How cities can use text messaging to get more residents using services

“SNAP” is what the federal government calls its program to help low-income Americans put food on their tables. But, as anyone who’s ever applied for the aid knows, getting that help is usually anything but a snap.

The innovation team in Anchorage, Alaska, is trying to change that. And to do so, they’re turning to one of the simplest and most ubiquitous tech tools around: text messaging.

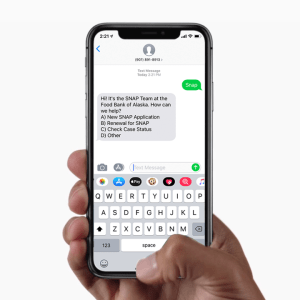

The i-team is piloting a tool that lets residents start the process by texting “SNAP” to a dedicated phone number. That triggers an automated “textbot” to respond with a question: “How can we help?” By messaging back and forth with the user, the system learns what the person needs — for example, to submit a new application or renew an existing one — and collects a few more details like the person’s name and date of birth. The bot then schedules a phone conversation with a human outreach worker to finish the paperwork.

As a way to communicate, text messaging is nothing new, of course: The first-ever SMS message was sent nearly three decades ago. But using texts as an entry point to government services, as Anchorage is doing, still represents something of a frontier. It’s an experiment in the idea that accessing public benefits need not be a bureaucratic nightmare, but rather, could be as simple as swapping a few messages with a friend.

“Texting is the easiest way for someone with a phone to interact with services, even if they don’t have a smartphone or a data plan,” said Brendan Babb, director of the Anchorage i-team, a group of in-house city hall innovation consultants funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies. “For people with low incomes, there’s a low barrier to entry.” The results so far back that up: After just a few weeks, more than 50 people have thumbed out SNAP requests.

Anchorage’s work builds on a wealth of public-sector experience with incorporating text messaging into communications strategies. For years, cities have used the tool to blast residents with emergency alerts, news of school closings, or changes in the trash pickup schedule. Text messages are cheap to send, and according to the Pew Research Center, 96 percent of Americans own a mobile phone, with penetration high among all demographic groups.

Anchorage is taking it a step further by testing out texting’s value in helping residents to actually access services. They’re not alone. Detroit’s i-team is experimenting with a similar system for helping families determine their eligibility for early-childhood subsidies — and to locate nearby providers. New Orleans uses text messaging to encourage eligible residents to set up free doctor’s appointments. And the Durham, N.C., i-team turned to texting to help residents clear old criminal charges in order to get their driver’s licenses back.

The work in Durham demonstrates the potential power of the approach. Previous amnesty efforts required residents to wait in line at the courthouse in order to have their records reviewed. Typically, this strategy would reach a total of only about two dozen people. But when Durham offered residents a different approach — simply texting their name and birthdate to i-team member Ryan Smith’s mobile phone — Smith’s phone blew up with messages. In just a few weeks, more than 2,500 people reached out.

“Our goal was to make it as easy as possible for people to benefit,” Smith said, recalling the flood of texts he received from residents who were eager to be able to drive legally to work or school. The Durham i-team took the messages and worked with the District Attorney’s office to confirm eligibility and then got back to people. “It took less than a minute for someone to apply,” Smith said. “Just text it in.”

In addition to helping hundreds of people regain their driving privileges, Durham’s approach was an easy, low-cost way to prove a concept. Since then, the city has worked with the courts and other partners to build a more automated program that wipes out old cases by the thousands. Individuals need not even apply to have the work done for them, Smith said, so the texting solution is no longer necessary.

[Read: Putting ex-offenders back in the driver’s seat]

But Smith still considers text messaging a useful tool for disrupting the status quo of cumbersome government application processes. One thing he’d change is that he wouldn’t use his own phone again — it clogged his inbox for weeks. Other lessons he learned: automate as much of the messaging as possible, prepare for a high volume of texts, and communicate eligibility criteria as clearly as possible. “It’s easy to end up with a lot of people applying who aren’t eligible,” Smith said. “And then you’re spending a lot of your precious staff time going through applications from people you can’t help.”

Anchorage is already putting some of those lessons to work with SNAP. The experiment grew out of the i-team’s broader body of work focused on improving food security for city residents. Although SNAP lies outside the city’s control — it’s a federal program administered by the state — the Anchorage team saw a lot of potential in encouraging more residents to apply. They estimate that somewhere around 10,000 eligible residents are passing up on monthly help with their grocery bills, leaving more than $20 million a year in federal dollars on the table.

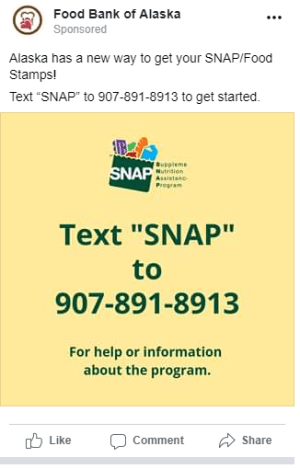

The i-team partnered with the Food Bank of Alaska, which runs a SNAP outreach program aimed at getting people signed up. Traditionally, outreach coordinators have gone to homeless shelters, food pantries, and libraries to connect with eligible residents. But they were interested in experimenting with new approaches.

“We thought texting was an exciting way to reach people,” said Cara Durr, the Food Bank’s director of public engagement. “We know from experience that we have better outcomes when we collect information from people and follow up with them, as opposed to passing out information and waiting for them to follow up with us.”

Anchorage already had some history with text-based services. The local offshoot of Code for America created a bot that texts reminders to people expected to appear in court, as well as another text-based service to tell transit users when they can expect their bus to arrive. As the i-team got talking with the Food Bank, they realized SNAP could be another good use case.

“We flipped the outreach model around to say you don’t have to go out to find people — they can come to you,” said Patrick McDonnell, the i-team’s designer. “We started calling it ‘inreach’ rather than ‘outreach.’”

[Read: Meet the new force shaking up city halls: designers]

To get the word out about the new service, the i-team spent $30 on a Facebook advertisement. It’s early yet, and Durr doesn’t yet know how many of the 50 leads generated so far will “convert” into successful SNAP applications. But she’s already seeing how the texting approach can help optimize her nonprofit’s scarce resources to reach more people. While the current test is focused on Anchorage city residents, she sees big potential in using the tool to reach rural residents in Alaska’s vast interior, where in-person outreach is difficult and expensive to do.

“It helps us refine our strategies on how we’re conducting outreach,” Durr said. “It’s an exciting tool, and we think it will be a cost effective way for us to reach new clients.”