Data watch: Why we need better data to tackle vaccine inequities

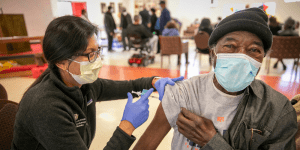

A man in Denver, Colo., receives his second COVID-19 vaccine shot. (AP Photos/Hart Van Denburg)

It’s happening again.

Black and Brown people in America are being left behind in the fight against COVID-19—and this time, in the countrywide push to vaccinate as many Americans as quickly as possible. The data are fuzzy and incomplete, with the CDC reporting demographic detail for only about half of all those vaccinated. Yet, even with this limited information, our Bloomberg Cities analysis shows that in cities across the U.S.—and even in those cities where leaders are putting significant focus on equity—White residents are getting vaccinated at far higher rates than Black, Latinx, and Hispanic residents.

The parallels—between this data and what we saw just a year ago at the outset of the crisis—are especially troubling. Then, it was emergency workers and hospital staff who were sounding the alarm about the disproportionate toll COVID-19 was taking on Black and Brown communities, even though none of that showed up initially in testing data because granular demographic information was, for the most part, not being collected. In fact, we are still waiting for some states to share demographic data on testing and those who have access to it. We had most of a year to anticipate and prevent similar patterns of missing data and inequity arising with vaccinations. Apparently, we did not learn from our mistakes.

When you look at the demographic data on vaccinations, you can’t explain away the inequities we’re seeing as simply “vaccine hesitancy” among people of color: Polls are not showing wide gaps in vaccine hesitancy among Black, Hispanic, and White respondents. What we’re seeing in the data is more a reflection of the deep disparities in our public health infrastructure. It’s showing us that limited vaccine supply is not being targeted to the communities that need it most. And it’s telling us that more White people are able to spend hours online to snag coveted appointments. If you don’t have the internet at home or don’t have the time because you’re working multiple jobs, the systems we’ve set up to get people vaccinated simply will not work.

[Get all of our vaccine resources for mayors here]

To fix this, we need better data. All of the data we have access to is voluntarily reported and collected by shoestring operations in state and local governments who struggle to keep up. For every state that has put serious effort into building up their data infrastructure during the pandemic, there’s another who hasn’t. This is one place where we need more guidance from the federal government—and requirements to collect detailed data in return for vaccine supplies and aid for distributing them. Early signals from the Biden Administration point to a deep appreciation for these disparities, with emergency funding soon to land in state coffers, but there is still significant work to be done to get all those who want to be vaccinated the access they need. Most importantly, we must insist that investments made in closing the vaccination gaps extend to getting more access to testing for priority populations, and that this moment becomes a catalyst for widespread public health reform.

For their part, city leaders can do three things as the data becomes clearer about where in their communities the vaccination gaps lie. First, they can use this data to target outreach and resources like mobile vaccination clinics. Second, they can use the data to advocate with county and state partners to locate more clinics in Black and Brown communities and reserve appointments for people coming from the hardest-hit ZIP codes. And they need to start thinking about the long-term. Inequitable access to vaccines is just the latest example of how some populations in America are essentially cut off from the public health system. We need to use this moment to redesign public health for the people who need it most.

Beth Blauer is the Executive Director of the Centers for Civic Impact at Johns Hopkins University