Explainer: What is ‘data as a service’?

Like neighborhood business districts everywhere, London’s “high streets” are struggling. Along many of these commercial streets, sales that slowed to a trickle during the pandemic have yet to come flooding back—in large part because people have grown accustomed to buying things online rather than around the corner.

But unlike in many cities around the world, local leaders in London now have a powerful new tool to help them tackle this too-familiar problem: the High Streets Data Service. Built by the Greater London Authority, HSDS pulls together public and proprietary information, like spending data purchased from Mastercard and foot-traffic insights from telecommunications companies, to provide a granular and continuously updated view of economic activity along 600 high streets throughout the city. Local officials, who pay a subscription fee for the service that is much less expensive than if they were to secure the data themselves, now have a ready way to understand the commercial impacts of teleworking, delivery services, heatwaves, and other forces—and to share with each other what they’re learning about boosting businesses and filling vacant storefronts.

But the HSDS is more than just an economic-development tool. It’s also an example of cutting-edge thinking in city halls about how to package insights from multiple data streams in ways that are easy to put to work. This pioneering area of public-sector innovation is called “data as a service,” and it’s growing in cities around the world. In our latest explainer, Bloomberg Cities answers the following questions about this work:

- What is data as a service?

- What are the benefits of this approach?

- What challenges are cities facing, and how are they navigating them?

- How can other cities get started?

What is data as a service?

In a world with more data than ever—much of it collected by cities—data as a service is an emerging method of curating and analyzing multiple data streams in ways that cast new light on problems, enabling solution-seekers in or out of government to gain insight and craft new interventions.

A good way to understand data as a service is that it’s an evolution of the “open data” movement. Over the past decade, local governments around the world made significant inroads in publishing more timely and accurate public data online—often in hopes that researchers, civic hackers, or others would turn that data into useful products and meaningful insights. More often than not, however, these public datasets were difficult to penetrate, attracted little notice, and didn’t spur much action.

Data as a service aims to make the search for useful insights in this data easier, through identifying and assembling the data needed to answer specific questions. “It’s moving from a passive approach to city data to one that is much more active,” explains Theo Blackwell, London’s Chief Data Officer. It’s about unlocking more value by pairing open data with other public or private datasets in order to empower purposeful products and services, he adds.

Another problem London has tackled in this way is the lack of coordination between utilities and others who dig up city streets to repair or replace underground pipes and wires. A service called the Infrastructure Mapping Application now aggregates data from utilities, telecommunications companies, and local authorities about where their underground infrastructure lies and when they plan to replace it. The various parties use it to coordinate construction and, whenever possible, dig only once. The city estimates that collaborating in this way has saved Londoners at least 794 days of road work disruption over the past few years.

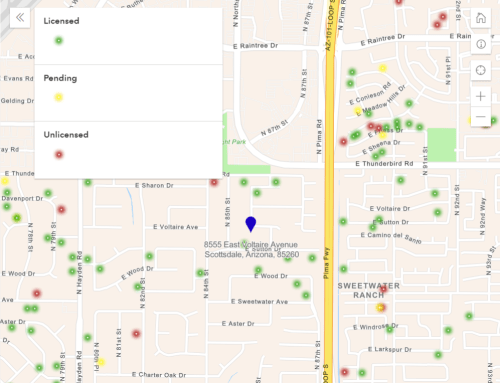

Scottsdale, Ariz., took a similar approach to address resident complaints about short-term rentals. As part of its participation in the Bloomberg Philanthropies City Data Alliance, the city launched a tracking map that blends its license data with privately collected data, scraped from the websites of companies such as Airbnb and Vrbo, to show where short-term properties are located and whether they’re being operated legally. City inspectors use the map to target their enforcement efforts, while residents use it to better understand how these properties are impacting their neighborhoods.

What are the benefits of this approach?

Data as a service is all about using data to solve problems. And it’s very intentional about understanding the users of that data and what their needs are, whether those users are local leaders themselves or businesses, nonprofits, academics, residents, or others outside city hall.

