How 13 cities are pushing themselves to innovate like never before

What happens when you put together a team of city officials who may not know much about a problem — like vacant housing or prisoner reentry — and ask them to use cutting-edge innovation techniques to come up with solutions?

This year, 13 cities from five countries are finding out. As members of the “innovation track” of the Bloomberg Harvard City Leadership Initiative, they’re engaged in one of the largest efforts ever to teach local governments to solve challenging problems using the principles of human-centered design.

These cities are flipping the script of how government usually works. Instead of jumping to solutions based on what subject-matter experts propose, they’re taking the time to deeply understand the problems facing the city by building empathy for the residents impacted by them. They’re also going out of their way to work closely with residents to come up with ideas, test prototypes, and iteratively develop programs that improve residents’ experiences and address the root causes of problems, not just the symptoms.

Each city is focusing on a particular problem selected by their mayor. For example, in Columbus, Ohio, they’re working on recruiting a more diverse police force. In Helsinki, Finland, they want to find ways to increase physical activity for people age 64 and up. And in Tulsa, Okla., they’re focused on improving the animal welfare system.

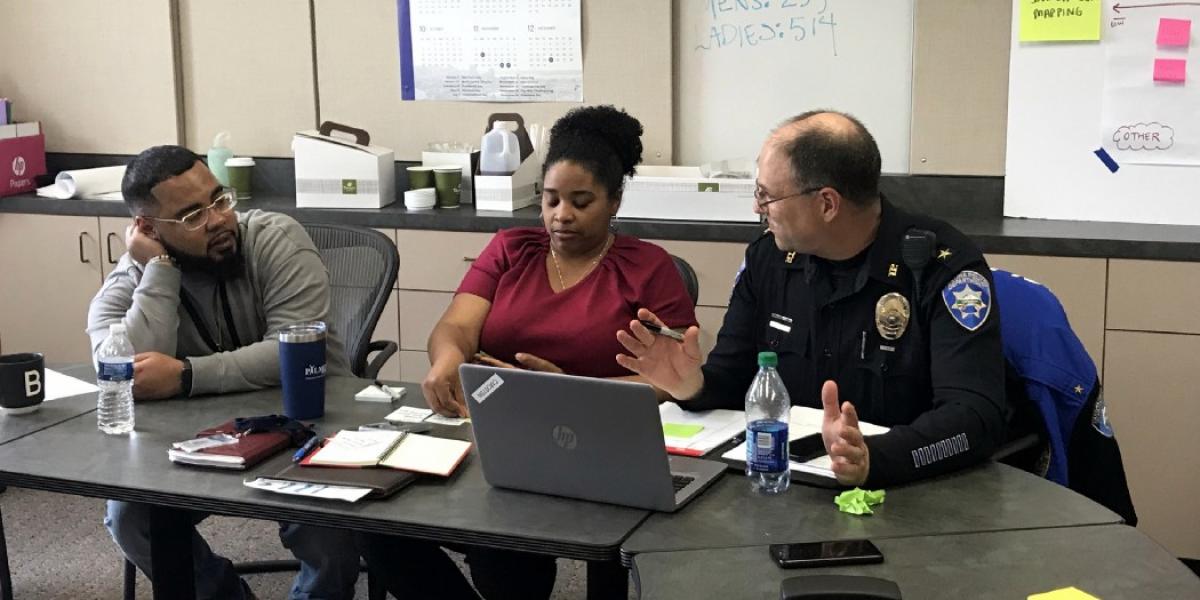

Each of them has formed a “core team” made up of staff from across city departments and partner organizations such as local nonprofits. What these groups lack in issue expertise they make up for with fresh thinking: The diversity of viewpoints is part of what breaks down government’s notorious “silos” and allows innovative ideas to bubble up. Meanwhile, design coaches on assignment with Bloomberg Philanthropies are coaching the teams on how to take human-centered design practices proven to spark innovation in the private sector and translate them to city work.

That means they’re conducting field research and interviews to deeply understand the problem they’re working on through the eyes of those impacted by it. They’re getting laser-focused on exactly what part of the problem they’re trying to solve. They’re discovering tricks for unleashing creativity when coming up with ideas for solutions. And they’re practicing building simple prototypes — like a storyboard showing the steps of how a new service might work, for example — and using them to get useful feedback from residents and a signal as to whether they’re on the right track before investing more heavily in an idea.

While the 13 city teams are still working hard on developing their ideas so they can implement them, they have already surfaced a few important lessons:

1. Be patient

For first-timers, the human-centered design process can be tough to grasp. The designer’s drive to begin with questions rather than answers is disorienting for some. The iterative nature of moving gradually toward solutions as you deeply understand the root causes of problems and rapidly test prototypes of new ideas can feel ambiguous. And the idea that it’s OK to make mistakes — embraced by designers as critical learning moments — can feel scary in risk-averse government workplaces.

[Read our explainer on human-centered design]

It all requires patience, as well as faith that the process works. To build that muscle, the team in Tacoma, Wash. — which is working on strengthening relations between police and minority communities — kicked off with an icebreaker. In 90 minutes, they applied the human-centered design process to something uncomplicated and more personal: giving a gift to someone. They emerged from the exercise with more confidence and a grasp of what to expect when applying design principles to the more fraught challenge of community policing.

