Mapping innovation: Five takeaways from 89 cities around the world

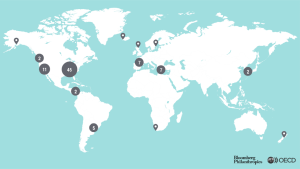

A recent study of urban innovation efforts by Bloomberg Philanthropies and the OECD used survey data from 89 cities around the world.

Weeks after releasing a report and interactive map tracking the proliferation of innovation methods in city halls around the world, Bloomberg Philanthropies and the OECD are urging more cities to “get on the map,” both to assess their own innovation efforts and build a global understanding of how the urban innovation movement is spreading and maturing.

Based on findings from a survey of 89 cities, from Anchorage, Alaska, to Wellington, New Zealand, the map provides the most thorough accounting yet of how local governments are building internal capacity to solve problems in new ways. The research is an ongoing effort: Cities that weren’t part of the initial survey — or have only just begun a push on innovation — haven’t missed the chance to get counted.

“This is a great opportunity to build a comprehensive understanding of the scope and scale of innovation happening in city halls around the world,” said Stephanie Wade, lead for innovation programs at Bloomberg Philanthropies. “By becoming part of this research, cities can see how their innovation efforts compare with other cities, and also find and build relationships with peers to share lessons learned.”(Click here to learn how to add your city to the map.)

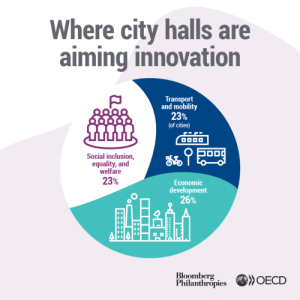

Already, this research has produced findings that city leaders can use to shape their own strategies for testing out new ideas, partnering with outside organizations, using data to guide decisions, and engaging residents in problem solving. Here are five takeaways from the 89 cities surveyed so far:

1. Becoming an innovative city doesn’t happen by accident

While city halls often experiment with innovation organically, as a result of someone getting frustrated with the status quo and wanting to try a different approach, building innovation capacity for the long haul requires intention. And that often starts at the top by building a strategy for innovation that transparently communicates how a city wants to build innovation capacity and how they want to use it to improve services. However, only about half of the cities surveyed have this type of a formal innovation strategy.

Having an innovation strategy empowers cities to use innovation approaches such as human-centered design, for example. They also are more comfortable with taking risks and pursuing organizational change. Kansas City, Mo., Peoria, Ill., and Stockholm, Sweden, are noted in the report for having innovation strategies to guide their work. For example, Kansas City focuses innovation efforts on improving operational efficiency, customer experience, and citizen engagement.

[Read: How to make innovation capacity stick for the long haul]

2. Support from top city leaders is critical

Innovation means trying new things, which can be tough to do in the public sector. That’s why support from mayors and city managers is so important. When city employees know leadership has their back, they can pursue new ways of working more freely. Four out of five cities surveyed said that political and managerial leadership is essential to supporting innovation capacity. As the report notes, “City administrators, city managers or chief executives set the standards for how audacious civil servants can be in developing new approaches and projects.”

Among cities that have dedicated innovation teams, half sit in the mayor’s or city manager’s office, although “there’s no one-size-fits-all approach for the location of innovation units within city administrations,” the report says. “When cities see innovation as a powerful tool to foster cultural change in the administration and want to strengthen coordination, they usually establish the unit in the mayor’s office. When cities want to focus on a specific area — such as economic and social development, environment, transport, or housing — they tend to locate this unit in a specific department.”

3. Cities are dedicating staff time and financial resources to innovation

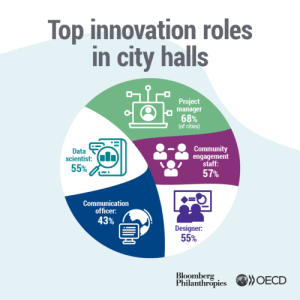

Among the cities surveyed, about nine in 10 have staff or teams dedicated to pursuing innovation. They’re people with a range of skills, including project management, community engagement, human-centered design and data science. In most cities, innovation staffing accounts for fewer than ten people, although there are some large municipal innovation units out there. For example, the New York City Mayor’s Office for Economic Opportunity (NYC Opportunity) — an innovation lab focused on reducing poverty and increasing equity — includes 60 staff.

Along with staffing comes funding. While cities have leaned on foundations and even private-sector investments to kick-start innovation efforts, four out of five cities surveyed said they now have specific funding in place to support innovation capacity.

4. Building data capacity is a critical component of boosting innovation

You can’t come up with an innovative solution if you don’t fully understand what the problem looks like. That’s why cities need good data, both quantitative and qualitative, up front. They also need data to show whether new approaches are working. The city survey backs this up. “Cities with a high-level use of data seem to be more familiar with innovation practices,” the report says.

Most cities have a lot of work to do in this area. Fewer than one in three cities reported having the data they need to drive focused and effective innovation when it comes to work on blight, social services, or equity. But the report also points to big progress in cities such as Chelsea, Mass., and Seattle, and notes the potential of initiatives like What Works Cities Certification to set a standard of excellence for cities to aim for. One place cities can look to for help is universities. Of the surveyed cities that claimed data play a key role in their innovation work, 75 percent have established partnerships with academia and think tanks to improve data management.

Data is not only numbers. It’s also qualitative research with residents and stakeholders to understand the root causes of complex problems and deeply understand what residents need. According to the survey, cities that hired innovation staff with skills such as human-centered design are more effective at engaging residents in new ways. That means these cities are getting better at focusing on the parts of the problems where they can make the biggest impact, and engaging the community as co-creators to make sure they implement new services, programs, and policies that truly make a difference.

[Read: Meet the new force shaking up city halls: designers]

5. Cities must do more to evaluate the impact of their innovation investments

As innovation practices take root in city halls, there’s a growing need to ask the question: Is it working? Are investments in new ways of solving problems paying off? While anecdotal evidence of success abounds, cities have a long way to go to prove it. Only 16 percent of cities with formal innovation goals said they’re comprehensively and systematically evaluating the impact of this work.

Cities identified a number of barriers to evaluating innovation work. There’s scarce resources and technical capacity to do rigorous evaluation, for example, as well as political dimensions to consider when an innovation process fails to produce big wins. But it’s worth pushing forward in this area, said Wade of Bloomberg Philanthropies.

“For cities to make a real commitment to innovation, they have to hold themselves accountable to the work they’re doing,” Wade said. “It means making sure it’s actually having the impact they intend it to, and that they’re effectively using public resources to truly improve the lives of residents.”