6 city innovations that are powering the rollout of electric vehicles

Vehicles that run on electricity instead of gasoline have a big role to play in the push to curb climate change. But it’s clear that there’s a lot of work to be done — especially when you realize that electric vehicles, or EVs, currently make up only 2 percent of the cars sold in the United States.

Local governments are perfectly positioned to effect change — whether that’s by encouraging residents to buy EVs, by building out the necessary charging infrastructure, or by purchasing EVs for their own fleets. However, they face strong headwinds, especially when it comes to cost: EVs can be less expensive than gasoline-powered vehicles to operate, but they can cost more to purchase.

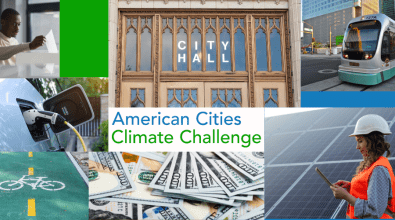

A growing number of local governments are overcoming these barriers, thanks in part to a boost from the American Cities Climate Challenge, a Bloomberg Philanthropies initiative accelerating climate action in 25 U.S. cities. They’re bringing innovation tools such as data analysis, experimentation, and resident engagement to bear in the search for solutions, and sharing peer-to-peer what they’re learning.

As cities across the country this week celebrate their progress under the banner of National Drive Electric Week, here are six ways city leaders are innovating and demonstrating leadership in the push to get more EVs on the road.

1. Pooling procurement

A growing number of cities have committed to electrifying their municipal fleets, which in big cities can run well into the thousands of vehicles. However, it’s not easy for cities to buy or lease electric vehicles, in terms of how government purchasing usually works.

That’s because many states have not yet added EVs to the menu of products they’ve negotiated prices for. So cities, who often piggyback on these state contracts, are on their own for a procurement process that can take many months. What’s more, leasing vehicles — a potentially attractive option for EVs — is almost unheard of at the local level.

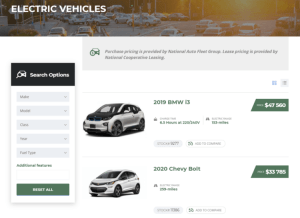

More than 150 cities are getting around this by pooling their purchasing power through what’s known as the Climate Mayors EV Purchasing Collaborative.

The collaborative negotiates lower prices on both EVs and charging stations than most cities could get on their own. It’s also making it easy for cities to give alternatives like leasing EVs a try. That’s critical, as it provides a pathway to access savings from federal and state tax credits that cities, as government entities, would not otherwise be able to claim. (The leasing is similar to what consumers do but there are special “municipal leases” that give cities a path to owning the vehicle, too.)

Participating cities have committed to procuring more than 2,300 light-duty EVs through the collaborative by next year.

“Transitioning city fleets is important to meeting cities’ goals around reducing their carbon footprint, reducing dependence on oil, and improving resilience,” said Ben Prochazka, vice president of the Electrification Coalition, one of the partners behind the collaborative. “But it’s also normalizing EVs for consumers to be seeing those branded city vehicles driving down the streets every day.”

2. Re-thinking city budgets

Another hurdle for EVs is the way cities typically budget for big-ticket items. Typically, costs associated with vehicles show up in two different places. The vehicle itself comes out of the capital budget. Fuel and maintenance costs come out of a separate operating budget.

This gets tricky with EVs because they might cost more upfront than gas-powered models — and the lowest price option usually wins. However, the operating costs of EVs are significantly lower because electricity generally costs less than gasoline and they require less maintenance. City budgeting practices aren’t usually nimble enough to consider both sides of this equation.

It’s not impossible, though, as Cincinnati is showing. The city has figured out how to bridge its capital and operating budgets in a way that takes the total cost of ownership of EVs into account. The math is based on a detailed fleet assessment allowing the city to identify where EVs will provide the best return on investment. Thanks to this re-think, Cincinnati is able to ramp up its EV fleet from three this year to an expected 20 next year.

“By merging those budgets and thinking about the total cost of ownership, cities are more likely to be able to make a strong case for EVs,” said the Electrification Coalition’s Matt Stephens-Rich, an adviser to the Cincinnati effort. “These are often the most boring conversations you can have but they’re absolutely where the rubber meets the road when buying an EV.”

