How a handwritten note helped Syracuse collect $1.5 million in back taxes

Sometimes, little things can make a big difference.

That’s one lesson from a stunningly simple experiment in Syracuse, N.Y., that netted the city $1.5 million worth of overdue tax payments.

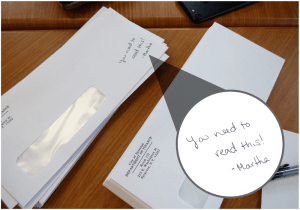

Earlier this year, the city mailed out more than 3,800 letters to residents who were behind on their property tax bills. Half of those letters had a handwritten note on the front of the envelope: “You need to read this! -Martha”. Martha is the city’s finance commissioner, Martha Maywalt.

Checks came pouring in. More of those payments came from people who had received the letter with Martha’s message than those who did not. “You get so much mail,” said Adria Finch, Syracuse’s chief innovation officer. “That handwritten message on the front of the envelope catches your eye and gets you to open it.”

The Syracuse experiment was an example of how cities are applying insights from behavioral science to make government more efficient, effective, and inclusive. Small behavioral “nudges” can go a long way.

For example, Anchorage, Alaska, boosted payments from traffic tickets and other fines, and Chattanooga, Tenn. and Lexington, Ky., increased sewer-bill collections by redesigning letters sent to delinquent account holders. Unlike the legalese of the old letters, the new ones made payment options obvious. Chattanooga and San José, Calif., have used behavioral science to attract more diverse recruits for their police forces, while New Orleans has used text messaging to get more residents to visit the doctor.

Syracuse is lucky to have expertise in these techniques in its backyard at the Maxwell X Lab, part of the Center for Policy Research at Syracuse University’s Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs. The city had also run similar experiments previously via engagements with two Bloomberg Philanthropies programs. The first, What Works Cities, helps cities use data and evidence effectively, including through the use of behavioral insights. The second, Finch’s innovation team, is an in-house consultancy trained to help City Hall solve problems in new ways.

The experiment with back taxes was a collaboration between the city and the X Lab, with funding from the Allyn Family Foundation. The idea was to target property owners who were either delinquent on last year’s property tax bills or late on their current bills. A new letter was developed, with clearer messaging than the typical legal notice the city sends each year.

[Read: Behavioral science is quietly revolutionizing city governments]

Two separate mailings went out, with property owners randomly divided into three separate groups. One third got the letter with the handwritten message from Martha. One third got the letter, but without the handwritten message. And one third — the control group — did not get a letter at all.

The results were clear. Property owners who received the letter were more likely to pay their bill than those who did not. Of those who got the letter, the ones who got an envelope with the message from Martha were more likely to pay up than those who did not. (The X Lab has a more detailed accounting of the methodology and results here.)

In total, across the two trials, the courtesy letters netted the city at least $1.47 million in additional revenue. Just for the sake of comparison, that’s more than enough to cover the city’s annual tab for street cleaning.

Reflecting on Syracuse’s success, Adria Finch and Martha Maywalt offered a few lessons for other cities considering trying something similar.

- Handwriting works. It’s hard to make a letter stand out in the daily jumble of junk mail we all receive every day. The handwritten note clearly helped. Beyond the uptick in payments, Maywalt received multiple phone calls from people who saw the note from Martha and wanted to talk to her about their tax situation. (One man called to complain — it seems his wife, upon seeing the handwritten note, quizzed him: “Who’s Martha?” He said he intended to pay his bill.)

- Readability matters. Compared with the annual legal notice the city sends delinquent taxpayers, the new letter was easier to read, with plain language, a box at the top with big letters saying “pay now,” and graphics showing the ways to pay, such as by e-check or credit card. “It’s very different looking from the usual letters we send out when someone hasn’t paid,” Maywalt said. “The envelope got them to open it and look. The content of the letter got them to read it and act.”

- Have an early and open dialogue with your legal team. The Syracuse effort initially hit a snag with the city’s Law Department. As it turns out, the city is legally required to send delinquent property owners a notice annually, and that letter can play into legal proceedings if the matter ends up in court. The lawyers’ concern: Experimenting with that letter — or not sending one at all in the case of a control group — would violate due process. A workaround was found: The experimental letter was an extra communication, a “courtesy letter” sent in addition to, not in place of, the required one. “It’s important to have an open dialogue with your legal team and ask them what they’re comfortable with and if they have any tips,” Finch said. “If you involve them in the beginning, it’s better in the long run.”

- Beware of writer’s cramp. Martha did not write the message by hand on nearly 2,000 envelopes by herself. Finch threw an “envelope party” in the i-team’s office, with about 20 city employees, including Mayor Ben Walsh, stopping by to pitch in. Music and cookies made it fun. “It stinks to have to write that message over and over again,” Finch said, adding with a joke: “Cookies are the most important part of the whole thing.”

[Read: Making revenue collections more effective: lessons from a Nobel laureate]

Now that Syracuse knows the handwriting works, they’re doing it again. The city recently sent 7,000 letters to people who owe county tax. The Martha message is on all of them. While it will take a while to see the results, Finch said Syracuse’s willingness to test out a new approach, learn from it, and adapt its approach based on the evidence, always pays off in the end.

“We always learn something from these experiments,” Finch said. “We’ll keep doing them, and we’re OK with an occasional failure. That’s the cool thing with these: it’s not a huge investment. We might as well try. If it works, amazing! And if not, then we move on.”