Unpacking the secrets of culture change in city halls

(Shutterstock)

Helping city leaders integrate innovation tools like data, collaboration, and resident engagement into their city halls is a big part of Bloomberg Philanthropies’ mission.

It’s also at the heart of a new guide for mayors and staff working to change organizational culture in city hall. Published by the Bloomberg Harvard City Leadership Initiative, the 34-page City Leader Guide on Organizational Culture Change is a playbook for local leaders who want to go beyond piecemeal initiatives to fundamentally change the way things work in local government.

The authors, Neil Kleiman and Alexander Shermansong, both teach at New York University’s Robert F. Wagner School of Public Service. They say the literature on public-sector culture change is scant when compared to all the books and magazines devoted to culture change in the private sector. They set out to change that.

“We were really surprised when we went into this,” Kleiman says. “For as much as people talk about culture change in local government, no one’s really written anything on it.”

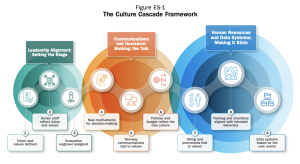

The new guide includes a practical nine-step framework for how to transform workplace culture inside city hall, which Kleiman and Shermansong call “The Culture Cascade.” There’s also a diagnostic tool and worksheets for city teams to assess how they are doing on each of the nine steps, as well as deeply researched case studies of mayor-led culture-change efforts in Kansas City, Mo., Louisville, Ky., and Somerville, Mass. Best of all: It’s a really good read.

Bloomberg Cities caught up with Kleiman and Shermansong recently to learn more about culture change and how it can enable public-sector innovation.

Why does the culture inside city hall matter?

Neil Kleiman: A lot of people think that what's holding cities back from significant reform is funding, technology, staffing—and obviously, those are issues. But when we talk to mayors and ask what their biggest obstacles are, five times out of 10 they’ll say it’s the culture of the organization itself. The mayor may want to embrace data and technology but then you go and talk to the staff, or even at the deputy commissioner level, and you get a glazed look that says: That’s not how things get done here.

Where it really hit me while working on this was when there was a lot of upheaval around criminal justice, and The New York Times had a piece bringing five experts together to discuss what we can do to address dysfunction in our police departments. Across-the-board, the answer was the need to change the culture. You're not going to change policing just with some legislation, or some new funding, or changing incentives, as much as you have to do all of those things. You have to get at the culture of policing.

In the private-sector literature, there’s consensus that culture determines how work gets done. It determines how people do their jobs on a daily basis, on a monthly basis, on an annual basis. So in that regard, it's everything.

Is changing culture at city hall only an internal matter, or is it something residents can feel?

Alexander Shermansong: It does matter to residents, because the culture suffuses every single interaction they have with government, whether you're a victim of a crime reporting it, or you're alleged to have committed one. It’s how you're taxed, how your kids get schooled, whether potholes get filled—the culture goes through all of that. And if you're dissatisfied with any of those things, culture is the root of that experience. Culture change is critical to getting the type of municipal government that residents expect and deserve.

In the guide, you mention celebrated workplace cultures at companies like Disney or JetBlue. Are there lessons cities can learn from the private sector?

Shermansong: There's a lot cities can learn. In the private sector, there’s a lot written about how to analyze your culture, how to design culture change, how to implement it. There are two things that are pretty close to universal in those efforts.

One is that the leadership—the CEO and the senior leaders—talk about the company’s values and are seen to care about the values. They actually live them. At Amazon, for example, Jeff Bezos would want people to be prepared at meetings. So he’d take the first few minutes of a meeting for everyone to read a memo together.

The other thing is when you look at most corporate hiring pages, they talk about the culture of the organization. They're using culture as a way to determine who they want in the organization and who gets promoted.

What’s different in cities?

Shermansong: One, the chief executive is elected. So the values and behaviors that determine whether that person gets the job are around campaigning, not managing or governing.

Second is the hiring side. You have an incredibly long-tenured workforce, and civil service rules and collective bargaining agreements in many jurisdictions. Changing what it means to hire a garbage collector in New York is a five-to-seven year undertaking over the course of planning it, negotiating with the union, and implementing it.

One thing we saw in the private-sector literature that is not common in the public sector and maybe doesn't need to be is monetary incentives. By and large, government employees are motivated by mission and by impact and not by financial bonuses. So to use those is not necessarily going to be the right way to motivate them.

Kleiman: Compared with other levels of government, cities are completely analogous to the private sector, because they’re actually interacting with customers, or citizens, all the time. They’re basically like a company that provides services. Culture is intrinsic to doing their job effectively in a way that you wouldn't necessarily see at the state or federal level. So, in that regard, cities are wholly appropriate for doing this. And it's long overdue that we have a thoughtful strategic framework for taking it on.

