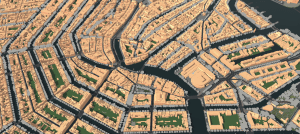

Amsterdam shows where ‘digital urban planning’ is headed

With cutting-edge initiatives on smart mobility, reducing waste, artificial intelligence, and more, Amsterdam City Hall has a worldwide reputation as a leader in public-sector innovation.

That’s why the Bloomberg CityLab summit will be held in Amsterdam next week. It’s the perfect place for global mayors, city innovators, business leaders, urban experts, artists, and activists to learn, share, and be inspired to find new ways of tackling their cities’ toughest challenges.

Amsterdam also is known as a city on the digital frontier. In fact, the city employs staffers whose primary responsibility is to spot new technologies that will impact the city and create opportunities to serve residents in new ways. A big focus is creating new opportunities for residents to participate in decision making, while also protecting their digital rights. Another is uncovering new ways to protect vulnerable residents. For example, a city collaboration with the group World Enabled uses AI to scan Google Street View images to identify accessibility barriers such as broken sidewalks that need fixing.

Among the people leading the digital charge in Amsterdam’s City Hall is Bruno Ávila Eça de Matos. With a background in technology and urban design, Ávila believes he’s the first city official in the world to hold the title “digital urban planner.” He’s also the head of the city’s new digital innovation team, one of six such i-teams recently funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies.

Being a digital urban planner, Ávila says, means taking increasingly common tools like 3D modeling and advanced geographic information systems and finding new ways to engage residents with them. “Being in this role is, for me, an honor and also a challenge,” he says. “Giving shape to this new function requires reimagining the way urban planning and urban design can benefit from technology.”

To start, Ávila and the i-team are focusing their efforts on a neighborhood called Zuidoost. It’s one of Amsterdam’s largest and most diverse areas. There’s also higher poverty rates and less economic opportunity than in other parts of Amsterdam. About two-thirds of the 90,000 residents are migrants, and 35 percent of the population is under the age of 35.

Over a three-year period, the i-team will partner with other stakeholders to improve housing, public space, and digital infrastructure in Zuidoost. Promoting the use of digital tools in urban planning is their first priority, addressing issues like equality in the housing market. Housing prices are skyrocketing across Amsterdam. And while Zuidoost has the city’s highest concentration of rent-controlled social housing, the population is expected to increase by 38 percent in coming years, putting more and more pressure on housing availability and prices.

Ávila says he and his team are taking a three-pronged approach at tackling these challenges. First, they’re doubling down on using human-centered design, an innovation approach that has city leaders researching, designing, and prototyping solutions side-by-side with residents. This keeps the team focused on solving problems that matter to residents and not just chasing flashy technology for its own sake. “We have the time to really find the specific need of the residents before we propose a technical solution,” Ávila says.

One idea they’re exploring—the creation of a “digital twin” or virtual replica of the neighborhood—could be used to help residents envision change before it happens, strengthening their hand to participate meaningfully in the development process.

“There are a lot of possibilities for a digital twin,” Ávila says. “It can make it easier for citizens to contribute to discussions and to participate in processes with the same information the government has.”

The i-team’s second focus is to find new ways to better engage other stakeholders. Ávila uses a cross-sectoral collaboration framework common in Amsterdam—the “quadruple helix”—which leverages the unique expertise of government, universities, the private sector, and residents to solve problems. “We believe that a nice innovation ecosystem brings these groups of stakeholders together,” he says.

Third, i-team members bring different skills and orientations to the work. In addition to Ávila, Amsterdam’s i-team includes profesionals with knowledge in data science, service design, and urban innovation; additional support on communications and software development comes through the city’s Innovation Department. The team’s diversity, and holding space for them to think differently, is part of what will help new ideas flow, Ávila says.

“Something I'm learning is how to create a protected ecosystem that fosters innovation in our team,” Ávila says. “We need to take risks, and within a municipality it can be difficult to do that. So we need to create this space where we feel safe to share ideas and that all ideas are welcome.”