How Washington, D.C., brings science into local government

If you associate Washington, D.C., with political dysfunction and government breakdown, you should think again. At the local level, at least, the city has become a hotbed of innovative thinking and evidence-based problem solving.

One of the best examples of this progress is The Lab @ DC, a City Hall-based team of data scientists, social scientists, and operations analysts who are applying science to the work of delivering better results for D.C. residents.

Since its 2017 launch, the Lab has released a groundbreaking study that found body-worn cameras have no detectable effect on policing activity, developed a statistical model to help the Rodent Control team locate rats, and engaged D.C. residents in events, called “Form-a-Palooza,” designed to make dozens of city forms more user friendly. The Lab’s rigorous work is part of why Washington, D.C. has earned a gold-level certification from What Works Cities, a sign that it’s one of the best cities in the country at using data for good governance.

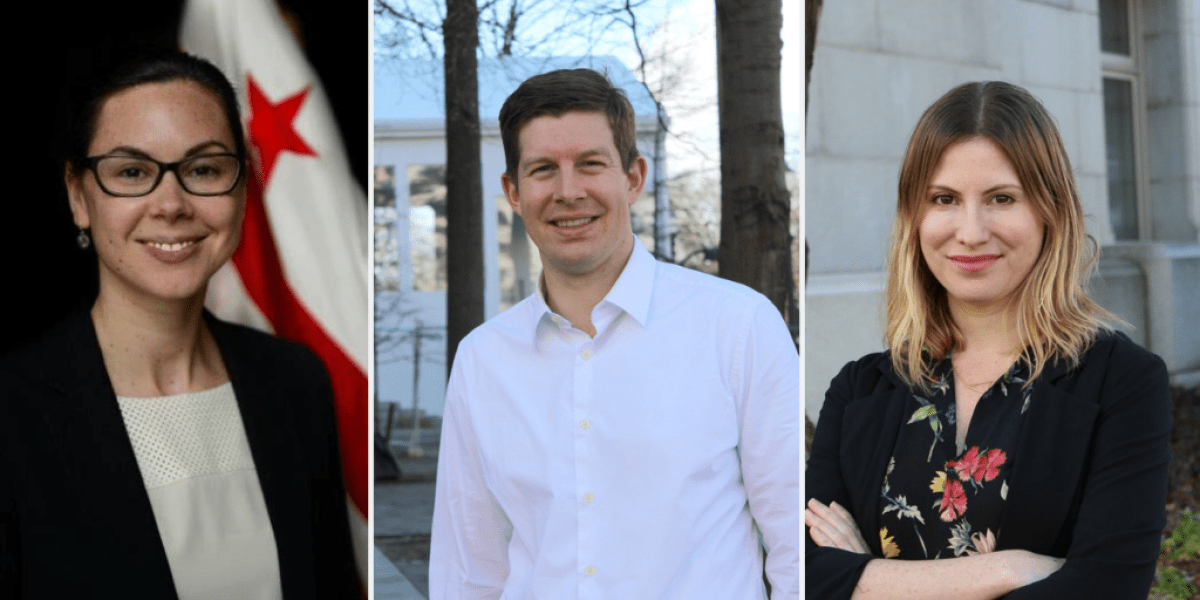

As urban leaders from around the world prepare to gather in D.C. for next week’s CityLab conference, Bloomberg Cities caught up with some of the people behind this experiment to learn more about how they work and what other cities can learn from it. We spoke with Sam Quinney, The Lab @ DC’s first hire and now its director; Jenny Reed, who oversees The Lab’s work as Director of the Office of Budget and Performance Management; and Chrysanthi Hatzimasoura, a senior social scientist with The Lab and research professor at The George Washington University.

[Get the latest innovation news from Bloomberg Cities! Subscribe to SPARK.]

How, in a nutshell, do you describe The Lab @ DC?

Sam Quinney: We’re a team that allows us to do more of what works for Washington, and we use insights and methods from science to do that.

How does The Lab choose its work?

Quinney: Some of our projects come directly from Mayor Muriel Bowser and City Administrator Rashad Young. They set the priorities and set the environment. They know through the democratic process what the priorities are for District residents, and they create the climate for agencies to really care about evidence and care about using data to make good decisions and hopefully improve outcomes for residents.

