Unleashing civil servants to innovate

By James Anderson, Bloomberg Philanthropies Government Innovation program lead

The public-sector innovation movement has made great gains over the past decade. Governments around the world have set up innovation teams, labs, and funds to spur creativity and encourage risk-taking. They’re using behavioral insights, big data, and citizen-sourced data to inform decision-making like never before. And they’re applying human-centered design and using prototypes to solve problems alongside residents.

As inspiring and hard-won as these developments are, they represent only the tip of the iceberg of what’s possible. While city-hall decision makers are increasingly adopting the tools of innovation, those tools have yet to seep into the DNA of public-sector organizations or change how frontline employees and mid-level managers do their jobs.

Across my work in—and with—local government, I’ve always experienced these civil servants as natural and willing innovators—iterative in the face of daily resource constraints, responsive to demands from city hall, and adaptive to needs on the ground. They’re also passionate about improving their communities and hungry for ways to do that better.

That’s why I’m so excited about an innovation skills initiative we’ve rolled out in more than 40 cities. It’s focused largely on rank-and-file civil servants selected from different agencies, who come together to work on a problem chosen by the mayor. Over nine months, these teams get intensive coaching on techniques of human-centered design that helps them deeply engage residents in their research and idea development. The results have been remarkable.

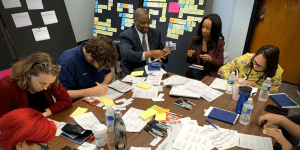

In New Orleans, Mayor LaToya Cantrell sent a cross-departmental team including people from the public works, finance, and water departments. Their task: Find ways to build the public’s trust. They came up with more than 200 ideas, including one they’re especially enthusiastic about: Adding “why buttons” to signage near infrastructure projects to provide a plain-English explanation of why the project is needed and how long the construction will last.

Stockholm Mayor Anna König Jerlmyr asked her team to invigorate a disinvested neighborhood called Skärholmen. They came into the project believing the area’s negative reputation was what was driving businesses away. But they heard a different story from residents, who blamed local government for neglecting their neighborhood. Together, the city team and residents came up with an idea the city plans to launch this year: an innovation hub on the neighborhood’s main square that includes co-working spaces for businesses and gathering spaces for community events and festivals.

And in Madison, Wis., Mayor Satya Rhodes-Conway asked her team to boost equitable alternatives to getting around the city by car. In interviews with residents, they found that the city’s bikesharing system—with docking stations mostly in the city’s affluent core—was not much of an option for people of color in outlying neighborhoods. They came up with an idea that appears to be a first in the U.S.: the “universal basic bike.” The plan is to lease residents electric bikes that they can keep, at a very low or no cost. Mayor Rhodes-Conway says she’s excited to see these newly acquired innovation skills now infusing other areas of the city’s work.

It’s been nearly 250 years since economist Adam Smith first observed in his book The Wealth of Nations that front-line employees were well positioned to find hacks that improve efficiency. That idea is as true today as it was in the 18th century and, as the city hall teams are proving, as relevant to the public sector as it is in the private. Now it’s time we unleash these frontline teams by giving them the tools and permission to improve city services from the ground up.

(Photo: A cross-departmental team in New Orleans meets—before the pandemic—as part of a training in innovation techniques)