, of course—according to University of Exeter Professor Julian C. Jamison, their use in medicine dates back to at least 1835, and their use in social sciences began picking up in the 1920s.

What is new, at least in city halls, is thinking of them as an innovation tool that can be deployed rapidly—not just to evaluate existing programs but to build new programs iteratively from the ground-up. Bloomberg Philanthropies accelerated that shift through its What Works Cities program, which has enabled dozens of cities to work with experts at the Behavioral Insights Team on running these trials.

“It’s very aligned with the innovation mindset,” said Emily Cardon, a principal advisor at the Behavioral Insights Team. “When you don’t know everything in advance, randomized control trials give you a way to roll things out and improve them over time.”

Another reason city leaders are using this tool is they’re recognizing that even thoughtfully designed programs with good intentions sometimes fail. Trials can identify that early, flagging programs in need of reform or perhaps elimination. “Sometimes programs that intuitively make sense from a theoretical perspective actually backfire,” Cardon said. “We all have intuitions that some things will work or not, and often, the world is much more complicated than that.”

What kinds of city programs are they useful in evaluating?

For cities that are new to randomized control trials, a good place to start is with letters, bills, and other public communications. If the goal is to get residents to pay a parking ticket or renew a license, it’s not hard to design and send out two or more versions and see which one produces the best results. Some email and website platforms make it especially easy to run simple “A/B tests” on things like which email subject lines or headlines readers click on most.

In Portland, Ore., city leaders used a trial to see if redesigning a letter sent to businesses who are behind on their paying their license tax would boost compliance. (It didn’t.) A later test early in the pandemic produced a more positive result. Portland teamed up with the Behavioral Insights Team to test eight versions of a poster aimed at encouraging social distancing in grocery stores. The version found to be most memorable and convincing to people is the one the city went on to share and promote.

Once cities have built some muscle around this work, they can move into more challenging areas. For example, the Lab @ DC has used randomized control trials to test whether police-officer body-worn cameras affected police-community interactions (they didn’t). Current Lab projects include studying whether free and discounted transit fares improve wellbeing for residents with low incomes, and whether small but flexible housing subsidies can help some families avoid homelessness. According to Quinney, practically every step city leaders take to try something new or improve upon the status quo is an opportunity to evaluate it with a randomized control trial.

[Get the latest innovation news from Bloomberg Cities! Subscribe to SPARK.]

What’s involved in doing one?

While the details of setting up a randomized control trial get complicated pretty fast, Cardon said there are four main ingredients needed for cities to run one.

- First, they need to have a way to split groups randomly. Say you’re testing out whether a newly designed tax bill can get people to pay on time. One group of taxpayers would get the old bill, and at least one other group would get a new one.

- Second, cities need to have data to measure the outcome—the on-time payment rate in this case.

- Third, they need to be able to track that data back to individuals within the different groups, in order to be able to make comparisons.

- Finally, cities need large numbers in each group in order to yield results that are statistically meaningful. While there aren’t any hard rules here, Cardon said, “it’s best if you can aim for thousands.” If you were evaluating a small social program that serves just 50 people, she said, you’d be better off using a more qualitative approach to evaluation.

What challenges do cities face?

Where cities often struggle in this work is with their data systems, Cardon said—you need to have solid data on the thing you’re measuring right from the start. What’s more, while the benefits of building new programs based on evidence are clear, taking the time to run randomized control trials along the way can slow city leaders down. “The costs are all frontloaded,” Cardon said, “and the benefits are all at the back end.”

Lindsey Maser, who’s coordinated a number of trials in Portland, adds that city leaders need to be prepared for the possibility of “null” results. In other words, you may run a trial only to learn that a hopeful programmatic change made zero difference. “Honestly, it’s pretty hard,” she said. Still, Maser stresses that even a disappointing result pays real dividends. “If we’re not testing it, we can assume a program is working and step back and keep funding it—when we could have reallocated that money and staff time to something else that works, or at least something else that we can try and see if it works.”

What skills do cities need on hand to do this work?

A growing number of cities have dedicated innovation, performance, or data-science teams to run randomized control trials as part of broader efforts to drive a culture of innovation and data-driven decision making in local government. To really advance in this area, Quinney recommends that cities have some staff in-house who know how to set up randomized evaluations and interpret the results. Outside help can also come from universities, consulting firms, and contractors.

Just as important as the technical skills is securing buy-in for this approach up and down the organizational chart. At the top, it’s critical that mayors and city managers see the value in using evidence, and model data-driven decision making for the whole organization. At the same time, running any randomized control trial requires cooperation of the frontline staff who manage and administer whatever program is being changed, measured, and evaluated.

“From the top to the bottom,” Cardon said, “you need people bought in, seeing the value, and willing to put some effort behind it.”

Read more explainers from Bloomberg Cities: