Lessons from Chicago’s COVID-19 Racial Equity Rapid Response Team

The numbers told a disturbing story from the very beginning of the coronavirus outbreak in Chicago. Of the first 100 Chicagoans to die from COVID-19, 75 were African-American.

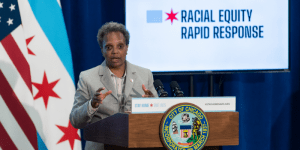

Mayor Lori Lightfoot and her team decided that disproportionate impact needed an immediate response. So they created the city’s Racial Equity Rapid Response Team, one of the nation’s first initiatives dedicated to mitigating the devastating toll the pandemic has caused in communities of color. City leaders across the country have been watching the effort closely as they move to address racial and ethnic disparities with COVID-19 in their own communities.

Lightfoot told CBS This Morning last week that it was important for her to create such a task force because of her personal connection to the community. “When I first saw those numbers about how black Chicago was being disproportionately impacted, my first reaction was to think about my 91-year-old mother,” Lightfoot said. “To think about my siblings who are all over 60, some of whom have these underlying conditions. It felt very personal to me.”

Candace Moore, the city’s first Chief Equity Officer, told Bloomberg Cities that the mayor’s charge to her was to “be transparent and own this moment with the community and get this information out there, but that we also had the responsibility to do something.” Moore added: “Even as we understood that these numbers were heavily impacted by institutional inequalities that existed long before this pandemic, there had to be something meaningful we could do right now.”

That “something” was to create a public-private partnership with community groups that had already been providing healthcare supports, mentoring services, and community organizing. Moore said the partnership began with the realization that “our overall public-health approach and strategy was not going as far and as deep as it needed to go. And to do that, it would require us to get into partnership with organizations who were on the ground in those areas to listen, learn, and respond much faster and more intensively.”

[Get the City Hall Coronavirus Daily Update. Subscribe here.]

The goals of the response team have been to “flatten the mortality curve in black and brown communities and create the infrastructure from which we can build future work,” Moore said. “This can’t be a one-and-done — we need to lay the track for future work.”

The initiative has focused so far on three areas where local COVID-19 data indicated a need for action — Austin, Auburn Gresham, and South Shore — though it has broadened to a more regional approach in recent weeks to include hard-hit Hispanic neighborhoods as well. Moore said the work is organized around four central themes:

- Education and outreach: One crucial problem was that residents in these communities were not getting clear and scientifically sound information on how to protect themselves and their loved ones. To respond, one strategy the team used was to hold virtual town meetings in conjunction with trusted community partners.

- Prevention: One key response has been to provide masks. The city, working with private partners, acquired 1 million cloth masks and 750,000 of those will be distributed to the areas being served by the Racial Equity Rapid Response Team. “A huge part of what we’re doing is actually preventing people from getting COVID-19,” Moore said.

- Testing and treatment: Getting a testing facility in each of the targeted areas has been a key goal, Moore said.

- Support services: Moore said the team also has worked to implement supportive services to help residents feeling the impact of the pandemic in other parts of their lives, whether that be food insecurity or housing. One response has been to work with the Greater Chicago Food Repository to stand up food distribution sites in each of the three targeted areas that will provide meals for 1,000 families per week for approximately six weeks.

For other cities considering launching a similar equity response effort, Moore offered three topline lessons learned:

- Work with existing community organizations: “The secret sauce to our work is the communities. The ability to co-create with organizations on the ground is foundational to this approach and to do that and to build relationships and to build trust, that’s the most transformative way to get at these efforts.”

- Integrate the team as widely as possible with other city departments: “This can’t be an effort that goes off in the corner and has no other resources to connect to. Continue to plug this into the many, many tentacles of government.”

- Stay nimble and adaptive: “There is no one-size-fits-all. The ability to be iterative, which can be hard in government, is essential.”

Other cities that are exploring the use of similar racial equity task forces include:

- Boulder, Colo., where the city is using a Rapid Response Racial Equity Assessment tool to help guide decision-making during the coronavirus outbreak.

- New York City, where the mayor has created a task force on racial equity.

- Oakland, Calif., where Mayor Libby Schaaf and regional leaders announced the formation of an emergency task force to immediately address disparate impacts of the COVID-19 virus and create state legislation to reduce health disparities for people of color.

- Pittsburgh, where the city council approved the creation of a racial equity task force last week.