7 tips for achieving real city innovation in today’s virtual world

Seven months into pandemic-driven city hall experiments in remote work, this much is clear: Online meetings are a challenge.

Whether you facilitate virtual gatherings or just attend them, it’s simply harder online to ignite energy, read body language, avoid distractions, and bring people into a conversation. It’s even more difficult when the goal of the gathering is to spark creativity, generate ideas, synthesize collective intelligence, and build a collaborative spirit.

The good news for city innovators is that everyone is getting a lot of practice trying to make the best of Zoom, Microsoft Teams, Slack and all the other locomotives of virtual meetings and messaging. Meanwhile, they’re getting familiar with new virtual collaboration tools aimed at awakening the same generative group energy that comes from writing ideas on sticky notes and shuffling them around on a wall.

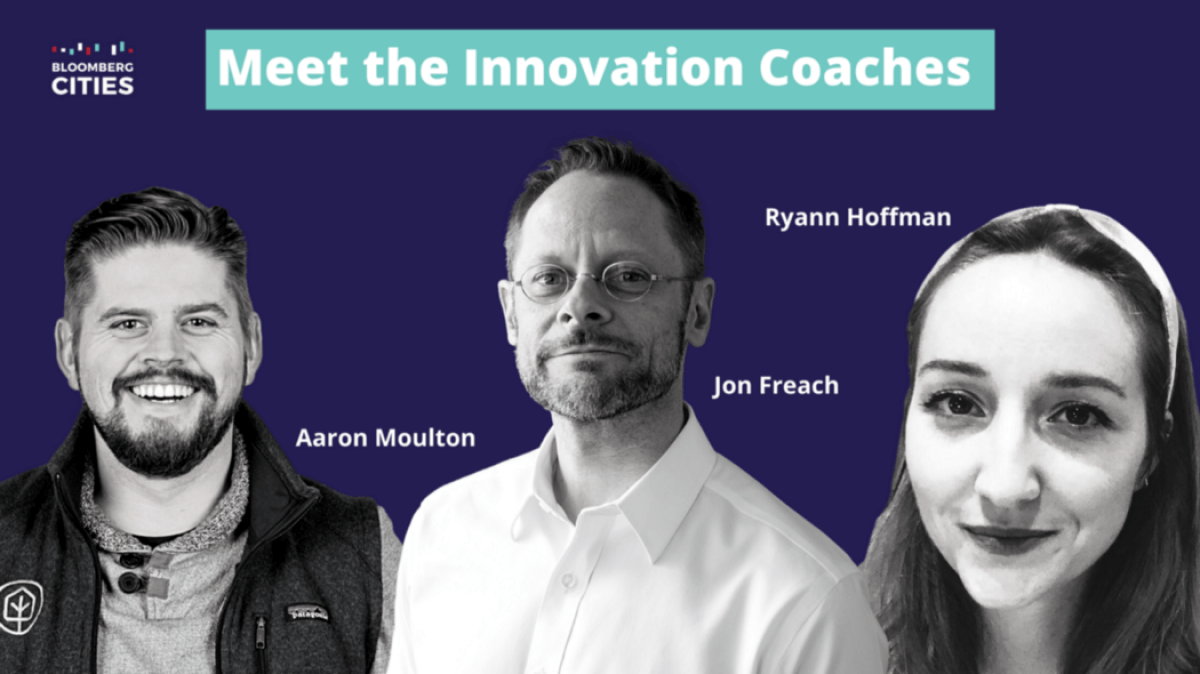

To help city leaders get even better at collaborating through the pandemic, we spoke with innovation coaches currently engaged with city hall teams across the country via innovation trainings sponsored by Bloomberg Philanthropies. These experts in human-centered design offered a number of tips for everything from navigating the latest tech tools to fighting Zoom fatigue.

1. Use collaboration software. In normal times, city hall innovators need their “war room” — a physical space where teams working on a problem meet with stakeholders and residents to draw insights from research, generate and test ideas, and co-create solutions together. Usually, the walls of these spaces are lined with foam boards covered in colorful sticky notes.

A number of software tools now exist to roughly re-create that experience online. The two most popular ones are called Miro and Mural. They offer a sort of blank canvas where people working from anywhere can post virtual sticky notes that can be moved around and commented on as ideas develop. This can happen as a communal effort in real time over Zoom, or asynchronously as team members’ schedules allow.

Although a lot of digital tools aren’t worth the trouble, these are, said designer Ryann Hoffman, a principal with the firm Staircase Strategy. “It’s worth it to make the investment, to change habits, and go through the pain of bringing people along,” she said. “As a facilitator, you can construct experiences where people feel super-heard, where you can flatten the interpersonal dynamics of extroverts versus introverts or big talkers versus people who are more quiet. It makes a really big difference in terms of how people feel they can show up and feeling like they can put their words in.”

2. Don’t overload on tech. For remote work, teams need to be able to do three things: schedule and hold meetings, communicate, and build things together virtually. The software market is awash in tools to help teams do each of those things; it’s important to settle on ones that do the job you need and not keep adding more. “When you keep adding tools into the mix, it adds more content to manage and makes it more difficult,” said said Jon Freach, an independent designer who teaches at the University of Texas. “Less is more.”

