‘Teaming’ in and out of City Hall

All mayors have their trusted advisers, department leaders, and senior staff — the core team who keeps City Hall running, day in and day out.

All mayors have their trusted advisers, department leaders, and senior staff — the core team who keeps City Hall running, day in and day out.

If every mayor has a team, however, not all are adept at “teaming.” That’s a dynamic activity, where you’re pulling together people from different backgrounds to diagnose a problem, learn quickly, and work together to find solutions. Teaming is a critical public leadership tool, whether you need to solve urgent problems quickly or to seek breakthrough innovations to address complex urban challenges over time. And as I discussed this week with the 41 mayors starting a year-long leadership and management program with the Bloomberg Harvard City Leadership Initiative, it’s a skill they and their senior leadership want to get better at.

As we seek to better understand the role of teaming in addressing the complex social issues facing mayors and their cities every day, my Harvard colleagues, Hannah Riley-Bowles, Jorrit de Jong, Eva Flavia Martinez Orbegozo, and I have launched new research as part of the Bloomberg Harvard program. Through new analysis of work in cities, we are seeking to observe and identify the enablers of and barriers to successful cross-boundary teaming in cities.

What’s the difference between a team and teaming? In short, “team” is a noun — a group with fixed membership. “Teaming” is a verb — it’s something you do on the fly.

Think in terms of basketball.

The Golden State Warriors are a team — a group of individuals who always play on the same side. They learn their plays, get synced up on strategy, and grow accustomed to each other’s style of play. And the team is their full-time job, so they have plenty of time to practice together.

Teaming is like a pickup game — individuals from different backgrounds, coming together to play for a short time. They may not know each other at all, let alone one another’s strengths and weaknesses at basketball. They need to get up to speed quickly, and be adaptable, to succeed.

Outside of sports, working in teams is common — and government is no exception. There are good reasons for that. Well-led teams develop a shared sense of purpose that supports their everyday work. Members become familiar with each other, both as people and as professionals, and learn whose skills can be useful to the group. They also can establish a common language for situations they encounter and develop preferred ways of resolving conflict and holding each other accountable.

However, teams often might not be practical for fighting drug addiction, improving schools, or solving many of the complex problems common in cities. Innovation in this setting requires convening multiple perspectives — often from across city agencies or from partners in the nonprofit, business, university, and philanthropy sectors — to look at things from different vantage points and work together to discover new solutions. The people brought together to innovate already have other roles and responsibilities — and aren’t expected to stop what they’re doing to join a new team full time. Rather, they are asked to contribute ideas and skills and to be willing to help test and implement new possibilities. Different expertise will be needed at different times — and often in ways that are impossible to anticipate in advance. That’s a perfect setting for teaming: when you need different sets of expertise, skills, and resources, at unpredictable times, to get things done.

This can be a lot harder than it sounds. Just as it may take a pickup basketball team a while to find a groove, it takes cross-agency or cross-sector teams time to get on the same page. Put a police captain, housing officer, and social worker together to work on homelessness, and each will likely come with his or her own assumptions about what changes are needed and each brings his or her own language or jargon for describing them. Logistics are also a challenge — everything from finding a time and location for people to meet when needed to figuring out how to conduct research, share expertise, design experiments, and consolidate learnings. Those issues can be tricky when people are operating outside their normal hierarchy.

[Read: Meet this year’s class of Bloomberg Harvard mayors]

To address these issues, you need a good team leader — someone to own the mission, organize meetings, keep the attention of those contributing to the initiative, and ultimately deliver its results. In the city government context, that person is often in City Hall, ideally close to the mayor’s office, where the authority to convene cross-agency and cross-sector partnerships is clear.

What else is needed for effective teaming? After studying examples from across many industries, I’ve seen four key practices emerge. (For more on each, read my Harvard Business Review article, “Wicked Problem Solvers”):

Teaming requires an adaptable vision. This means providing space for team members to shape and influence where the project goes, acknowledging pivots when they happen — all the while remaining true to the underlying values of the project.

Teaming needs psychological safety. Team members need to feel safe voicing ideas, even if those ideas might seem obvious to other team members with more issue-area expertise. They need to believe their thoughts are welcome in the teaming arena. Everyone’s ability to maintain curiosity and an open mind is key.

Knowledge sharing across silos has to be facilitated. Pulling in expertise from different fields is the point. Making sure those diverse perspectives are heard and understood takes effort — because this doesn’t happen automatically.

Teaming requires experimenting and learning. The process is necessarily iterative. In a collaboration designed to come up with brand new solutions, there’s obviously no blueprint to follow. It’s crucial to be willing to put new ideas to a test, so as to learn quickly and keep going, or else adapt and try again.

