5 steps to conduct COVID-19 scenario planning in cities

These are times of great uncertainty for local leaders. The questions for the future are big, complex, and existential. Will COVID-19 be under control relatively soon or still be a serious problem a couple of years from now? Will the economy bounce back quickly, or are we entering a prolonged depression? Will people be willing to ride transit again, or eat out, fly on airplanes, or stay in hotels?

For mayors and their teams, these questions are confounding. It’s not just because there are no easy answers. It’s also because reasonable people can look at any of today’s mega-problems and draw opposite conclusions. “So many people are trying to find what the future will be,” said Harvard Business School Professor Rebecca Henderson, “and you can get into horrible arguments. Like: ‘We’ll have COVID under control in a moment, it’s not a big deal.’ ‘Yes it is.’ ‘No it isn’t.’ That’s not a helpful conversation.”

To help navigate this uncertainty, Henderson recently led hundreds of mayors and senior city staff in an exercise in scenario planning. The session was a key focus of last week’s online coaching and learning session of the COVID-19 Local Response Initiative. Scenario planning, Henderson said, can help city leaders bring structure to confusing moments like this one, and give teams a way to prepare for several possible futures.

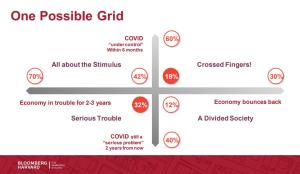

Henderson introduced a simple five-step tool that city teams can use to facilitate scenario-planning conversations. She also left them a hypothetical example (pictured here) of how this exercise might play out based on real questions cities are facing today. The steps are below:

1: Make a list of key uncertainties. At a time when so many things seem up in the air, the first step in scenario planning is to sort out what those things actually are. Make a list of all the big questions — not things you have control over, but things that reflect wider uncertainty about what sort of world is coming. One way to think about it, Henderson said, is to imagine you have a chance to ask a visitor from the future how things turned out. “What would you ask?” Henderson said. “What do you really need to know in order to make decisions?”

2: Choose two of them. The next step is to narrow things down. Look at the whole list of questions and choose two. They must be uncertainties that have a genuine chance at becoming real — and would deeply impact decision-making if they did. There’s no use using this exercise with uncertainties that have almost no chance of happening, or almost certainly will, Henderson said. “There should be about a 50–50 chance of it happening.”

In her hypothetical example, one uncertainty had to do with how long COVID-19 would remain a problem, and the other was how long the economy would remain in trouble.

3: Draw a “map” of those two uncertainties. To visualize these uncertainties, the next step is to sketch them out in a two-by-two diagram. Plot one of the uncertainties along the X axis, and the other along the Y axis.

In Henderson’s example, the economy went along the X axis, with “the economy bounces back” on one side, and “the economy stays in trouble for two to three years” on the other. COVID went along the Y axis, with the disease “under control within six months” on one side and “still a serious problem two years from now” on the other.

4: Give your four “possible futures” a name. Once the uncertainties are mapped, four separate futures come into view, one in each quadrant. Give each of those scenarios a name. The name should embody what sort of world that future would look like for your city — and start to make real what sorts of decisions might be necessary should it come to pass.

In the hypothetical example, Henderson called the scenario everyone is hoping for “Crossed Fingers.” That’s the one where the economy bounces back quickly and COVID-19 is under control before long. On the opposite side of the diagram is “Serious Trouble.” That’s where COVID-19 causes long-term disruption and the economy tanks for years.

5: Think about the odds. Finally, consider the chances of each of those scenarios coming true. Start with each uncertainty, and assign each side a percentage — what do you think the odds are that COVID comes under control soon, versus lingering a while? Then multiply the two numbers for each quadrant to get a rough percentage chance for each of the four scenarios coming to pass.

This is where reality checks often happen, Henderson said. Optimists may be disappointed to find here that what most would see as the best-case scenario isn’t the most likely one. But this is also where tough conversations and serious planning can begin.

“If you’re having trouble persuading your team that the future might look really different, this analysis is really, really helpful,” Henderson said. “I’ve used it with energy firms telling me that renewable energy is never going to come, forget about it. I’ve used it with food firms telling me that people will never care about organic, go away. What it does is give the whole team a chance to think about what the future is going to look like. What do we want to prepare for?”

Henderson recommends playing out this exercise multiple times, experimenting with new uncertainties in different combinations. The point of the exercise to spark focused conversations.

“In the end, you’re not trying to get the right answer,” Henderson said. “You’re trying to get people to realize that there is no single future, and you need to make plans that you may or may not need. That’s the goal of this.”

(Photo: Shutterstock )