3. Sharing electric vehicles

It’s a common sight outside city halls and other places where municipal employees work: fleet vehicles sitting unused in the parking lot. Jersey City, N.J., doesn’t want to see that happen with its first batch of four EVs, which just arrived a couple of weeks ago.

That’s why the city is testing a carshare plan aimed at ensuring those cars are constantly on the go. Employees will use a software program to reserve the vehicles and a keycard to unlock them. For now, the system also includes gasoline-powered vehicles, but as the city procures more EVs the plan is to transition the carshare program to all-electric.

“Historically, what a lot of cities do is assign individual vehicles to specific employees — so the director of some department gets a vehicle, but it often sits idle in the parking lot,” said Brian Platt, Jersey City’s city manager and business administrator. “What we’re doing is reducing the number of vehicles we need and better optimizing the use of the vehicles we have.”

There’s another benefit to this strategy. With electric vehicles, the more you use them, the faster the payback in terms of reduced fuel and maintenance costs.

4. Building out charging infrastructure

Cities have a number of tools they can use to speed up the rollout of the charging infrastructure that EV users rely on.

For example, St. Paul, Minn., is teaming with Minneapolis on a plan to build out 70 EV charging hubs with public charging and 150 carsharing vehicles to be operated in both cities. In the future, some of these charging hubs may be incorporated into broader “mobility hubs” with additional transportation connections and options. Jersey City has installed charging stations near city hall for its fleet vehicles and allows the public to use some of them. The city is also following the lead of cities like New Orleans and Seattle by clearing the way for sidewalk charging installations for residents who don’t have garages or driveways.

[Read: How innovation can fuel the fight against climate change]

“We don’t have a huge number of EV owners in the city now,” Platt said, “but seeing EV charging stations every day helps make the possibility of buying an EV more real for residents.”

Cities also can influence outcomes with private construction through their building codes. Atlanta, for example, passed an “EV ready” ordinance into law in 2017 requiring new residential homes and parking structures be wired to accommodate EV charging stations when needed.

5. Turning EV driving into a perk

For consumers, rental cars influence buying decisions. Love a car you rent while on vacation or traveling for work, and it may convince you to buy that model the next time you’re in the market for one.

Orlando, Fla., sees the opportunity in this. With more than 75 million visitors last year, the city is the world’s largest rental-car market. City leaders have not only partnered with rental-car agencies to make EVs available at the airport, but have turned the cars into a “VIP pass” that earns drivers perks like free valet parking at hotels and prime parking spots at the front gate of theme parks.

“We’re the test-ride city of America,” said Orlando Sustainability Director Chris Castro, noting that the Orlando area already has a robust and growing network of 400 EV charging stations. “Our goal is to leverage tourism here in Central Florida to be a catalyst for people to experience electric vehicles.” Soon, project partners will be publishing a white paper laying out the results of this experiment and steps for other cities to replicate it.

One challenge, Castro said, is that EVs don’t always fit the business model of big rental-car companies, who tend to buy cars by the thousands and re-sell them quickly on the secondary market. Orlando is studying whether the city and other big organizations could play a role in purchasing those used EVs, at a used-car discount, as part of their own efforts to electrify their fleets.

6. Engaging the public

Cities aren’t just buying EVs for their fleets. They’re also working to educate and inspire residents to consider buying the vehicles themselves.

A good example is Charlotte, N.C., which today is hosting a downtown street party as part of National Drive Electric Week. More than a dozen EVs will be on hand, giving curious residents a chance to check out the vehicles and learn how they work. “We have people from the community who wanted to bring their own vehicles and are excited to talk to others about why they switched,” said Erika Ruane, Charlotte’s sustainability coordinator. “Nobody sells an EV better than an EV owner.”

Charlotte has run similar events before, but this year’s will be much bigger, with a band playing and a prominent downtown street shut down to pull in foot traffic. Organizers also are using it as an opportunity to survey residents about what they need to make the switch to electric — data city leaders can use to inform their current EV efforts and track over time in future surveys to see how they’re doing.