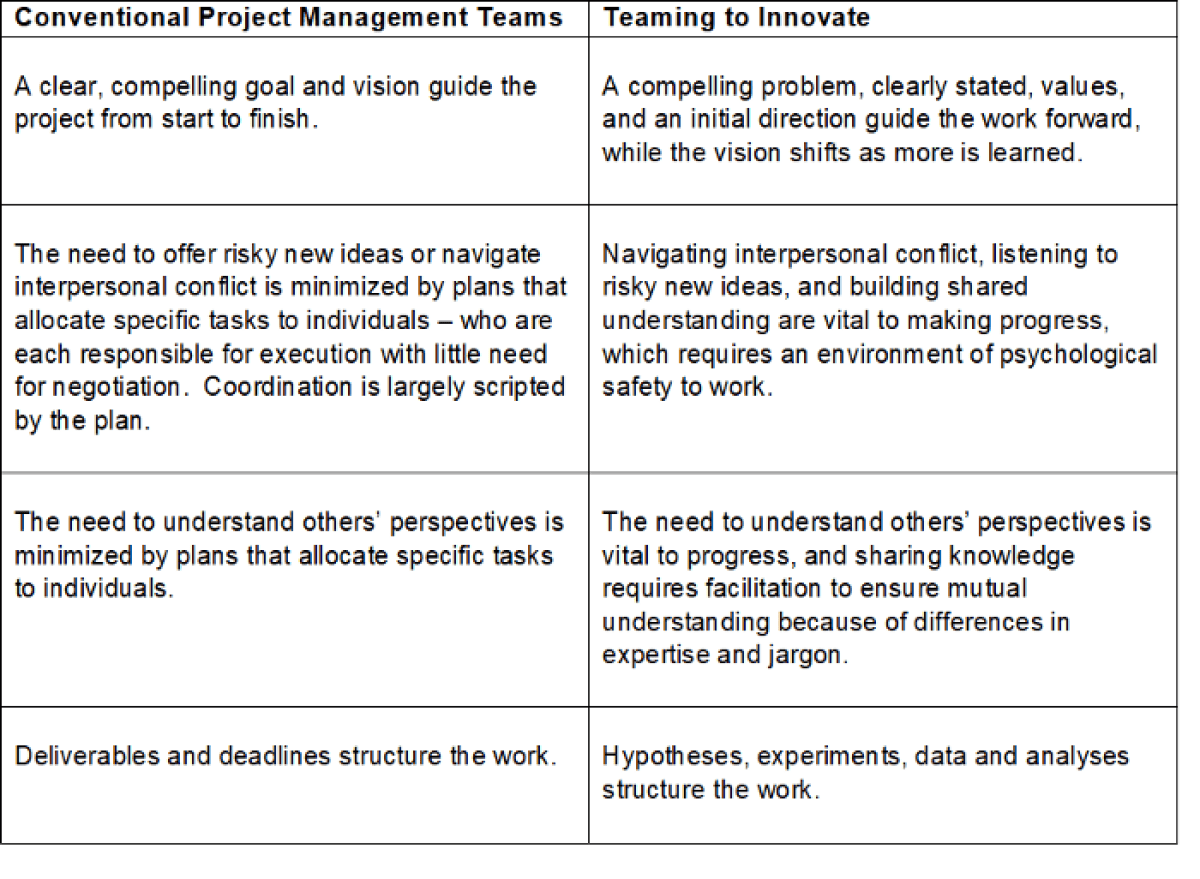

These four practices exist in subtle, and occasionally striking, contrast to the management of conventional project teams. The table below lays out the differences between teaming practices with those of conventional project management.

[Read: How mayors lead: Emerging insights from the Bloomberg Harvard City Leadership Initiative]

And that gets us to one way in which teaming is not like pickup basketball. Where a pickup game might feel loose, informal, or unstructured, teaming well requires a good bit of intention. It’s messy but disciplined. It’s an unpredictable but structured learning process. Teaming involves bringing people together in a deliberate and thoughtful way, so that their diverse experiences can lead the group to see a problem in an entirely new way.

Amy C. Edmondson is the Novartis Professor of Leadership and Management at the Harvard Business School, a chair established to support the study of human interactions that lead to the creation of successful enterprises that contribute to the betterment of society. Her books include “Teaming: How organizations learn, innovate and compete in the knowledge economy” and ”The Fearless Organization: Creating Psychological Safety in the Workplace for Learning, Innovation and Growth.”