Is it possible to change the culture in local government?

Shermansong: Very much so. One of the great luxuries of public-sector leadership is you do get four years—and you might get eight or more. That's why Neil and I are saying: Start right away. If you start on day one, you can make a huge amount of difference.

Kleiman: It is possible. Not to have a complete turnaround in two years, but it is possible to begin to move the culture in a positive and healthy direction. In the three cities we elevated, we’re not saying they 100-percent turned their culture around. But what we were really encouraged by is that they got a good bit of the way there.

In the guide, you give local leaders a nine-step framework for change, which you call the “Culture Cascade.” What’s the main idea here?

Shermansong: We kept hearing that culture is a problem, but we didn't find anything on what to do about that problem. So we wanted to create something that’s practical and actionable, a common path local leaders can follow even though each city is complex and very different.

There's a lot of different things that need to get done, in roughly three buckets. The first is around leadership and getting the leadership team aligned around certain values and behaviors. Once you get that, it’s about expanding into the organization to create change around how decisions are made and communicated. And then when things are headed in the right direction, it’s how you bake those systems and policies into the everyday operations in human resources and information technology. We find analogs for most of these in the private-sector literature.

What are traits you see in a city hall culture that values innovation?

Shermansong: One is an absolute thirst for new ideas, wherever they come from—good or bad, just constantly looking for new ideas. And then those that are good, building on them. It’s about always being hungry to try things.

Second, we see a relentless focus on optimizing daily operations—no matter what you’re doing today, what’s one way we can be doing even better tomorrow? So just relentlessly focusing on some incremental improvement. Often, that’s accompanied by data showing that progress is actually being made.

Kleiman: We also see a focus from the top-down to the front lines. You really need the entire enterprise moving in a direction of new ideas and feeling like they're supported in doing things in a different, creative way. That's never going to happen if the culture only exists within what I call the “A-team,” which is the innovation team and the few chiefs around the mayor. It's those municipalities that really go out of their way to consistently bring in everybody in the enterprise that are supporting a culture of innovation.

What lessons jump out from your case studies about how cities can enable a culture of innovation?

Shermansong: Somerville focused on bringing in external talent. Don't worry if someone is Somervillian or not when you bring them into the role. That was from day one. And the mayor every month celebrated a new idea.

Louisville did massive amounts of training, giving a huge portion of the workforce digital skills and problem-solving skills, which were the same things that the mayor personally was using in his interactions with direct reports and departments. So the skillsets they inculcated in the rank-and-file reflected the way he was running things at the top. Training is one of the most impactful things one could do and often costs a lot less than people imagine.

And Kansas City has its annual survey of residents. What was so innovative about their approach is they embedded the survey into budget decisions and into operating decisions that departments were making. They made it real for rank-and-file employees and for managers, because it oriented whether you were considered to be doing your job well or not, and whether your department was getting resources.

What can mayors do to ensure that culture change endures beyond transitions?

Shermansong: One is hiring and promotions. The more that people are hired and promoted based on cultural aptitudes and mindsets, the more likely those are to persist in the organization. Another is creating standard operating procedures, and even organizational structures around it. For example, to boost community engagement, Somerville created an external panel that recommends key appointments. A new mayor would have to actually get rid of that, as opposed to letting it just seep away.

Kleiman: On day one, a mayor needs to be thinking about their exit. Even when you're in a transition, you need to think: What's the headline you want written when you leave? How do you imagine embedding and enduring your priorities, your culture, your values? It's remarkable how much that changes your management approach if you stop for two seconds and think about it. In the private sector, that’s non-negotiable—it's a requirement that you think about your exit memo the day you start the job.

You say in the guide that local leaders often mistake promising new initiatives for culture change. What are some examples of that, and how can local leaders tell the difference between the two?

Shermansong: A favorite in both the public and private sectors is coming out with mission statements and value statements, and posting those by the elevator or on your website. That's not culture change. You actually have to live the values for it to be culture change. It has to be how you actually make decisions, especially in a crisis. It has to be how you actually allocate resources.

The second is mistaking strategy for culture. You can come up with a great plan with a list of initiatives and metrics and resources associated with those. But that's not the same as changing the culture.

Kleiman: It's the “what” versus the “how.” Going back to police departments, you can say, “We have a commitment to have more community-oriented and resident-responsive policing.” Okay. That's the what—and that's great, I'm all in on that what. How are you gonna do it? That's culture change. That's how you do it.