The work usually comes from the people leading city agencies, who say: “I’m doing this new thing” or “I’m addressing this new challenge.” We then engage in an exploratory conversation to see if we, as The Lab @ DC, can add value — if our skillsets can lead to a better outcome for residents.

Jenny Reed: From a budget perspective, we’re encouraging our agencies to use data and evidence more when they’re making decisions about resources. Not that they weren’t doing that before, but it wasn’t as intentional. So we created a process where, if agencies want to start or expand a program, they have to provide us with a variety of information, including data or evidence that shows how it will meet a particular objective.

Then, based on what agencies submit, The Lab looks at the academic research out there and validates it. We use that to have a conversation with the agencies. It doesn’t necessarily mean that if your program doesn’t have a huge number of randomized control trials to support it that we’ll say no, but it does mean we have an opportunity to say: “How will we collect data and evidence to measure performance of this program?” And, “Is this something where we should embed The Lab from the beginning to do an evaluation?”

Talk about the methods you use.

Quinney: The largest part of our portfolio is randomized control trials. That’s the best way to determine if something will work for D.C. residents. When we are administering a program—or even just sending an email or letter—we have one group that gets the program, service, or email and another that doesn’t. That way we can isolate the effect of the work.

Second is resident-centered design, where we’re thinking through residents’ interactions with government. It could be forms or websites or letters or applications for services, and asking: “What’s going to be the best experience for the user?” Our largest work has been on form redesign, through Form-a-Palooza. We’ve now taken more than 30 D.C. forms, which affect hundreds of thousands of residents, and made them cleaner and easier to understand.

[Read: How ‘Form-a-Palooza is helping Washington, D.C. simplify its forms]

It’s also a process of talking to the user. We redid the public schools enrollment packet this past year, and in order to test it, we had team members go out to schools at pickup and dropoff time to say to parents: “Let’s fill out this section together, what do you think of this part?” Or, “You paused here—does that mean the form confused you? Could we do something better?”

Next is administrative data analysis. If we can’t do a randomized control trial, we can still look at data to get our best understanding of whether a program works, or why a problem exists.

And finally, predictive modeling builds on that. We can connect data to predict, say, whether a block is likely to have a lot of rodents, or to target housing inspections to houses that are most likely to have a serious violation.

What’s the opportunity in this work for someone with an academic background?

Chrysanthi Hatzimasoura: It’s been a great challenge to be thoughtfully embedding the scientific method in day-to-day government operations. We’re not here to do a few studies and run away. It brings to the surface things you wouldn’t run into if you were an academic solely based at the university. You move from the armchair thinking world to a world where you’re engaging with the community itself.

What’s an example of that for you?

Hatzimasoura: We’re leading an evaluation of the 911 Nurse Triage program. [The program diverts people who call 911 with non-emergency medical issues to a nurse rather than immediately sending an ambulance.] We wanted to do a rigorous study of whether the program was having the effects that we hope for on ambulance use, on repeat use of 911, on actual health outcomes.

[Read: Behavioral science is quietly revolutionizing city governments]

In order to do that, we need a control group and a treatment group — but we’re also working in the 911 call center, where we have call operators who need to pick up the phone, be efficient, be on autopilot. We can’t have them pause and say: “Hang on a minute, let me check if you’re in the control or treatment group.” We had to work very closely with the staff to integrate the scientific method seamlessly into some very sensitive government operations. By doing that, we build trust with the agencies so they’ll want to continue to work with us and continue to concretely have the scientific method in their day-to-day operations.

How can local government recruit more scientists to do this kind of work?

Quinney: Those in government might assume that people based at academic institutions don’t care about getting into these details of how to make things work in the real world. In fact, we find there are so many people who want to come in and do public service — they just haven’t had the avenues to do it. Based on the number of people who want to come work with us at The Lab, I’m sure other cities have people in universities who have a similar public service motivation for their work.

The Lab breaks projects down into a six-part cycle: Listen, design, do something, test, decide, repeat. What happens at each of those, and why is this cycle important?

Quinney: To us, listen means that we’re working on priorities that matter to District residents.

Then when we design, we’re using the best available knowledge. So we’re learning from other jurisdictions, talking to the people who are affected by a program or administer a program, and designing based on rigorous evidence and data analysis.