The same goes for functionality within these tools. Miro, for example, can do hundreds of things, said Aaron Moulton, a designer with the firm Malgam. But in his work with cities, Moulton only uses a handful of features. “When someone comes into the tool for the first time, they often get overwhelmed,” he said. “It’s really just a few things you need to worry about. Add Post-Its. Make a comment. That’s all we need to focus on. It diffuses the intimidation of it.”

3. Take time to train people on the technology. For some city employees, using new collaboration tools comes easy. For others, it can take a while to build fluency. It pays to build in time to train people who don’t pick it up immediately.

Moulton likes to build some of that training into icebreakers he uses to start virtual sessions. He might ask team members to reflect on something simple, like what they had for breakfast, and then share it on sticky notes in Miro. “It’s building these little moments of habit and practice that make people more comfortable,” Moulton said. “These mini-tasks boost everyone’s abilities.”

Moulton also recommends that teams designate one member to be a sort of technology lead who can become the resident expert in collaboration tools and help colleagues who are struggling with them.

[Read our explainer on human-centered design]

4. Get physical. To kick off a collaborative virtual meeting, Freach likes to use icebreakers that get people engaged and energized. One he likes is called “That’s not krumping.”

Basically, Freach will make some odd shape with his body and tell everyone on the Zoom: “This is krumping.” Then he’ll tag someone by name, who has to say, “That’s not krumping — this is krumping” before forming a different odd shape. It goes on like that, absurdly, all the way around the gallery view. “There’s this jovial disagreement, and it’s funny,” said Freach, who got the idea from this list of Zoom icebreakers. “You get your body moving, and you engage each other. It just changes the mood, and creates the proper weather in the digital room for you to get into the agenda.”

Hoffman also likes to find ways to break the video-screen wall. She’ll also lead stretching exercises, or ask people to write a word on paper and hold it up to the camera, or do a show-and-tell with an object around them. “Bringing peoples’ physical environment into the digital experience is just more grounding,” she said.

5. Acknowledge Zoom fatigue. Spending hours every day in online meetings is exhausting. Hoffman thinks it’s OK to name that up front — “Hey guys, this is going to be tough.” She also said facilitators need to narrate what’s going on more than they might in an in-person meeting because dead air saps energy. “We’re not in the same physical space, and the camera is just a millisecond off, so when you blink it’s not quite when you actually blink, and all of our senses are off and how we read each other and find trust in each other are warped,” Hoffman said. “I find narrating more than you’re used to adds a lot more cohesion in the group.”

Moulton has taken to cracking down on multitasking during creative group sessions online, asking people to put their phones away, turn off their Slack notifications, and not check their email. He also promotes a counter-intuitive strategy for how to combat Zoom fatigue. Instead of scheduling lots of formal meetings over Zoom, he likes to schedule two- to four-hour blocks of “open channel” time for fluid conversation and collaboration with colleagues.

“Having the open channel de-formalizes this new video normal that we have now,” Moulton said. “When you classify everything as a meeting, that means everyone feels a bit more ‘on.’ There has to be a specific agenda that they’re serving. It just elevates the stress of things a little bit. This is trying to recapture some of the fluidity of the workplace where people just walk through and share ideas.”

6. Know when you need to go out in the field — and wear a mask! An important piece of the innovation process is research — to dive deep into a problem the city is trying to solve by understanding fully how residents experience it. That relies on tools borrowed from anthropology such as observation, interviewing, and building empathy for their experience. Some of that can happen virtually, Moulton said. If you were researching food security, for example, you could ask residents to keep a photo journal of their trips to the grocery store or what’s in the refrigerator.

But some research is best done in person. For one thing, residents who need to be interviewed may not have internet or computers to do video calls. For another, there are things you learn by interviewing someone in their home or workplace that you don’t get through a screen. Still, it can be awkward putting on a protective mask and face shield — and asking a resident to do the same — for an interview meant to go deep into their personal experiences. “We have to work harder to build that rapport by spending a bit more time with people, and defusing the situation with self-deprecating humor about how ridiculous this situation is,” Moulton said. “I don’t think we’ve figured out how to be good ethnographic researchers in a pandemic yet.”

[Read our explainer on innovation research methods]

7. Be flexible. A saving grace of the innovation process is that some amount of failure is expected. It’s often by seeing how things don’t work that we come up with better ideas for what does. Approaching collaborative online meetings with that in mind can help relieve the pressure of all the inevitable internet glitches and forgetting to unmute. “It’s important to set a clear ground rule that stuff like that is going to happen,” Freach said. “And that’s OK.”

Hoffman adds: “You’re in this constant state of messing up just a little bit, or having things not going exactly how you want them to go — and it’s a good lesson to just roll with it, and have grace and humor and recognize that you’ll have to figure out something next time. The spirit of the work we’re trying to do in innovation is really tested in trying to move online in a way that is faithful to the work and faithful to the creative spirit of it. This is all about trying to do something a new way.”

Photo courtesy of Shutterstock