Why cities should put equity at the center of their COVID-19 response

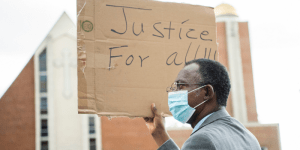

The injustices that are fueling sustained protests across the U.S. are deeply intertwined with racial disparities that are heightening the impacts of COVID-19 among people of color.

That was one of the key messages discussed yesterday as part of the first coaching and training sessions in Bloomberg Philanthropies’ Leading Economic and Social Recovery Series. Dr. Georges Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Association, told nearly 400 mayors and city leaders gathered that African-Americans who are taking to the streets in protest aren’t ignoring the risk of COVID-19. Rather, he explained, they’re weighing the risk of infection against their own risk of facing police violence and making an ethical decision to protest.

“These folks are balancing that risk,” Benjamin said, citing a new poll finding that nearly half of Black Americans say they have, at least once, felt their life was in danger because of their race. “If I’m younger, I might be more likely to die of police violence” than COVID-19, he said.

Benjamin then laid out some of the ways racism is impacting the COVID-19 response and contributing to the disproportionate toll the disease is taking among African-Americans.

Structural racism was baked into many of the initial choices around testing, he said. For example: Testing locations were not located in minority communities and set up as drive-through operations for people with access to a car; long lines discouraged people who couldn’t take off work; a doctor’s orders were typically required, turning away people who have less access to doctors or can’t afford co-pays.

There’s also internalized racism in the way Black Americans are experiencing the COVID-19 outbreak, Benjamin explained. Early on in the pandemic, there was a lot of misinformation saying that African-Americans didn’t get the disease; now that they’re getting it in disproportionate numbers, there’s fear of stigma and reluctance to get tested for fear that a positive result could cost them work and income.

Then there’s interpersonal racism, symbolized most clearly by what Benjamin called “masking while Black.” Citing a case of two Black men who were kicked out of a Walmart for wearing masks, Benjamin said African-Americans face risks while simply following public-health guidance. “They’re concerned people will profile them because they’re of color and they have a mask and are therefore viewed as a threat,” he said. “These stories are real.”

As former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg opened Thursday’s sessions, he reminded mayors that the fight against COVID-19 and for racial justice are not distinct from each other. “The virus hit communities of color the hardest,” Bloomberg said. “So by continuing to focus on responding to and managing COVID-19, you’re also confronting issues of equality and injustice.”

As mayors continue to confront these crises, Benjamin called on them to look for ways to put equity at the center of their response and public outreach, particularly as the emphasis of the pandemic response shifts to widespread testing and contact tracing. “We need to do that in an equitable manner and build trusted messengers,” he said. “Because if you call me on my phone today and tell me I’ve been exposed to the virus and ask me all this personal information, I’m probably not going to give it to you unless the person on the phone can build some trust with me.”

He also called on mayors to play a role in building unifying messages around the public health response. “We’ve got to normalize masks, physical distancing and hand hygiene so that people think it’s cool,” Benjamin said. “Many of the people who are opposed to wearing masks would not think twice about wearing a hardhat on a work site. I would argue that people want to be safe. I want to protect me, and I want to protect you. Therefore, I should wear the mask.”