“The critical question is, who could do what differently if they had access to better information?” explains Eddie Copeland, Director of the London Office of Technology & Innovation, or LOTI. Data as a service is a way for city leaders to “get a grip on the data you’ve got, join it up, and act on it,” he adds.

One data service LOTI is helping to build along with numerous partners, including Bloomberg Associates, is aimed at tackling homelessness. The idea is to bring together datasets from across the ecosystem of homeless-service providers in order to give decision makers a clearer and more granular view of the problem and potential interventions than ever before.

“All of this data is going to be brought together for the first time,” says Jay Saggar, a program manager at LOTI. “And then we can use that information to either respond to needs or plan proactively for the types of services we might want to design for the future.”

What challenges are cities facing, and how are they navigating them?

Moving toward a data-as-a-service approach can pose a number of challenges to city leaders, including around collaboration, ethics, and the sustainability of these new efforts.

The need to collaborate can be both a challenge and an opportunity. That’s certainly the case in London, where local services are delivered by 33 local councils, among other players. “London is a 33-piece jigsaw puzzle where the pieces were never put together,” says Copeland, who adds that “pollution, climate change, pandemics, and homelessness transcend borough boundaries.”

To facilitate better collaboration, LOTI is now focused on streamlining the agreements boroughs use to standardize how they’re collecting and sharing data with each other. Without this effort, Copeland says, developing citywide data services like the ones focused on homelessness, infrastructure, and high street economies would be impossible.

Any data use comes with questions around how to do it responsibly. And data as a service is no exception, especially when private or proprietary data come into play. While the upsides of this approach can be huge, using data from third parties comes with heightened considerations around privacy, equity, and transparency. Likewise, bias can be a factor in decisions to prioritize serving one use case over another. In London, LOTI has hired a data ethicist to help local boroughs navigate these and other thorny issues.

Ensuring the sustainability of these efforts can be another concern. Data services typically aren’t one-and-done projects. To remain useful, they need to be continually updated, iterated upon, and assessed. While there’s a case to be made that cities will need more data scientists, Amanda Smith, a Director at the London-based consultancy Public Digital—a Bloomberg Philanthropies partner in spreading this work in cities—says the bigger need is in building data skills and literacy at all levels in city hall.

“You want to be sure that you’ve got good, repeatable processes in data, in digital, in technology, so that you can keep scaling up and reducing the cost over time,” she says. “But you’ve got to also complement that with a broader data culture. Otherwise, you’re going to keep creating that same bottleneck of having only two people on the data team who can do the work.”

How can other cities get started?

Cities looking to take this work to the next level should first consider creating a “data service standard.” Essentially, that is a set of principles defining how they’ll use data to solve problems and build data services—and do that over and over again for different kinds of problems using different kinds of data.

Last year, Arlington, Texas, became the first U.S. city to pass a data-service standard. One core principle of Arlington’s standard is to “publish data with a purpose,” meaning that data services must be vetted to make sure they address critical community issues. Other principles include working in multidisciplinary teams, understanding users and their data needs, and making information accessible by all users, regardless of their abilities or type of device.

Scottsdale also passed its own data service standard in March. London is working on finalizing one soon. Having a public-facing standard for implementing high-quality data and analytics services is now part of the criteria for cities who hope to achieve What Works Cities Certification as one of the best at using data.

Amanda Smith recommends that after drafting a standard, cities pilot a data service to see how it works in practice. “At the heart of a really good data-service approach,” she says, “is starting small and finding that exemplar beacon project where you can understand your process by doing things, seeing what the reality is on the ground in terms of how you’re working, how you engage your users, and explore your ways of working.”

A good place to start is with data from 311 or other public-feedback platforms. “If a city wants to get started on this tomorrow, start by looking at what your residents are complaining about,” Smith says. “That is a massive area of untapped value that you could be releasing as a data service to preempt questions, build trust, and improve working relationships between cities and communities.”