2. Don’t jump to solutions

A common habit for people in local government is to try and identify solutions to problems quickly. It comes from a good place: People in public service want to help residents and get things done. What these teams learned is that it pays to dig deeper into the research on the front end. When you understand a problem in depth, you can develop ideas aimed at impacting the root causes of problems, rather than the symptoms.

[Read: Meet the new force shaking up city halls: designers]

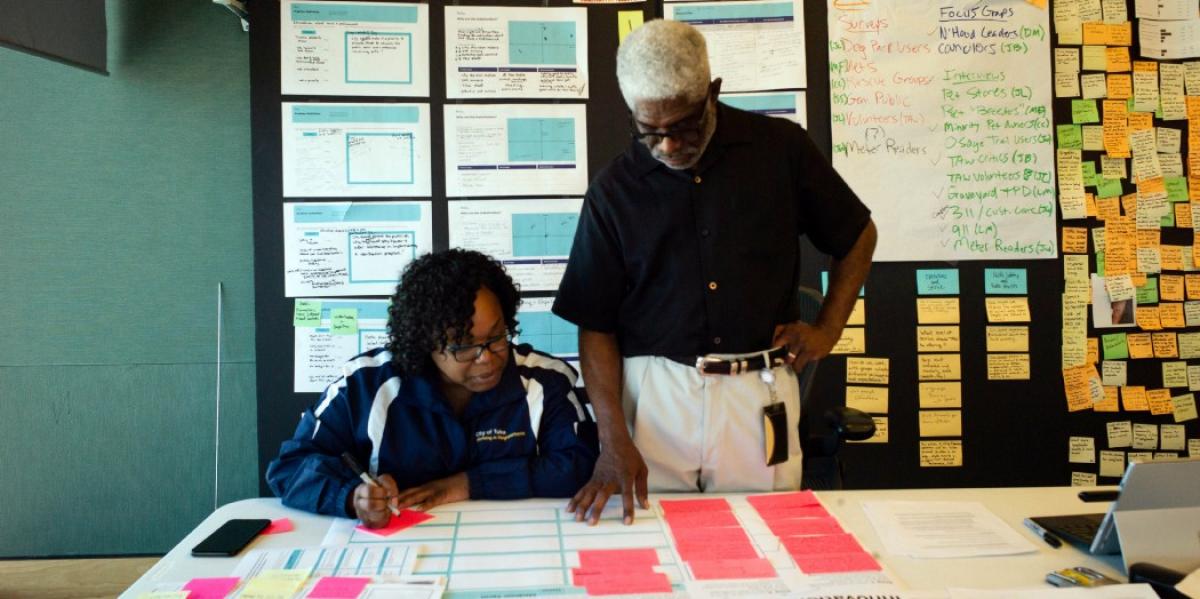

In St. Paul, Minn., the team is focused on helping people exiting the criminal justice system to find stable housing. Rather than talk to a few known experts and jump straight into solution mode, they first mapped out all the relevant stakeholders and interviewed dozens of people with criminal backgrounds, as well as landlords who do and don’t rent to them. As they turned to developing ideas, team members were grateful they’d taken the time to develop such a nuanced understanding of the situation.

3. Build empathy

You can’t solve a problem unless you truly understand it from the point of view of the people impacted by it — the humans of human-centered design. Teams practiced this by going out into the community to spend time with residents to learn what challenges look and feel like from their perspective, as opposed to what they might think it is.

[Read: How Sioux Falls is turning public problem-solving on its head]

When the Sioux Falls, S.D., core team set out to fill gaps in the city’s public transit system, they started by riding city buses and talking to passengers. Most of them had never done that before. Experiencing for themselves the hour-long trips that take 10 minutes in a car helped them internalize the problem and develop stronger solutions. Field research turned up other surprises. For example, when they interviewed residents who don’t ride the bus, they found stronger support than they expected for the idea that transit is a much needed service in the community.

4. Get feedback on ideas early

Another critical element in the human-centered design approach is to test ideas early and often, using prototypes. This saves money and reduces risk by getting feedback before investing large amounts of taxpayer dollars in a solution before you know it will work. It also helps improve an idea quickly so that by the time you’re ready to invest in it, you know it’s going to have a meaningful impact.

[Read: Prototyping city solutions and launching a revolution]

The core team’s experience in Albuquerque, N.M., is a great example. They set out to problem-solve around the issue of how to accommodate the bathroom needs of a growing homeless population. At first, the team seemed sure this would require installing expensive new public restrooms at taxpayer expense. But when they got to prototyping different ways of involving business owners, they found a willingness to help with the investment. They also found a lower-cost solution using portable toilets that met the team’s requirements for hygiene and security.

“A big revelation for me was understanding we don’t have all the answers,” said Matt Whelan, a member of the Albuquerque team. “While we might have a suggestion that we think is a good idea, you talk to stakeholders and realize it’s not right. This is about finding collective solutions.”

5. Share what you learn with others

The best way to learn something is to teach it to someone else. As these teams moved through the program, and started to see the power in this approach, they began sharing tips with colleagues so they can start using it, too.

For example, in Trenggalek, Indonesia, where the core team is working on promoting sustainable urban farming practices, they invited more than 50 city employees to their work room to show them how the design process works. Mayor Muhammad Nur Arifin wants this way of working to shape a culture of innovation within the city. “Putting residents first in the decision-making process,” he said, “is much more powerful and impactful than a top-down approach.”