Do something means that, rather than being evaluators off to the side, we want to be hand-in-hand with the implementation as it gets done. So that might mean assisting agencies with things as rudimentary as sealing envelopes or doing intake for a program that’s just getting started up.

Test gets at the methods we talked about earlier — once we’ve designed something as best as we can, it’s finding out: Did it have the effect we wanted?

Based on that, we decide — or, often, we’re informing a decision for different policy makers throughout the government.

And repeat means we keep doing it. No one project is going to solve, say, homelessness or economic instability. The way that science and evidence will move the needle is if we’re continuously going through cycles of this work. So when we find something that works, we need to be there to help implement it, and keep repeating what we’re doing over and over again.

How is this work influencing how the District budgets and spends money?

Reed: A good example is when the D.C. Public Schools came to us last year with data showing that an existing program — to add more days to the school year — wasn’t showing the results they’d hoped for. They wanted to shift their investment to another program — one that gave laptops or tablets to students — that had showed promise in the research and academic literature in improving student achievement.

The Lab looked at both evidence bases, and helped confirm two things: First, the research around extending the school year is mixed and, second, that the technology option has been shown to improve academic performance, provided the devices come with rigorous training and support for teachers and students.

It was a big programmatic shift, and we were able to have a conversation with them, supported by data and evidence, that this seemed like the best approach. So we proposed that, and council approved it.

How do you make sure The Lab’s work isn’t just some cool stuff happening on the side, but actually creating culture change more broadly?

Quinney: When we started designing The Lab, we were very conscious of not making it seem like this shiny thing or a flash in the pan. The goal from the beginning was to make this a part of government because we think it’s a core government function to do what we do, not something that’s a nice-to-have.

[Read: How to make innovation capacity stick for the long haul]

At least in D.C., we’ve found there’s a ton of appetite for this work, and it’s growing. The majority of our projects now are coming from people that we’ve either worked with in the past or they’ve heard about us from other people in their agency. They’re saying: “I have something I think The Lab can help with,” which is a really great signal of building this culture.

And how is it permeating into agencies?

Quinney: The Metropolitan Police Department now has a team that very closely mirrors The Lab within the chief’s office. They have two data scientists, someone who does process management and change management, and a social scientist coordinating the efforts. We’re seeing similar things at the Child and Family Services Agency and the Department of Human Services. Positions are precious things in government, so we think that’s a good indicator of the spread of the culture. And we’ve been kind of like a talent recruitment agency for departments. We’ve had to develop new position descriptions for government, like social scientist, data scientist, and operations analyst, and we’ve shared those with agencies along with our tools for assessing talent.

We think the long-term growth will be in these slightly smaller laboratories at agencies. There are so many decisions that need to be made across local government — we could never do anything close to all of it with a central team. So that’s the real growth strategy of The Lab — to see more people in agencies doing this work and having the central team here to coordinate those activities, provide resources, and a general framework for how we approach things with the highest level of scientific rigor, transparency, and good governance. But a lot of the project work for an agency will happen with agency employees.

What’s the biggest lesson other cities could learn from the work you’re doing here?

Reed: Having the buy-in and support from leadership is critical. Mayor Bowser and City Administrator Young have been champions. They ask agencies about data and evidence: “How do you know program x, y, or z will work?” That matters, because the message moves throughout the organization and builds support when we ask agencies for this information. If we were the only ones asking, it wouldn’t be as effective.

Hatzimasoura: Just the collegial culture we have within The Lab. This team is managed in a way where we all know what’s going on, what everyone is up to on a daily basis. We don’t use email internally at The Lab — we use a project management platform that’s very interactive and we’re all very active on it. We are managed very efficiently at the micro level without being micromanaged.

Quinney: You have to make this someone in government’s job, and it needs to be their only job. Because it’s hard work, and it builds on itself exponentially. So if you care about this, spend a few full-time employees on it. We have seven staff members, but that’s allowed us to create a team of close to 30 with different efforts with universities and agency fellowships. I don’t think we could do that if we didn’t have a few people for whom this is their job. Relative to what we’re doing, we have a small budget. It’s a little over a $1 million to inform how we’re spending $15 billion. We think that’s a good investment.